Images courtesy of Baker Library Special Collections; Ansel Adams test photos. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Polaroid gave her a shot. She helped revolutionize photography.

Meroë Morse — focus of Baker Library exhibition — led company’s researchers during innovative era

Meroë Morse had no formal background in business or science when she started at Polaroid in 1945, but within a few years she rose to become manager of black-and-white photographic research and later to director of special photographic research, a notable achievement for a woman in the 1950s and ’60s.

A new exhibition at the Business School’s Baker Library is putting the focus on Morse and her contributions to the development of instant photography — launched commercially by Polaroid in 1948. The collection, “From Concept to Product: Meroë Morse and Polaroid’s Culture of Art and Innovation, 1945–1969,” on view in Baker’s north lobby through April 18, draws on the library’s extensive holdings of the Polaroid Corporation Collection.

“The function of industry is not just the making of goods, the function of industry is the development of people.”

-Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid

A culture of innovation

Edwin H. Land, Polaroid’s founder, cultivated a creative culture within his research and manufacturing enterprise, building an interdisciplinary community devoted to technical and artistic excellence.

Morse, an art history graduate of Smith College, found exceptional opportunities for women in the post-war era at Polaroid. She oversaw round-the-clock shifts of researchers conducting thousands of experiments in the company’s Cambridge laboratory, and met increasing demands for new Polaroid films as the popularity of instant photography soared.

