President-elect Donald Trump waves at an election night watch party at the Palm Beach Convention Center.

Evan Vucci/AP Photo

Did Trump election signal start of new political era?

Analysts weigh issues, strategies, media decisions at work in contest, suggest class may become dominant factor

President-elect Donald Trump’s election victory over Vice President Kamala Harris was made possible partly by a significantly expanded coalition of multi-ethnic, working-class voters, signaling a potentially seismic shift in the American political landscape, according to a political analyst.

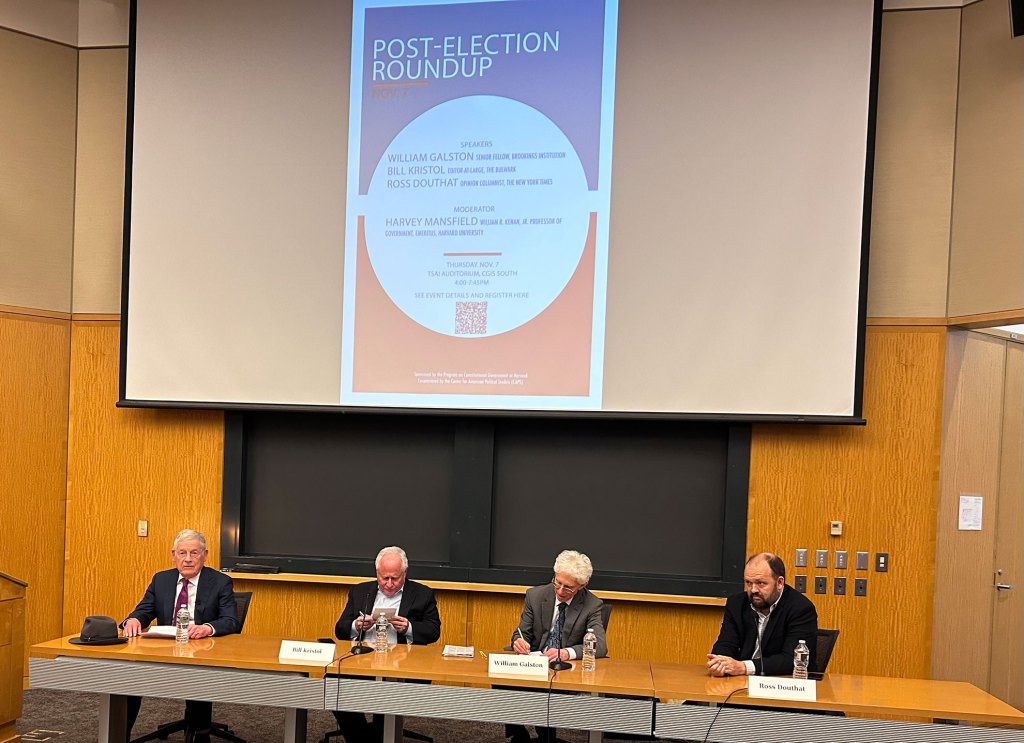

“I believe that we are in a new political era in which class will be the dominant factor in political divisions,” said William Galston, a columnist for The Wall Street Journal and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, during a panel discussion Thursday hosted by the Center for American Political Studies.

Analysts at the election post-mortem, moderated by Harvey Mansfield, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Government, Emeritus, noted Trump made gains with voters in every age group, across racial and ethnic demographics, particularly Hispanic and Black men, and even improved over 2020 with women.

Class and gender were more determinative than race and ethnicity this year, Galston noted, with class, as defined by educational level rather than income, being the most important. The split between people with higher and lower levels of education is a development the country “will be wrestling with for the next generation with consequences that I can’t begin to predict,” he said.

The group noted the Trump campaign correctly predicted wide-ranging voter discontent over the economy and immigration would override any misgivings about their candidate’s personality or behavior. And Trump’s recent pledge to veto a national abortion ban appeared to allay concerns with many voters over an issue Democrats had expected would drive turnout their way.

They also noted the campaign’s media strategy proved very effective. TV ads attacking Harris as being too liberal did some damage. And the unconventional decision to put less emphasis on mainstream news outlets in favor of more friendly, less overtly political settings, like “The Joe Rogan Podcast,” along with aggressive use of social media influencers, crypto and gambling events, and internet memes, helped the campaign reach likely supporters, the panelists said.

The Harris campaign had much to overcome, tied as it was to the coattails of a deeply unpopular administration that was blamed for the nation’s high inflation and problems with border security and immigration, the analysts said.

President Biden ran on restoring normalcy to the pandemic-battered U.S. economy and using his considerable foreign policy chops to cool global hotspots and repair international relations damaged by Trump, said Ross Douthat ’02, opinion columnist at The New York Times, who anticipated that Trump would prevail.

Instead, he said, voters faced much higher prices on essentials like gas and food and witnessed a botched U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and two wars erupt in Ukraine and in the Middle East.

Trump “said a lot of wild and deplorable things over the course of the 2024 election but having lived through the first Trump administration in which there was a huge disconnect between Trumpian rhetoric and the actual realities of governance, I don’t think it was that surprising that the voting public [told themselves] if we went through this for four years and things were OK, and Donald Trump did not become a fascist dictator, we can go through it for four more years’” because he offers better prospects than the alternative, Douthat said.

In addition, Biden’s seeming retreat from his 2020 pledge to be a one-term “transitional president,” waiting until July to step aside, gave Harris no time to introduce herself to voters and to lay out and sharpen the substance and presentation of her agenda in just three months put her at a great disadvantage from the outset, said Galston.

Without a primary, Harris also had no real chance to establish an identity independent of Biden, making it easier to tie her to everything voters disliked about his administration. And arguments that Harris and Democrats thought would be key, such as reproductive rights and Trump’s role in the Jan. 6 attack, proved less powerful than hoped.

“There is a mountain of political science evidence to the effect that for people who feel hard-pressed economically or insecure physically, democracy is a luxury good,” said Galston.

Then there was the appeal of Trump himself. The president-elect has had 50 years as a celebrity, skillful marketer, and TV performer, so it’s not surprising that he excels at creating effective political images and viral content, like pretending to serve McDonald’s french fries, that cut through today’s fragmented media landscape and deliver his intended messages, said Bill Kristol ’73, Ph.D. ’79, a longtime conservative intellectual and founder of the now-defunct Weekly Standard, who became a critic of the Republican Party under Trump.

He said Trump returns to office with a more supportive Republican majority in the Senate and possibly the House, expanded presidential protections conferred by the Supreme Court, and a plan to purge the federal government of those who would try to block his initiatives. And so, he appears much more powerful than he was in 2016.

Referencing Karl Marx’s famous quip about history repeating itself the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce, Kristol said about a second Trump term: “What makes me most worried about the next four years is that it could end up being ‘first time farce, second time tragedy.’”