When Picasso’s haunting portrait of war came to Harvard

Exhibit captures early reaction to one of 20th century’s most famous works of art

Harvard students view “Guernica” at the former Fogg Art Museum in 1941.

Harvard Art Museums Archives

In the summer of 1937, Pablo Picasso finished a mural-sized painting portraying the bombing of the Basque town Guernica that would later become one of the most famous artworks of the 20th century and a powerful symbol of the brutality of war. When, just four years later, the painting arrived at Harvard as part of a world tour to raise funds for the Spanish Refugee Relief Commission, it caused both shock and awe.

Newspaper reviews from 1941 of the exhibit at the former Fogg Art Museum, now part of the Harvard Art Museums, called the 11-by-25-foot painting “spectacular and controversial” and “not pleasant to behold.” A Harvard professor who was then using “Guernica” in his fine arts course wrote that it “was painted to arouse indignation and protest and not to please.”

“Pierrot and Red Harlequin.”

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Arthur Pope

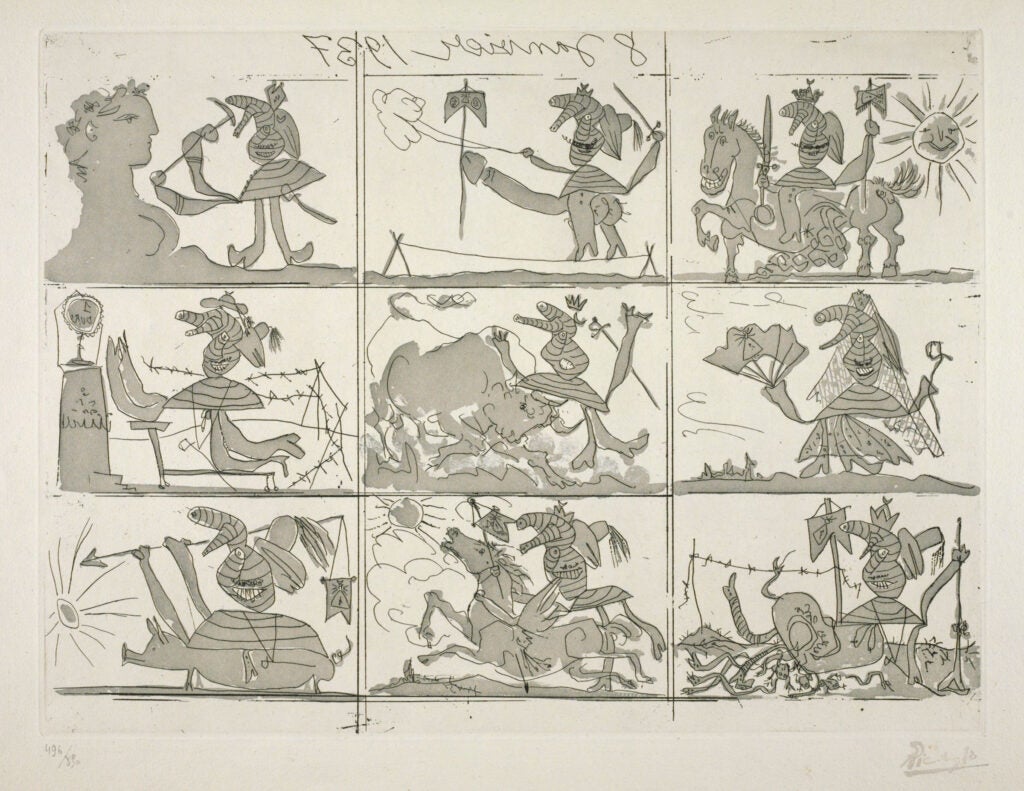

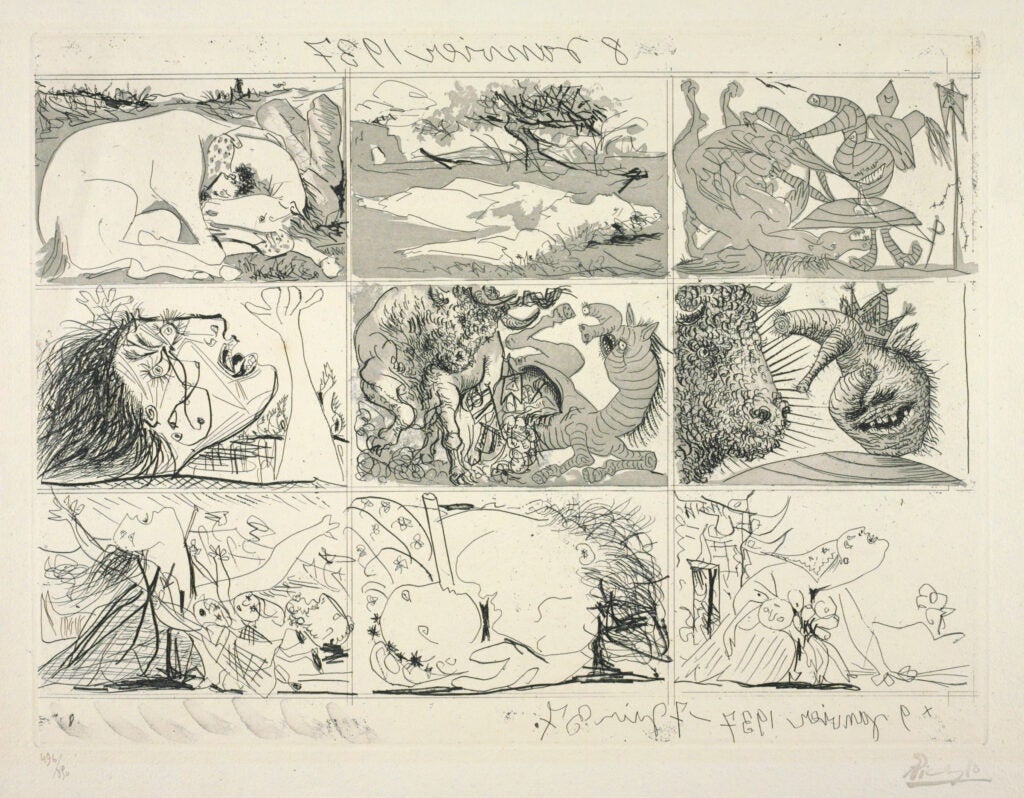

“Dream and Lie of Franco, I” and “Dream and Lie of Franco, II.”

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Francis H. Burr Memorial Fund

The story of how the painting came to Harvard twice in the 1940s is told through archival material in the installation “Picasso: War, Combat, and Revolution,” on view through May 5 at the Art Museums. The painting itself is not included in this exhibition — it remains permanently on display at the Reina Sofía in Spain — but other rare works by Picasso are shown that both echo and anticipate the themes of “Guernica”: death, war, combat, and love.

Suzanne Preston Blier curated the exhibit to complement her course “World Fairs.” In 1937, the Spanish Republican government had commissioned Picasso to create a work of art for its pavilion at the World’s Fair in Paris. “Guernica” was his response. The Spanish painter had been at the height of his artistic career and living in Paris when Nationalists bombed the Basque town earlier that year.

Professor Suzanne Blier explains the Picasso installation.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“It’s an incredibly timely exhibit,” said Blier, Allen Whitehill Clowes Professor of Fine Arts and of African and African American Studies. “We’re dealing with fascism and horrendous bombings around the world. This painting reminds us of the importance of art in the world today and of the role artists can play when they engage with the world around them.”

Drawings, etchings, and lithographs in the exhibit show Picasso’s explorations with assorted styles, including cubism, one of the most important art movements of the 20th century, which he founded with French painter Georges Braque. The works on display are part of the museums’ collection.

“They represent such a broad range of examples of Picasso over his long career,” said Blier. “It’s rare that you get to see this amount of diversity of what he put together. It is a remarkable example of what an incredibly brilliant, striking, innovative artist he was.”

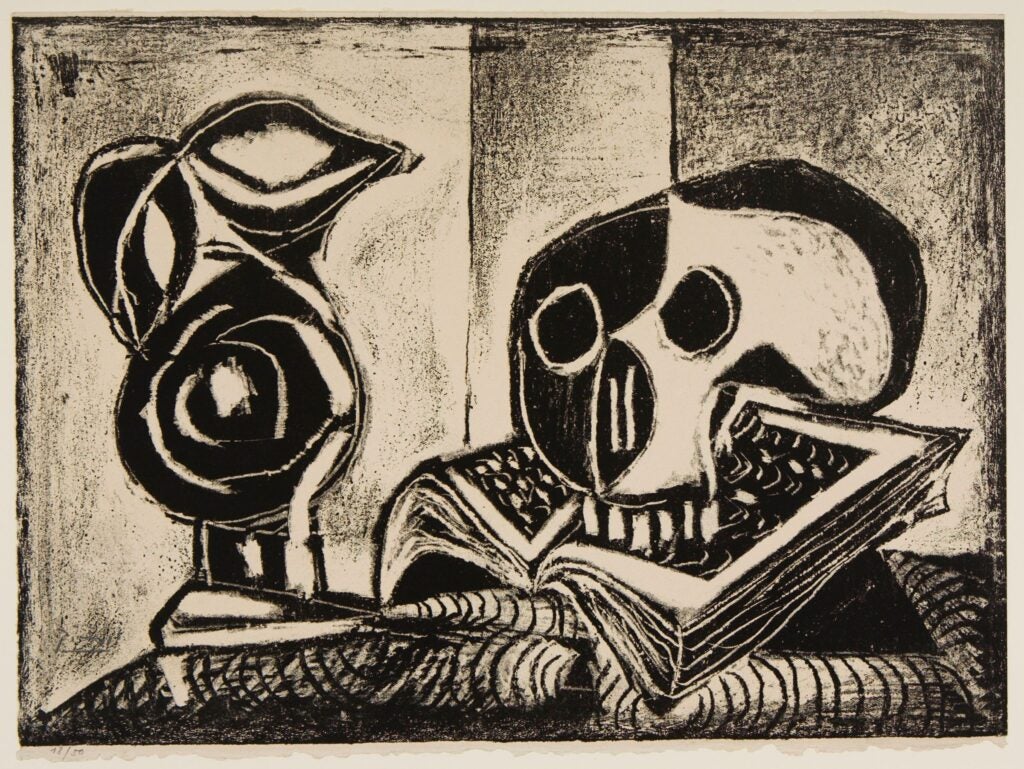

The exhibit showcases Picasso’s finest drawings of the Minotaur and fauns, bulls and matadors, and human and goat skulls. There are realistic renderings of human bodies and mother and child, and striking cubist paintings such as “Lady with Guitar” and “Pierrot and Red Harlequin.”

The drawings show Picasso’s evolution from a draftsman of realistic images to one of the greatest artistic innovators of the past century, said Joachim Homann, the Maida and George Abrams Curator of Drawings.

“Drawing has been a major tool for artistic innovation since the 14th and 15th century,” said Homann. “For 500 years, people have been drawing, but Picasso is taking it to a totally different level. For Picasso, drawing was the medium to come to terms with the essence of his art. And what he found was so radically different from what anybody else had seen before.”

“Man with a Pipe” exemplifies Picasso’s cubist innovation, said Homann. “You just stand in front of it and scratch your head, where is the man, where’s the pipe?” said Homann. “With cubism, Picasso found a completely new way of understanding how visual language operates. And many people throughout the 20th century realized that Picasso had delivered something that they could build on.”

The Harvard Art Museums own nearly 300 works by Picasso, and seeing them is a rare opportunity, said Laura Muir, director of academic and public programs, division head, and Louis Miller Thayer Research Curator.

“These works are light-sensitive, so we can’t show them very often,” said Muir. “Once they’re shown, they must rest for several years before our conservators will allow us to show them again. This is really a special opportunity for our audiences to see these rare and important works by Picasso.”

“The Black Pitcher and the Head of Death.”

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gray Collection of Engravings Fund

The exhibit also highlights the ways in which the museum can serve professors and students with installations that complement Harvard courses, but also benefit a general audience. “The museum has had a long history of teaching with objects,” said Megan Schwenke, senior archivist/records manager. “It was true in 1941 and it is still true today.”

Included in the exhibit is an essay by Harvard fine arts Professor Benjamin Rowland, who used “Guernica” in his 1941 class. “Instead of giving a realistic description of an actual air-raid, the artist has endeavored to imply the chaos and shock of disaster in such psychological terms,” he wrote. “These figures are badly drawn, of likeness to real anatomy is our only criterion. They are Picasso’s creations, his imagining of a new anatomy calculated by its pitiless caricature of human beauty to suggest the mental and physical disintegration and terror of people dying under the bombs.”

Rowland’s essay, Blier said, provides the context of how the painting was received in its early years and has since become one of the 20th century’s most powerful anti-war symbols. “You look at ‘Guernica’ today and you see how bold and modern it is, even in the 2020s. But this was nearly 100 years ago — the boldness of his characterization, away from naturalism, would have been even more startling then.”

Printed in banner form, the painting “is still carried around in Spain and other parts of the world to protest wars and as a powerful political symbol of people’s rights,” Blier said.

The professor will discuss Picasso’s engagement with warfare and revolution in a gallery talk on March 26.