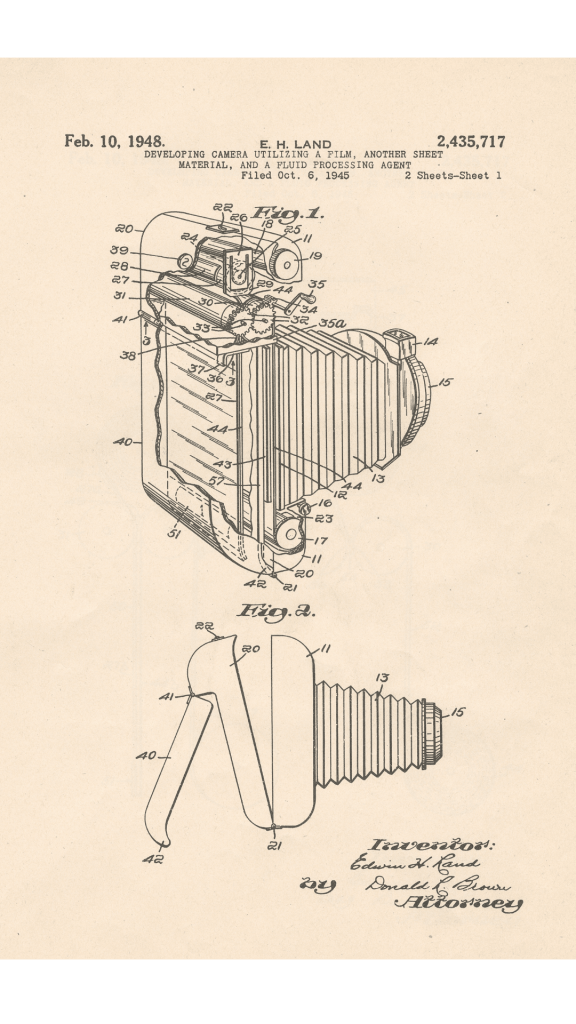

Instant photography is launched

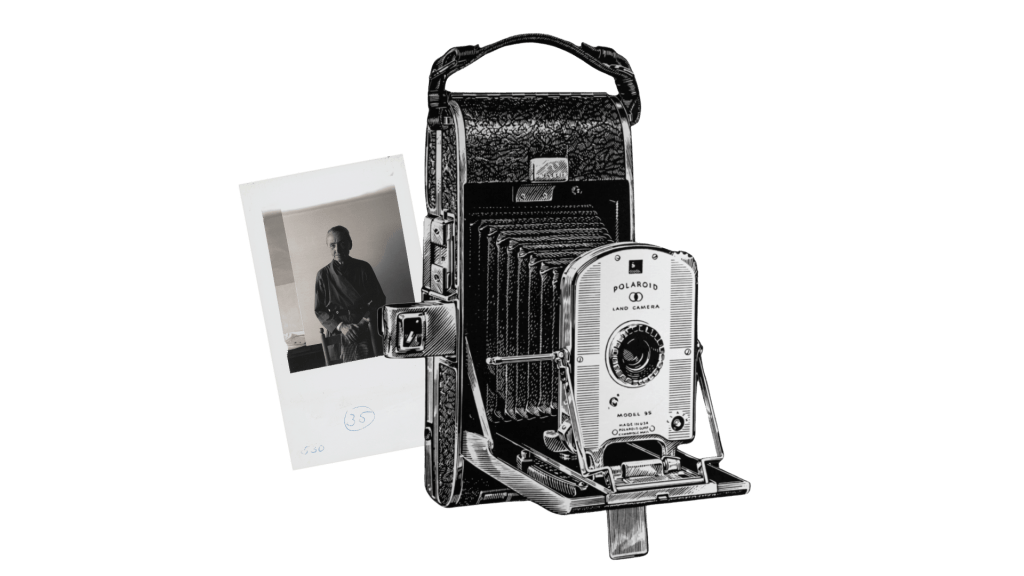

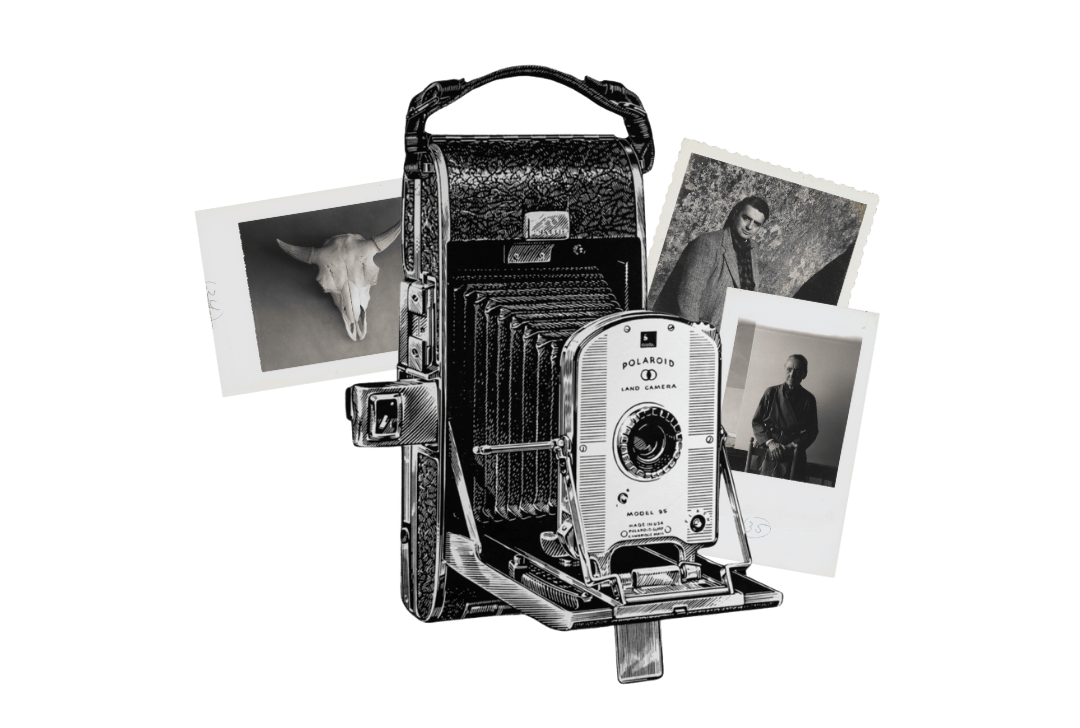

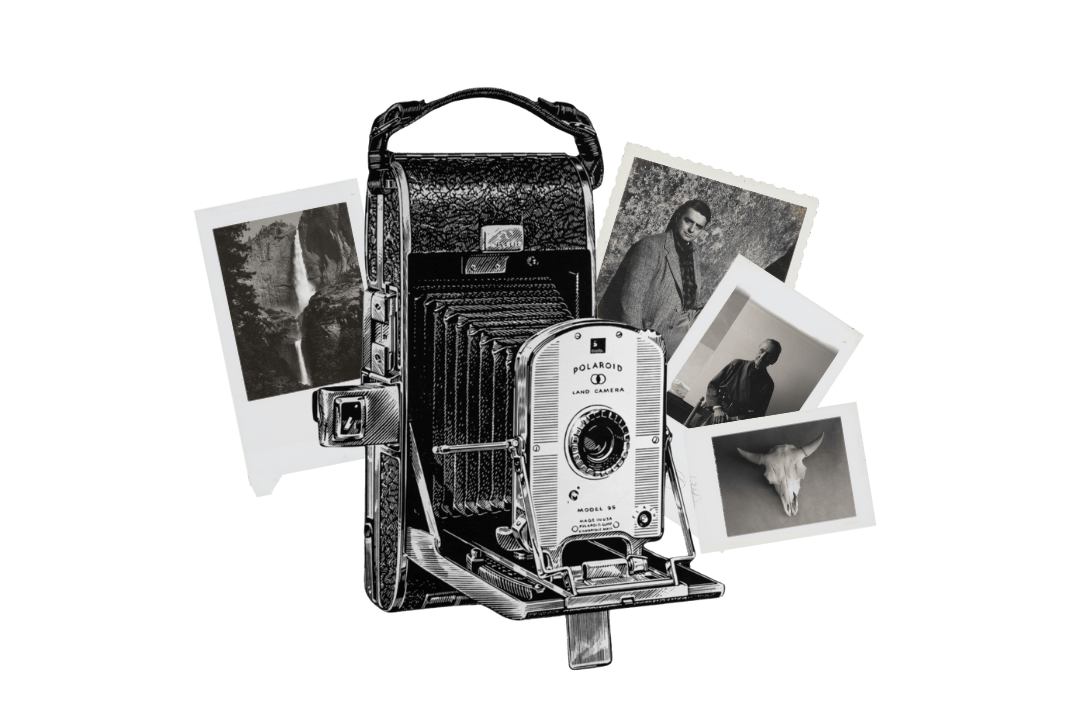

The first instant film and camera sold for $1.75 and $89.75 respectively on Nov. 26, 1948, in Boston’s Jordan Marsh department store. The camera measured 10½ by 4½ by 2½ inches and weighed four pounds, two ounces. It featured an optical foldout viewfinder, a three-element 135-mm f/11 lens, and shutter speeds from 1/8 to 1/60 of a second. All 56 cameras sold out that day.

Morse holds a hand-made wheel containing names of some of the developing chemicals used in instant photography.

