Exploring superconducting electrons in twisted graphene

Could up the game of lossless power transmission, levitating trains, quantum computing, even energy-efficient detectors for space exploration

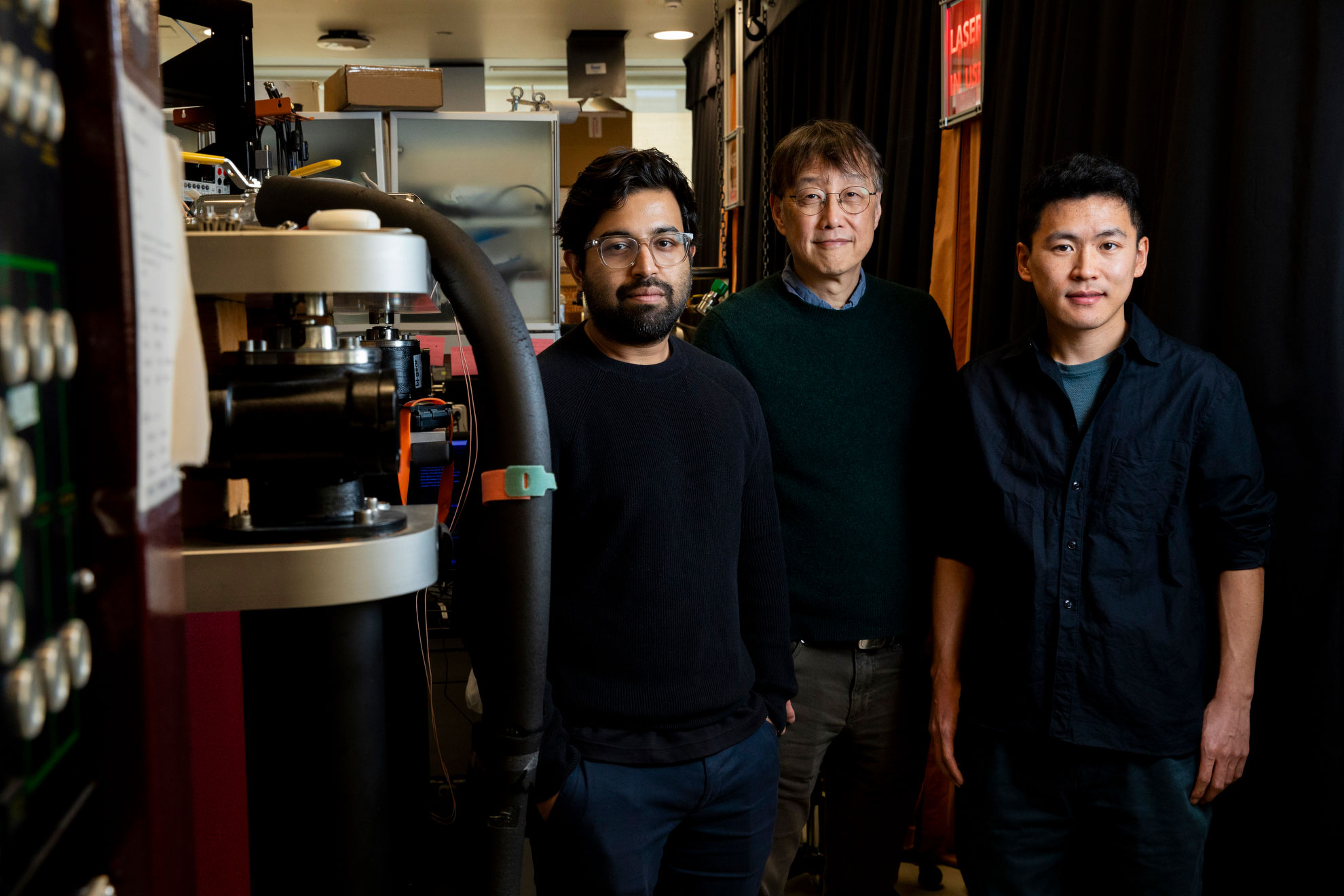

Abhishek Banerjee (from left), Philip Kim, and Zeyu Hao.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Superconductors, materials that can transmit electricity without resistance, have fascinated physicists for over a century. First discovered in 1911 by Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who observed the phenomenon in solid mercury cooled with liquid helium to around minus 450 F (just a few degrees above absolute zero), superconductors have been sought to revolutionize lossless power transmission, levitating trains, and even quantum computing.

