Manifesting Black history in 3D

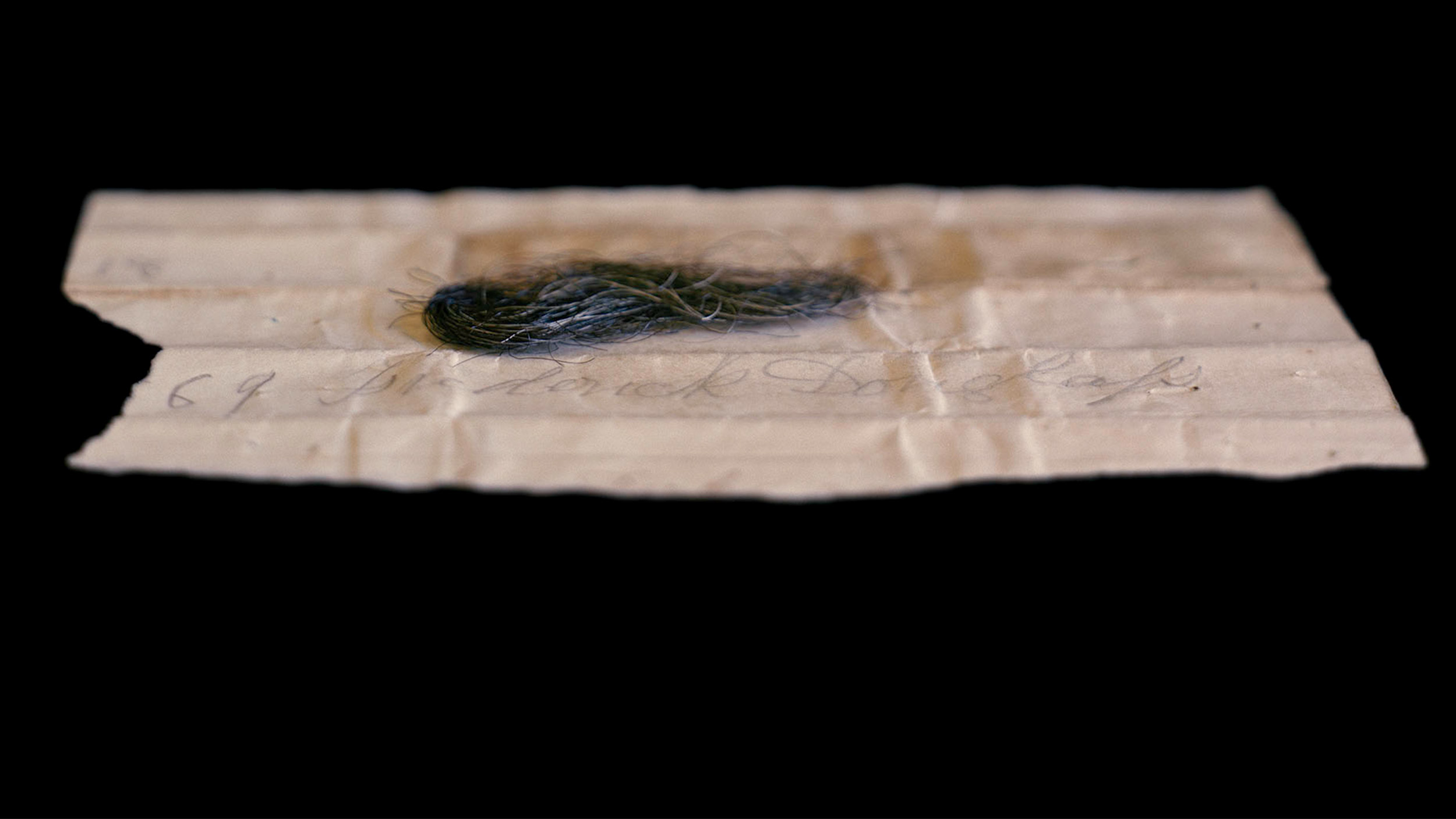

Frederick Douglass’ hair.

Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester © Wendel A. White

From Frederick Douglass’ hair to Malcolm X’s tape recorder, Wendel White’s new book puts an abundance of artifacts on display

When Wendel A. White first encountered a lock of Frederick Douglass’ hair in an archive, the direction of his work took a radical shift. White had been concentrating on photographing landscapes as a way to explore Black history, but this discovery turned his attention to what he describes as “a remarkable reliquary of artifacts.” Venturing into archives, libraries, museums, and historical societies, he has sought to “excavate Black history through material culture.”

White photographed African American materials housed in private and public collections throughout the 13 original U.S. colonies and Washington, D.C., for his project “Manifest: Thirteen Colonies.” His subjects are both rare, singular objects — such as a twisted fragment of stained glass from the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing — and everyday material such as diaries, documents, photographs, and souvenirs.

Some images are related to famous historical figures such as Malcolm X (a tape recorder he used), James Baldwin (his inkwell), Phillis Wheatley (her book of poems), and Zora Neale Hurston (manuscripts including “Their Eyes Were Watching God”).

Tape recorder used by Malcolm X at Mosque #7.

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C. © Wendel A. White

James Baldwin’s inkwell.

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; Gift of the Baldwin Family, Washington, D.C. © Wendel A. White

Tabletop voting machine, 1955.

Delaware Historical Society, Wilmington, Del. © Wendel A. White

Halftone printing plate.

Roscoe Conkling Simmons, Artifacts. Nathan Marsh Pusey Library, Harvard University Archives © Wendel A. White

Civil War-era brogan-style shoe (1863-1865).

North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh, N.C. © Wendel A. White

Genealogical chart with hair, Caroline Bond Day, 1932.

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University © Wendel A. White

Some are connected to unknown figures, such as the owner/maker of a shoe, perhaps an African American Civil War soldier. Others speak to slavery and empowerment. “These artifacts are the forensic evidence of Black life and events in the United States,” White explains.

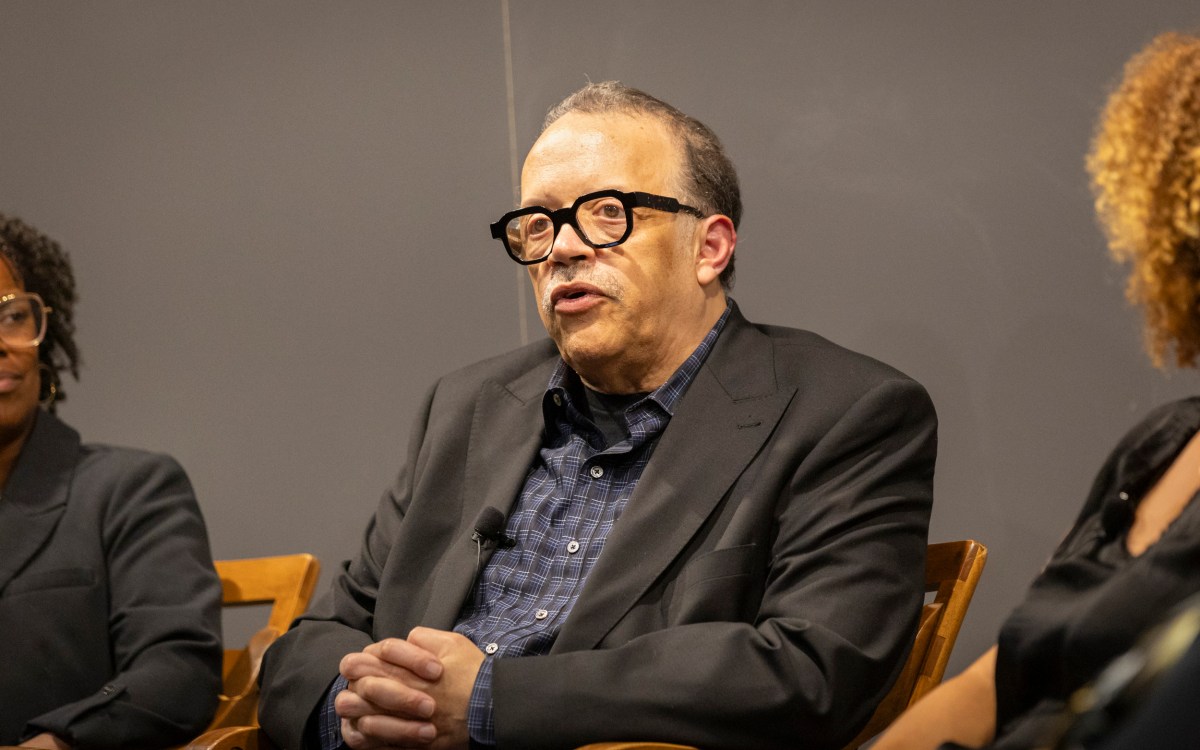

As the 2021 Robert Gardner Fellow in Photography, White’s work is on view at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology through April 13, 2025, in the exhibition “Manifest: Thirteen Colonies.” The exhibition is accompanied by a monograph, “Wendel A. White: Manifest | Thirteen Colonies,” (Radius Books/Peabody Museum Press, Summer 2024), which includes text by Deborah Willis, Cheryl Finley, Leigh Raiford, Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Chief Campus Curator Brenda Dione Tindal, and Peabody Museum Curator of Visual Anthropology Ilisa Barbash. Book contributors will be on hand for a book launch and conversation Sept. 26 and a related free ArtsThursdays event on the same evening.

White’s use of shallow focus refocuses the gaze we expect to have on objects, writes Barbash. “He artfully draws out those qualities he feels are particularly meaningful and emotionally impactful. And in compelling us to reckon with these insights, he reanimates these objects into vital components of our present.”

Two dolls that were part of the famous 1940s “Doll Test.”

Kenneth and Mamie Clark, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; Gift of Kate Clark Harris in memory of her parents Kenneth and Mamie Clark, in cooperation with the Northside Center for Child Development Washington, D.C. © Wendel A. White

One image that carries echoes from the past into our present is of two dolls, identical in every way except their skin color. Not just any dolls, these were part of the famous 1940s “Doll Test.” Psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark asked African American children ages 3–7 which doll they preferred. When a majority of the children selected the white doll, the Clarks concluded that “prejudice, discrimination, and segregation” gave the children a sense of inferiority and hurt their self-esteem. The Supreme Court cited the Clarks’ research in its groundbreaking desegregation decision, Brown v. Board of Education.

At Harvard, White selected a few items, including W.E.B. Du Bois’ Ph.D. thesis, “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1871.” He also chose a printing plate with a portrait of civic leader and journalist Roscoe Conkling Simmons, and one of White’s favorite things, a chart created by Radcliffe anthropologist Caroline Bond Day. Her book was published by the Peabody Museum in 1932 and offers a glimpse of the little-known Black scholar’s extraordinary research into the genealogies of Black American families in the 1930s.

Reflecting on the emotional reactions his images may provoke, White says, “Sometimes the things that I select are not things that everybody wants to look at or think about in both the white community and the Black community.” He references Isabel Wilkerson’s book “Caste”: “When you live in an old house, you may not want to go into the basement after a storm, to see what the rains have wrought. Choose not to look, however, at your own peril.”

Related story

-

Arts & Culture

Arts & CultureA photographer who makes historical subjects dance

Wendel White manifests the impetus behind his new monograph during Harvard talk