The brain’s gatekeepers

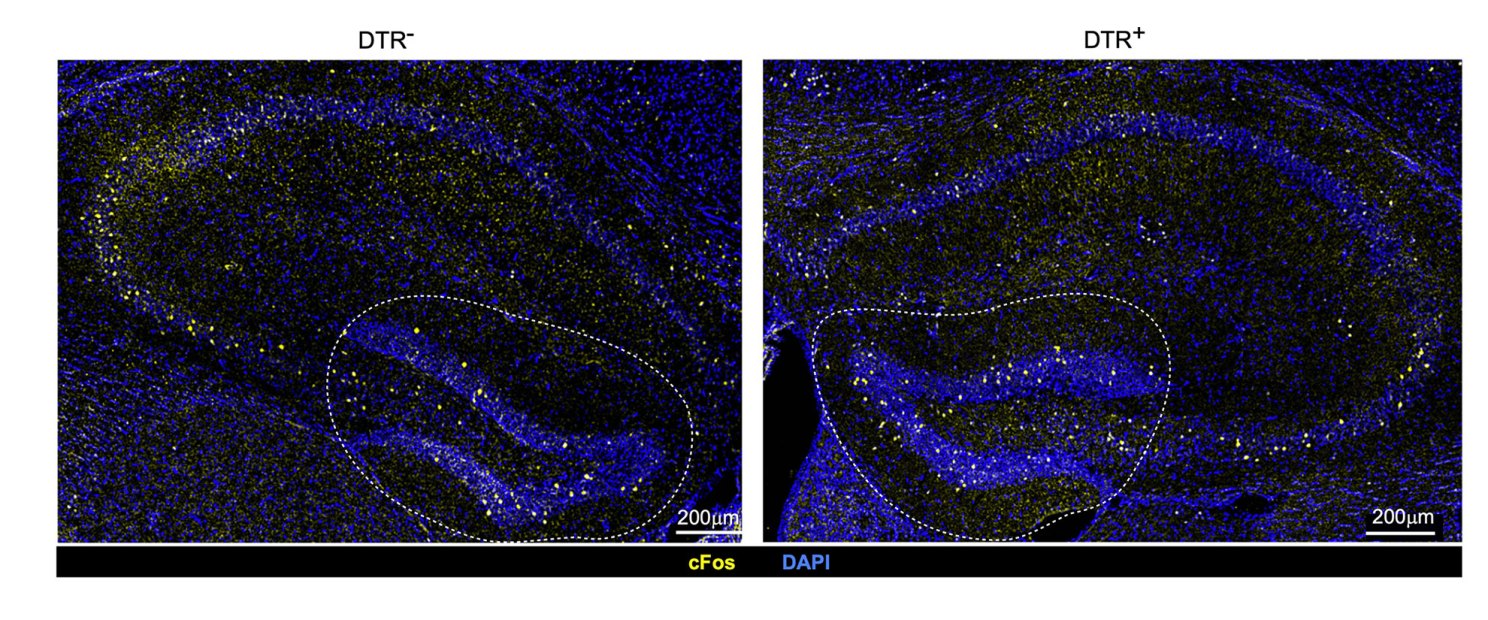

Differences in neuronal activation in mice with intact immune cells called regulatory T cells or Tregs (left) and depleted Tregs (right). The finding demonstrates that Tregs play a role in ensuring healthy neuronal activity under normal conditions.

Credit: Mathis/Benoist Lab

HMS research IDs special class of cells that safeguard immunity and memory, and may one day treat neurodegenerative disease

Immune cells called regulatory T cells have long been known for their role in countering inflammation. In the setting of infection, these so-called Tregs keep the immune system from going into overdrive and mistakenly attacking the body’s own organs.

Now scientists at Harvard Medical School have discovered a distinct population of Tregs dwelling in the protective layers of the brains of healthy mice, and their repertoire is much broader than inflammation control.

The research, published Tuesday in Science Immunology, shows that these specialized Tregs not only control access to the inner regions of the brain but also ensure the proper renewal of nerve cells in an area of the brain where short-term memories are formed and stored.