Now, using specially developed microwave technology, a team of researchers from Harvard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Raytheon-BBN Technologies has revealed unusual superconducting behavior in twisted stacks of graphene, a single atomic layer of carbon. Their research was published in Nature.

Graphene was discovered in 2004 by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, earning them the Nobel Prize in physics a few years later. In 2018, an MIT team led by Professor Pablo Jarillo-Herrero, one of the authors of the new paper, discovered superconductivity in a stack of twisted bilayer graphene.

“This seminal work showed that a small twist between two layers of graphene can create drastically different properties than just a single layer, and since then, scientists have also found that adding more layers of graphene with a small twist can lead to similar superconducting behavior,” said Zeyu Hao, a Ph.D. student in the Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences working in the Kim Group lab at Harvard and one of the paper’s co-lead authors. The researchers’ most striking finding is that the superconducting behavior of electrons in twisted stacks of graphene differs from conventional superconductors such as aluminum. That difference “calls for careful studies of how these electrons move in sync — this ‘quantum dance’ — at very low temperatures,” Hao said.

Understanding why electrons pair up instead of repelling each other, as they naturally do due to their negative charge, is the key to uncovering how superconductivity arises. “Once electrons pair strongly enough, they condense into a superfluid that flows without losing energy,” said Abhishek Banerjee, co-lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow in the Kim group. “In twisted graphene, electrons slow down, and the interaction between them somehow mixes with quantum mechanics in a bizarre way to create a ‘glue’ force that binds them in pairs. We still don’t fully understand how this pairing works in this new class of superconductors, which is why we’re developing new ways to probe it.”

One such approach is to measure the resonant vibration of the superconducting electrons — a “superfluid” of paired electrons — by illuminating them with microwaves, which is a bit like “listening to the tune” of the superfluid, said Mary Kreidel, co-lead author of the paper who worked with Mallinckrodt Professor of Applied Physics and of Physics Robert Westervelt at Harvard and Kin Chung Fong at Raytheon BBN Technology.

“It’s similar to playing a glass harp,” said Hao. “Instead of blowing over bottles filled with varying amounts of water to produce different notes, we use a microwave circuit as the ‘bottle,’ and the ‘water’ is the superfluid of paired electrons. When the amount of superfluid changes, the resonant frequency shifts accordingly. Essentially, we’ve made our glass bottles using this microwave resonant circuit, and the water is basically the electrons paired up to condense into a superfluid, where the electrons can flow without losing energy.”

“When the weight and volume of the superfluid — essentially the density of paired electrons—changes, so does the musical tone,” said Kreidel.

From these frequency shifts, the team observed unexpected clues about how these electrons might be pairing up. “We learned that the adhesive force between electrons can be strong in some directions and vanish in others,” said Ph.D. student Patrick Ledwith, who works at Harvard with George Vasmer Leverett Professor of Physics Ashvin Vishwanath. This directionality resembles what’s seen in high-temperature superconductors made from oxide materials — still a puzzle to scientists, even after 40 years of study. “Perhaps our findings with twisted graphene can shed light on how electrons perform this quantum dance in other two-dimensional superconducting materials,” said Professor of Physics and Applied Physics Philip Kim, the lead scientist on this work.

While graphene technologies can’t yet be mass-produced, the researchers see wide-ranging potential. Kreidel, now a postdoc at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, points out that such materials could help build ultrasensitive, energy-efficient detectors for space exploration. “In the near vacuum of space, there’s very little light,” she said. “We want small, lightweight detectors that use minimal power but have extremely high resolution. Twisted graphene may be a promising candidate.”

This project was supported, in part, by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.