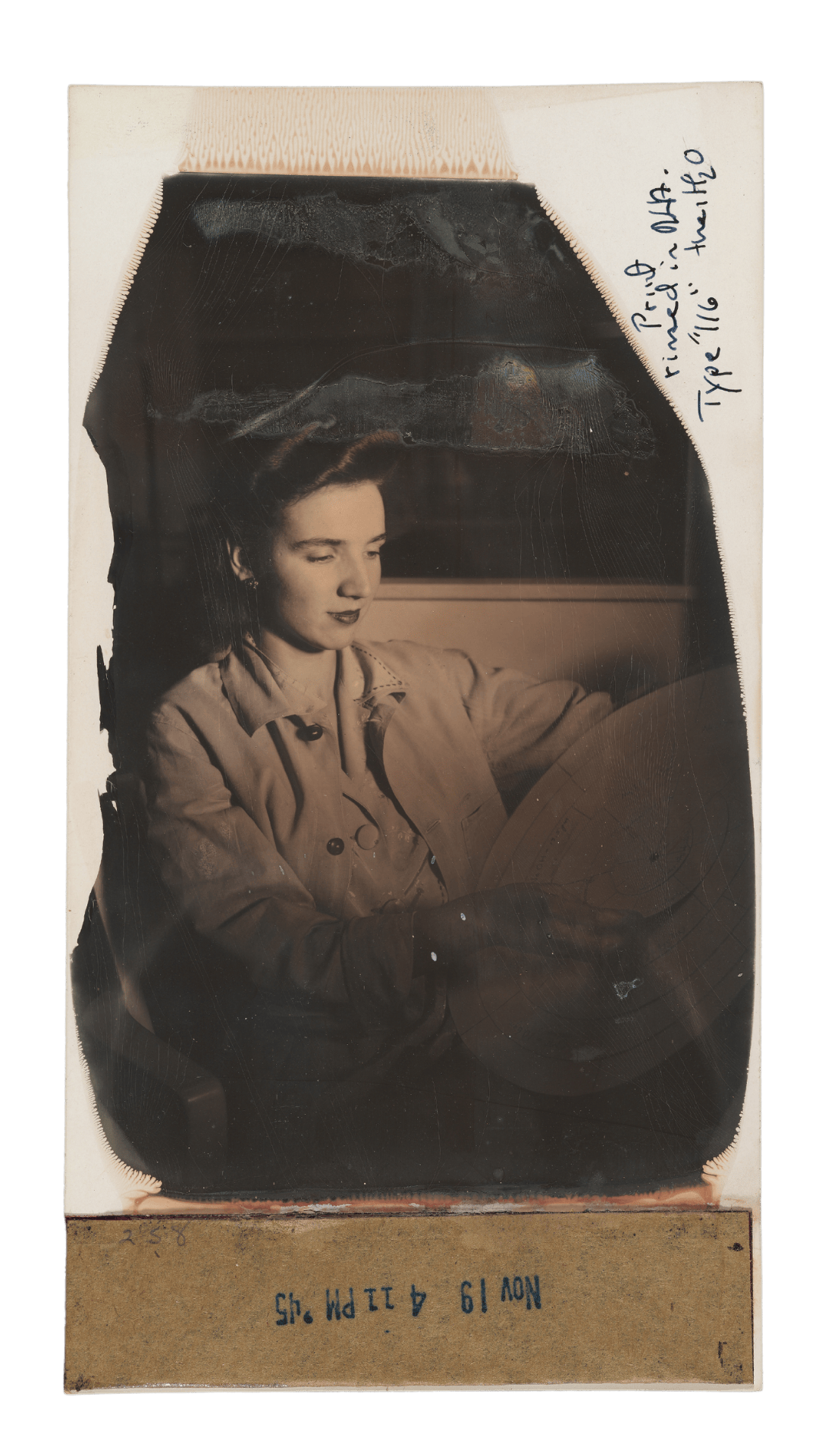

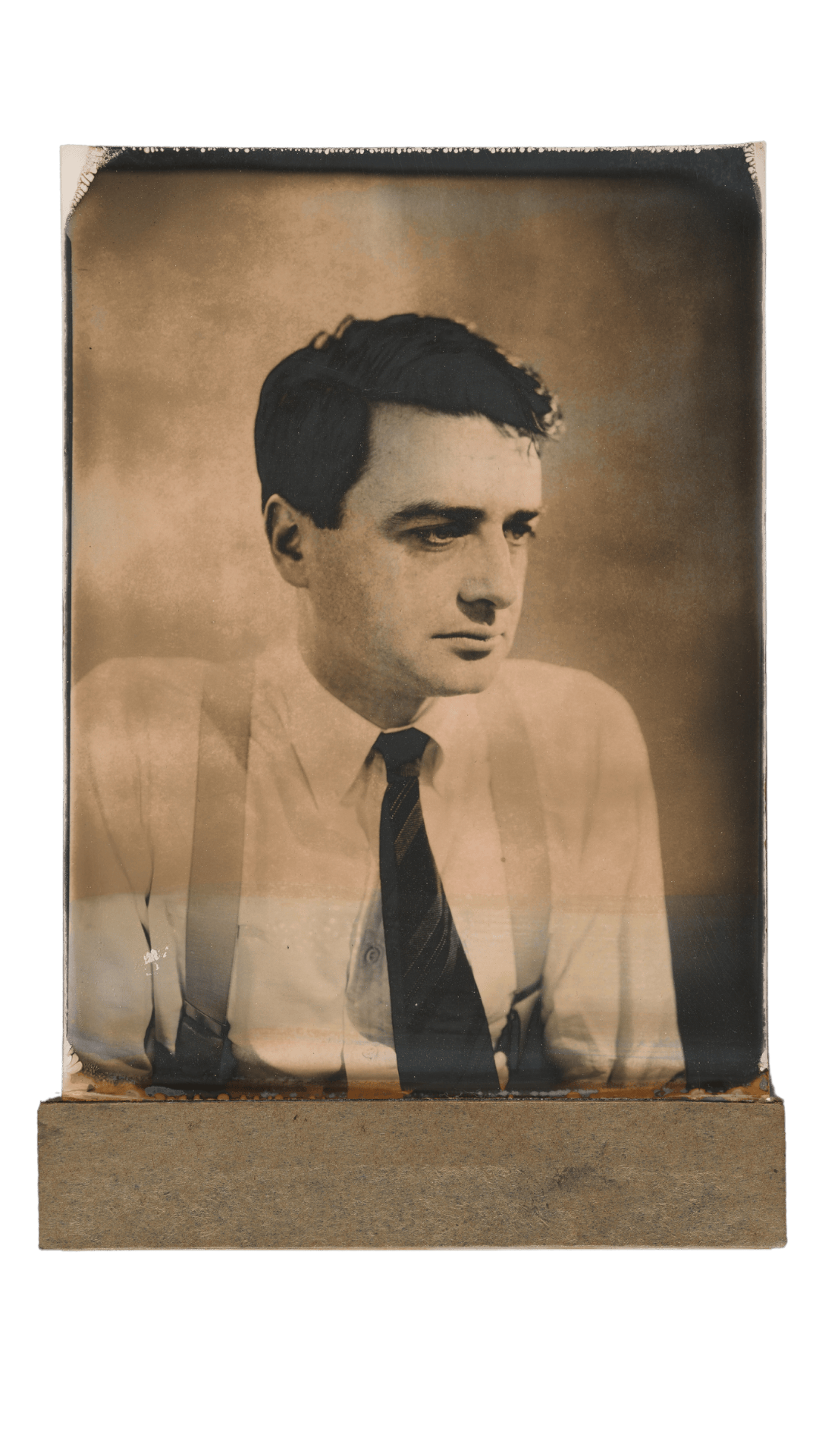

Early Polaroid test photograph of Edwin Land in November 1945.

The first Polaroid film, Type 40, produced sepia-toned prints with a limited tonal range.