The research, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, represents an important step toward untangling the complex interplay of immune cells in the brain. If replicated in further animal studies and confirmed in humans, the research could open up new avenues for averting or mitigating disease-fueling inflammation in the brain.

“We found a thus-far-uncharacterized, unique compartment of regulatory T cells residing in the meninges surrounding the brain and involved in an array of protective functions, acting as gatekeepers for other immune cells and involved in nerve cell regeneration,” said study senior author Diane Mathis, the Morton Grove-Rasmussen Professor of Immunohematology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS.

The work adds to a growing body of research showing that Tregs go above and beyond their traditional immune-regulatory duties and act as tissue-specific guardians of health, the researchers said. Earlier work led by Mathis showed that Tregs in the muscles get activated during intense physical activity to fend off exercise-induced inflammation and maintain muscle health.

“The Tregs that we found in the meninges are endowed with skills customized to fit the needs of this particular tissue,” said study lead author Miguel Marin-Rodero, a doctoral student in the immunology program at Harvard Medical School in the Benoist-Mathis lab. “These findings are consistent with other studies showing that Tregs turn on and off specific genes to match the identity and needs of the organ they reside in — they are really the best immune cells ever.”

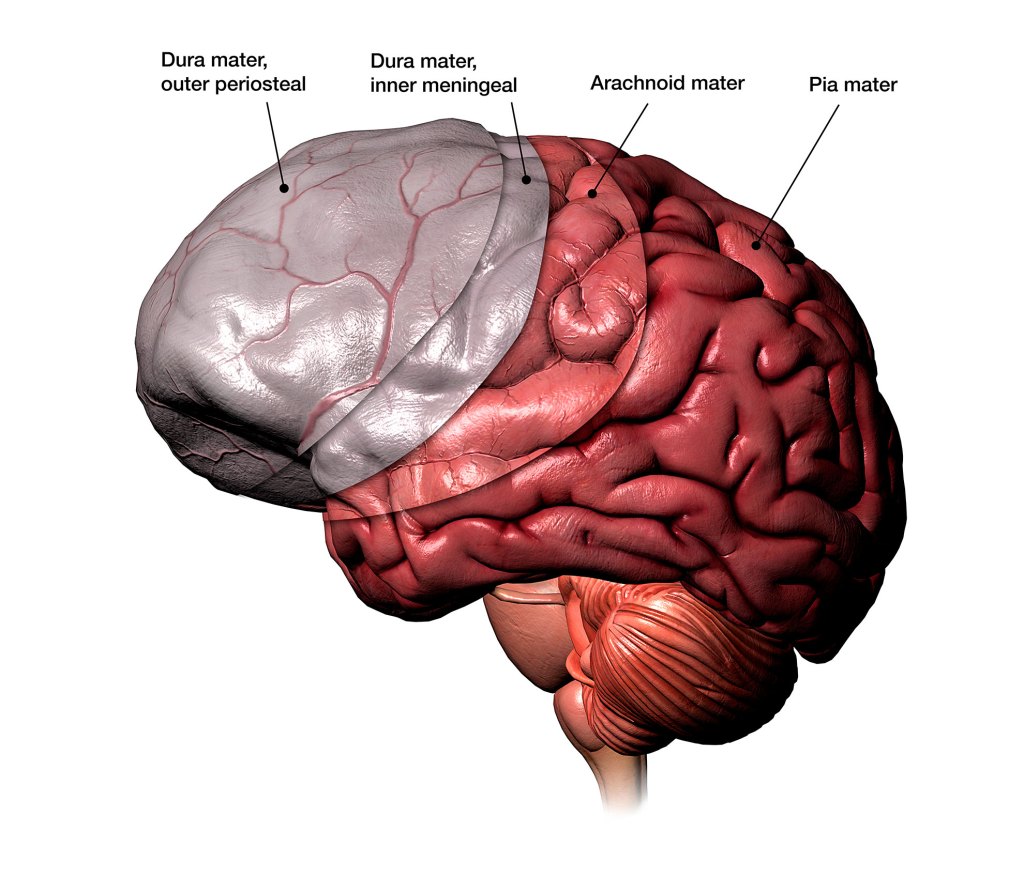

Illustration of the three protective layers under the skull.

