A study co-authored by economist David Deming examines how technology has changed the U.S. labor market over 100 years.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Is AI already shaking up labor market?

4 trends point to major change, say researchers who studied century of tech disruptions

A new paper by Harvard economists David Deming and Lawrence H. Summers offers early evidence of artificial intelligence shaking up the workforce.

The study measures more than 100 years of “occupational churn” — or each profession’s share in the U.S. labor market — for a historical look at technological disruption. It revealed a stretch of stability between 1990 and 2017 that runs counter to popular narratives about robots stealing American jobs. But the research also uncovered a recent shift, with the authors identifying several trends driven, at least partly, by AI.

“We really thought the paper would say something like, ‘See, I told you so. Things aren’t changing all that much,’” said Deming, the Isabelle and Scott Black Professor of Political Economy at Harvard Kennedy School and Faculty Dean of Kirkland House. “But when we got into the data, we found the story was a bit more subtle — and more interesting in some ways — than anything we expected.”

For years, Deming and Summers had talked about gauging occupational churn in the U.S. labor market over time. “It would be a systematic way to measure how much all these different types of technology have affected work,” explained Deming, the paper’s lead author.

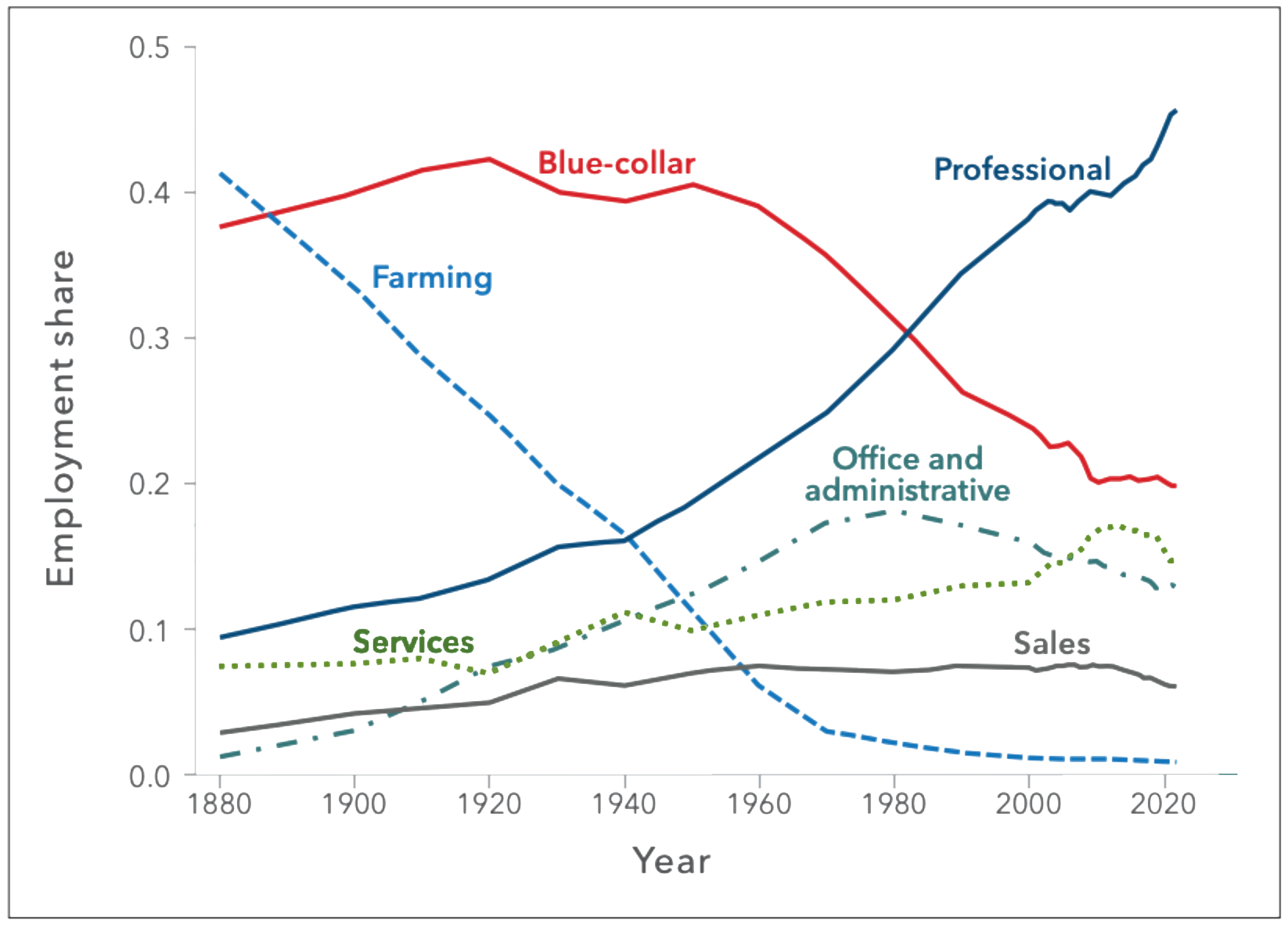

Labor market volatility over last century

Employment share by industry, 1880-2024.

Source: “Technical Disruption in the Labor Market”

Last year the economists applied the metric with help from Kennedy School predoctoral fellow Christopher Ong ’23, the paper’s third author. Their findings, drawn from 124 years of U.S. Census data, originally appeared in a volume published last fall by the Aspen Economic Strategy Group. Summers, a member of the OpenAI board of directors, shared further predictions in a live interview at the Aspen Ideas Festival.

Summers was initially surprised by the level of volatility uncovered in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s due to the rise of what are called “breakthrough general-purpose technologies.” “But when I thought about it, it wasn’t surprising,” said the Charles W. Eliot University Professor and Frank and Denie Weil Director of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard Kennedy School. “It used to be that only a very limited number of people used keyboards. Now everybody uses keyboards and there are fewer people whose whole job is to use keyboards. That turned out to be a very big structural change that the economy managed.”

The 2000s and 2010s were characterized by what Deming called “automation anxiety.” As evidence, he pointed to an influential study from 2013 asserting that 47 percent of U.S. occupations were at imminent risk of displacement by computers. But the occupational churn metric showed the pace of disruption slowing by 1990 as the labor market entered a stretch of low churn.

Then another surprise appeared in the data. “From 2019 onward,” Deming said, “it looks like things were changing quite a lot.”

“Everybody should be thinking about AI, no matter what they do for a living.”

Lawrence H. Summers, study co-author

Is AI a breakthrough technology along the lines of keyboards, electricity, and computer-based manufacturing? The co-authors’ findings led them to believe so. As evidence, they outline four emerging trends in the U.S. job market.

The first concerns the end of what economists have termed job polarization — a barbell-shaped pattern, with the labor market growing at the top and bottom of the wage distribution.

What appeared more recently, the researchers found, is a one-sided pattern favoring well-compensated employees with high levels of training and skill. “The trend people were worried about in the 2000s was the downward ramp,” Deming said. “That meant low-paid jobs were growing but middle- and high-paid jobs were not. It’s only in the late 2010s that we see an upward ramp, with mostly high-paid jobs that are growing.”

Another trend, related to the first, finds a recent skyrocketing of science, technology, engineering, and math jobs following a surprising dip in the 2010s. The share of jobs in STEM — including software developers and data analysts — grew from 6.5 percent in 2010 to nearly 10 percent in 2024. “That doesn’t sound like a lot,” Deming said. “But it’s an almost 50 percent increase.”

Analyzing data sourced from the Census as well as the Federal Reserve Bank showed firms are not only hiring more technical talent, they’ve started to make record-breaking investments in frontier technologies such as AI. “You really don’t need to speculate about AI’s impact on the labor market,” Deming noted of these findings. “Investment in AI is already changing the distribution of jobs in the economy.”

The research also uncovered flat or declining employment specifically in low-paid service work. Charting the occupational churn in this sector, which saw enormous growth from 1980 to the early 2000s, revealed a cliff as of 2019. AI is just one possible explanation, Deming emphasized. Other contenders include higher wages, a tighter job market, and temporary disruptions related to COVID-19.

“But it doesn’t look like many of these jobs are coming back,” Deming added. “The ones that have returned are in food service, personal services like manicurists and hairdressers, medical assistants, and some cleaning jobs.”

The paper’s fourth trend suggests an especially deep plummet, driven by technology, in retail sales jobs. Between 2013 and 2023, the share of retail sales jobs dropped from 7.5 to 5.7 percent of the job market, a reduction of 25 percent.

The co-authors note that the e-commerce sector was an early adopter of predictive AI, and has more than doubled its share of all retail sales since 2015.

“I see the pandemic as an accelerant, as something that was going to happen anyway,” Deming said. “When people were told it’s dangerous, possibly even deadly, to go shopping — now they had to shop online — they discovered it actually wasn’t so bad and formed new habits.”

“Everybody should be thinking about AI, no matter what they do for a living,” Summers added. “Because AI can be highly empowering. But it also means certain types of activities won’t be done by people anymore.”

The paper contains a nugget of insight for knowledge workers in sectors like finance, management, and journalism. Automation has indeed claimed American jobs over the last century. In a Substack post, Deming cited the early 20th-century example of telephone operators. But AI’s impact is more likely to enable short-term boosts to productivity with longer-term threats of displacement by workers more adept with the technology.

“When companies start to get squeezed — when we hit the next recession or something — they’re going to start expecting more out of knowledge workers,” Deming said. “They won’t want that memo in two days, because they know this technology is available. They’ll want it in two hours.”