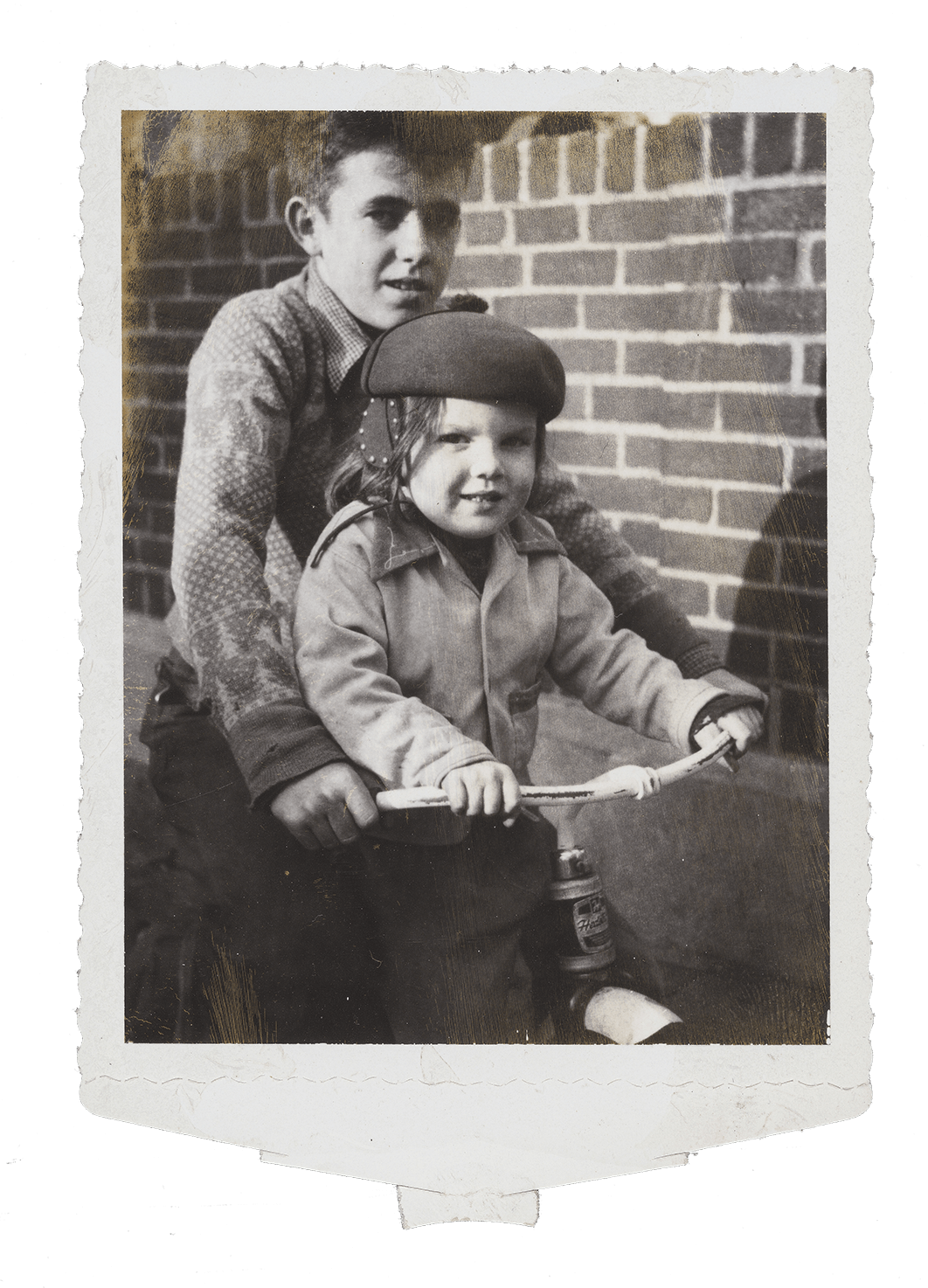

Children pose for a test photo.

In 1950, the company introduced black-and-white film Type 41.

Research in black and white

In 1948, Morse became the laboratory supervisor responsible for photographic materials. The earliest Polaroid film, Type 40, produced sepia-toned prints that had limited tonal range. Morse and her lab looked to produce black-and-white images that exhibited greater detail and a color palette more familiar and appealing to consumers. In 1950, after two years of intensive work, the company introduced black-and-white film Type 41. The film produced prints that exhibited finer detail and, as U.S. Camera enthused, created “pictures-in-a-minute of exceptional tonal values.” The Detroit Free Press reported that Land credited Morse with “valuable assistance in research that led to the new film.”

Ansel Adams and Polaroid

Morse also served as chief liaison to Ansel Adams, the renowned landscape photographer. A principal consultant for Polaroid from 1948 until his death in 1984, Adams tested the company’s prototype cameras and film. He reviewed technical and design aspects of Polaroid prototypes, from the wording of instruction manuals to the tonal values of finished prints.