Hank Grebe, 2018/Getty Images

Tregs dwelling at the brain border act as gatekeepers

The meninges, three protective tissue layers under the skull, shield the brain and spinal cord from injury, toxins, and infection. This brain border hosts a diverse population of immune cells. Most of these cells are innate, and their roles and functions have been fairly well defined. But the brain border is also home to adaptive immune cells, many of which develop after birth, whose roles in brain immunity have remained somewhat elusive. The new study provides a detailed profile of Tregs — a type of adaptive immune cell — at the body-brain interface.

To understand the role of Tregs in this context, the researchers used a genetic technique to deplete them from the meninges of mice. The meninges of animals lacking Tregs produced higher than normal levels of an inflammatory chemical called interferon-gamma, causing widespread inflammation of the meninges. The removal of Tregs also opened the brain’s inner regions to interferon-producing, inflammation-fueling immune cells and activated immune cells that reside nearby but are normally kept at bay by Tregs. No longer restrained by Tregs, these immune cells infiltrated the brain and caused widespread inflammation and tissue damage. The resulting inflammation, the researchers said, was reminiscent of the damage and immune-cell activity seen in human and mouse brains with Alzheimer’s disease.

“These experiments demonstrate that Tregs in the meninges act as gatekeepers to guard the innermost regions of the brain,” Marin-Rodero said.

Absence of Tregs scars a memory-making region of the brain

Next, researchers examined the effect of depleting Tregs on various brain regions. Not all brain regions were affected equally. In the absence of Tregs, inflammatory cells clustered mostly in the hippocampus, an area of the brain involved in learning, memory formation and storage, and spatial navigation. The hippocampus is also one of few regions in rodent and human brains that continues to produce neurons into adulthood, so an assault on this area could have repercussions for memory formation.

Neural stem cells in the hippocampus underwent the most dramatic changes as a result of Treg depletion. These cells are critical because they are capable of becoming many other specialized brain cells. But in the absence of Tregs, their ability to differentiate into other cells was critically hampered. Their activity slowed down or altogether ceased, and they started to die off.

Treg depletion appeared to leave a “scar” in the hippocampus, leading to a persistent functional defect in short-term memory formation, the researchers said. Treg-deficient animals developed problems with short-term memory that persisted even months after their Tregs were restored to normal.

But how exactly do Tregs keep other cells in check?

In a final set of experiments, the researchers found that in the brains of healthy mice, Tregs keep inflammation-driving immune cells under control by competing for a shared resource — a growth factor called IL-2. When Tregs were removed, other immune cells were able to gobble up this cellular fuel, multiply quickly, and produce inflammatory proteins.

A pathway to understand and treat neurodegenerative diseases

Inflammation has been long implicated in multiple neurodegenerative diseases, so the question that comes next, Mathis said, is: Do Tregs in human brains play a role in curbing the inflammation that drives these degenerative processes?

Mathis’ team is currently studying this very question using a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Simultaneously, they are also working with colleagues in the neuropathology and neurosurgery departments at Massachusetts General Hospital to investigate this process in human brains with Alzheimer’s.

In recent years, Treg-based therapies have generated excitement about the possibility of using these cells in an organ-specific or tissue-specific manner to treat immune-mediated diseases. These efforts include lab-modified Tregs (CAR-Tregs and T-cell receptor Tregs) as well as the design of therapeutic molecules that could alter Treg function in a precise and site-specific manner.

“Understanding exactly how Tregs perform their protective duties could one day help us design treatments that boost their activity to modulate a wide range of disease processes,” Mathis said.

Additional authors included Elisa Cintado, Alec J. Walker, Teshika Jayewickreme, Felipe A. Pinho-Ribeiro, Quentin Richardson, Ruaidhrí Jackson, Isaac M. Chiu, Christophe Benoist, Beth Stevens, and José Luís Trejo.

The research described in this story was supported by the JPB Foundation, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, National Institutes of Health, NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Additional support was provided through HHMI and the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund and by a predoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness).