Illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

U.S. students need to start showing up

Detailing latest recovery scorecard, Ed School researcher urges broader action to reduce absenteeism and a sharper focus on targeted catch-up efforts

For the latest report from the Education Recovery Scorecard, co-authored by Harvard’s Thomas Kane and released Tuesday, researchers compared academic recovery in math and reading for individual school districts enrolling 35 million students in 43 states. Among the findings: Students are moving in the “wrong direction” in reading; tutoring seems to reward investment; and chronic absenteeism continues to be a drag on student performance.

The report — a collaboration among the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard, the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, and faculty at Dartmouth College — comes months after the expiration of federal relief funding for K-12 schools. Federal aid of approximately $190 billion was distributed to schools, which had until September to use the money.

In this edited interview with the Gazette, Kane, director of the Center for Education Policy Research and a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, details both the latest results and the launch of a Harvard-led initiative to help states identify and share evidence-based policies to reduce chronic absenteeism and to improve reading and math skills.

You’re now in the third year of producing the scorecard. How would you describe the student recovery story at this point?

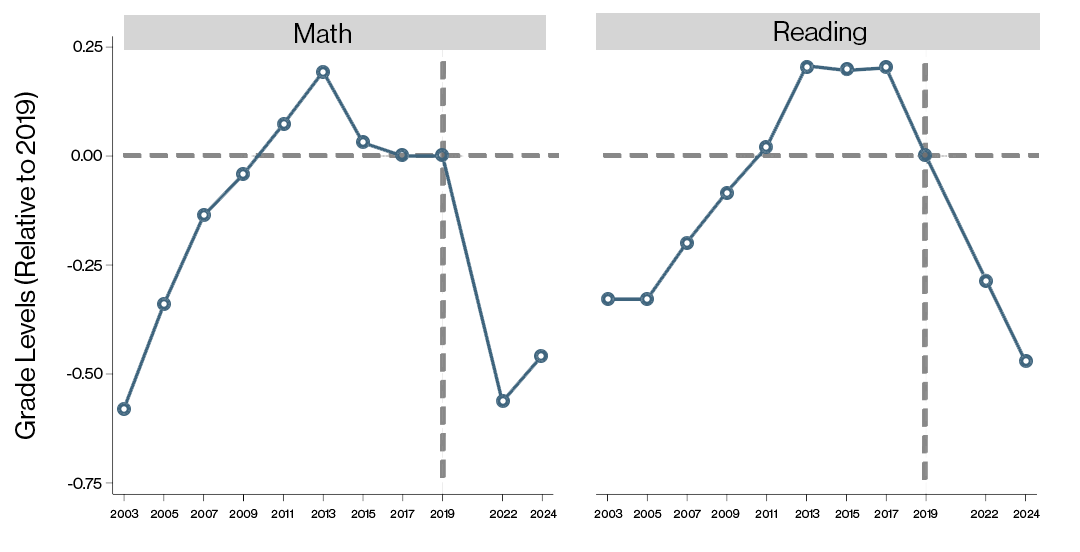

Students have continued to recover slowly in math, although the average student is still almost half a grade level behind. In reading, rather than recovering, students are going in the wrong direction, losing more ground between 2022 and 2024. The loss in literacy came despite initiatives to implement the “science of reading” in many states, including Massachusetts.

Literacy levels were declining even before the pandemic, correct?

There has been a slow decline since 2015, especially among those with weak reading skills. Not all of the losses that we’re seeing are due to what happened, or didn’t happen, with in-person or remote instruction during 2020 and 2021. Some of it has been due to trends that started before the pandemic.

National test scores (Grades 3-8, 2003-2024)

But some of it has been due to trends that started with the pandemic. For example, if the pandemic was an earthquake, the subsequent rise in absenteeism has been a tsunami that is continuing to disrupt learning.

There are areas of success that you point to in some higher poverty districts, including Compton, California, and Ector County in Texas. What has been the difference-maker?

It’s too early to say which strategies worked generally, but we can see the districts that recovered and we’re beginning to learn what they did. For instance, in Ector County, which includes Odessa, the district shifted to outcomes-based contracts for tutors. Tutoring contractors didn’t receive full payment unless students reached targets in terms of attendance and improvements in math and reading scores. Other places like Birmingham, Alabama, hired math coaches that helped teachers improve math achievement. So, there wasn’t one strategy that successful districts used. The most generalizable evidence of efficacy has been for high-dosage tutoring and summer learning.

The story seems to be that changes happened not so much at the state level, but from district to district. Can you explain the level of variation in test scores?

Ninety percent of the federal pandemic relief went directly to school districts. The federal Department of Education and state departments of education were given very little authority to coordinate efforts or encourage districts to spend the dollars in one way or another. This was an extreme example of devolution, of handing the money directly to local districts to decide. Some districts were more successful than others in helping students catch up.

Was the federal relief money effective?

Among districts with similar poverty rates and other characteristics, those receiving more federal funding caught up faster. The impact per dollar was about what prior research suggested you would get from a general revenue increase. It really depended on how districts spent the money. In California, where we had more details on spending, we saw that districts that spent more on academic interventions, such as tutoring and summer learning, as opposed to across-the-board salary increases, saw faster catchup.

The diluted impact of the pandemic relief on academic recovery was a result of the American Rescue Plan law; it granted tremendous flexibility to local communities to decide how to spend the money. They were only required to spend 20 percent on academic recovery. Some focused more on academic recovery than others.

The report shows increases in socioeconomic and racial disparities in math and, to a lesser extent, reading achievement. Can you talk more about that trend?

Horace Mann famously described public schools as “the balance wheel of the social machinery.” We definitely saw that in effect during the pandemic. When schools closed, losses were larger in higher-poverty districts. That has continued as chronic absenteeism has risen around the country. Although absenteeism has increased in most districts, it has grown more in higher-poverty schools. Each day missed is going to be more costly for students in higher-poverty districts.

“If the pandemic was an earthquake, the subsequent rise in absenteeism has been a tsunami that is continuing to disrupt learning.”

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Now that all the federal relief dollars have been spent, the focus of your work appears to be shifting from short-term recovery efforts to longer-term reform. What should the priorities be for states and districts moving forward?

We’re trying to shift the conversation away from debating how the federal money was being used or misused toward deciding what must be done now. The top priority must be identifying funds to continue targeted academic catch-up efforts, like tutoring and summer learning. For instance, states are allowed to set aside 3 percent of federal Title I dollars for direct student services like tutoring. Currently, only one state exercises that authority — Ohio.

Second, we need a broad-based effort to lower absenteeism. Until now, we’ve left the responsibility for recovery entirely on the shoulders of principals, superintendents, and teachers. But lowering absenteeism is one of the few things that community leaders outside of schools could be helping with now. That could be through public information campaigns or through science museums supporting extracurricular activities at school to make school more attractive for students. Employers could be asking their employees if they need flexibility for school pick-up and drop-off activities.

A third thing is to ask teachers to inform parents when their child is below grade level. From the very beginning of the recovery, polls have shown that parents underestimate the impact of the pandemic on their child’s learning. Teachers know kids are behind, but it hasn’t affected the grades they give. If parents continue to think their own children are fine, they aren’t going to sign up for summer learning, they’re not going to be as concerned about absenteeism, and they may resist the types of changes, such as extending the school year, that may be required to help students catch up.

Your research center recently announced an initiative focused on states and districts learning from one another. How will this project work?

One potential strength of the U.S. system is that states and districts are choosing different solutions to shared problems such as absenteeism and declining literacy: “science of reading” initiatives vary dramatically from state to state; many, but not all, districts have implemented cellphone bans. I say it’s a “potential strength” because in order to benefit from it, we need to learn which interventions are working and which are not. States cannot learn from looking solely at what’s happening within their own borders; they need to see what’s working in other states.

Unfortunately, there’s no one organizing a cross-state effort focused on efficacy. Even if the policy debate in D.C. were less polarized, it would be awkward for the federal government to evaluate the efficacy of state reforms. I think that’s a role that a national university such as Harvard can play. We’ve launching a cross-state effort, called the “States Leading States” project. We’re going to work with a group of four or five states over the next few years to learn about the efficacy of various policies — including those focused on improving literacy, reducing chronic absenteeism, and boosting middle school math. We will work with states to learn what’s working and then spread what we learned to other states, through inter-state organizations such as the National Council of State Legislators, the National Governors Association, and the Council of Chief State School Officers. I can’t think of anything more important right now than supporting those state leaders who are willing to follow the evidence.