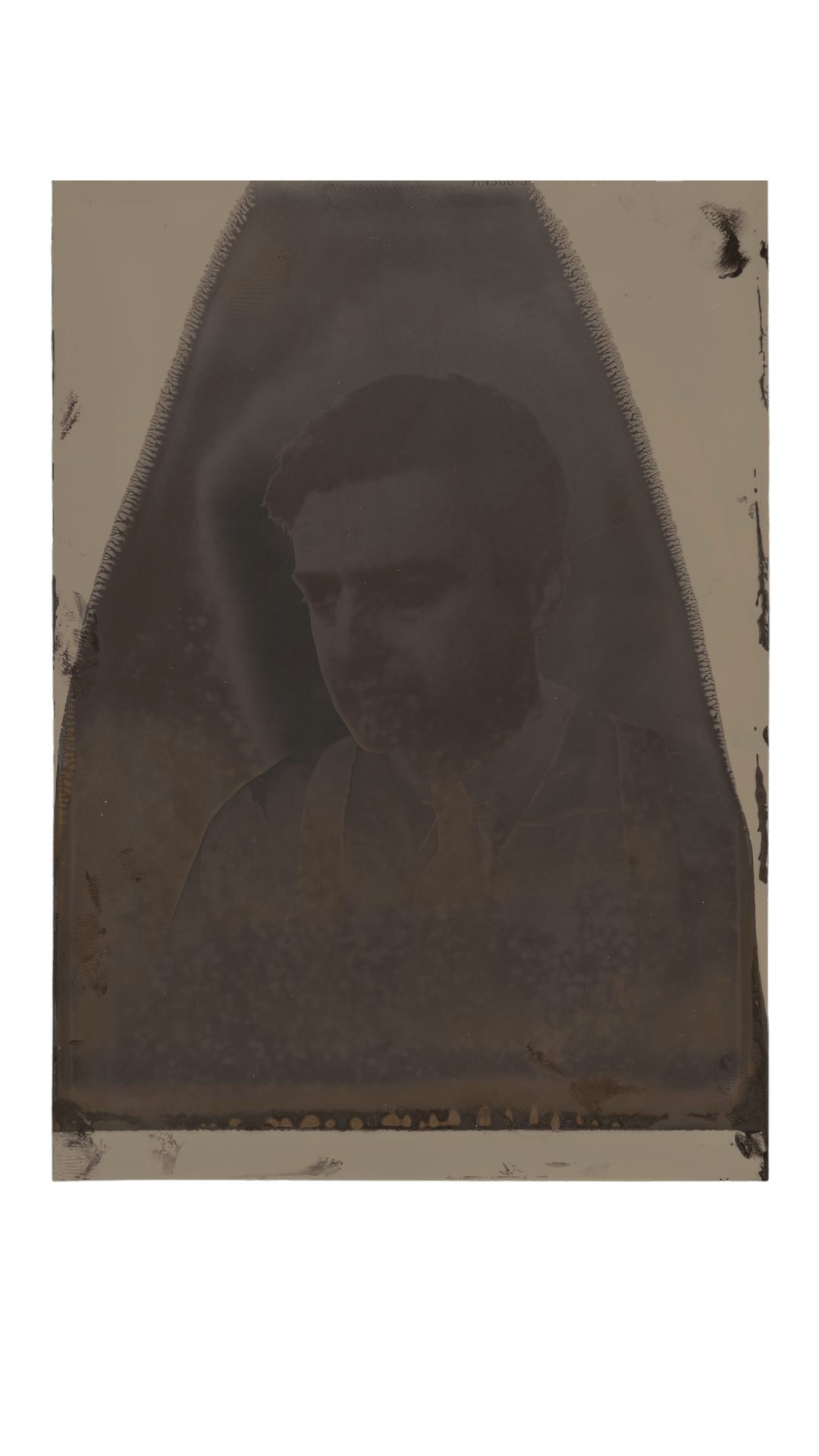

Ansel Adams Polaroid test photos.

Ansel Adams test photos. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

Portrait of Edwin Land.

Ansel Adams test photos. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

Polaroid test photo from the Southwest.

Ansel Adams test photos. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

Polaroid test photo from California.

Ansel Adams test photos. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

The exhibition was organized by Baker Library Special Collections and Archives, with support from the de Gaspé Beaubien Family Endowment. This text is drawn from the exhibition catalog. Find more information at the Baker Library website.