Theda Skocpol (left) and Lainey Newman, authors of “Rust Belt Union Blues.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Why so many blue-collar workers drifted away from Democratic Party

New book puts mid-century unions at center of Rust Belt identity, social life. Shifting economy splintered community, fostered disillusionment.

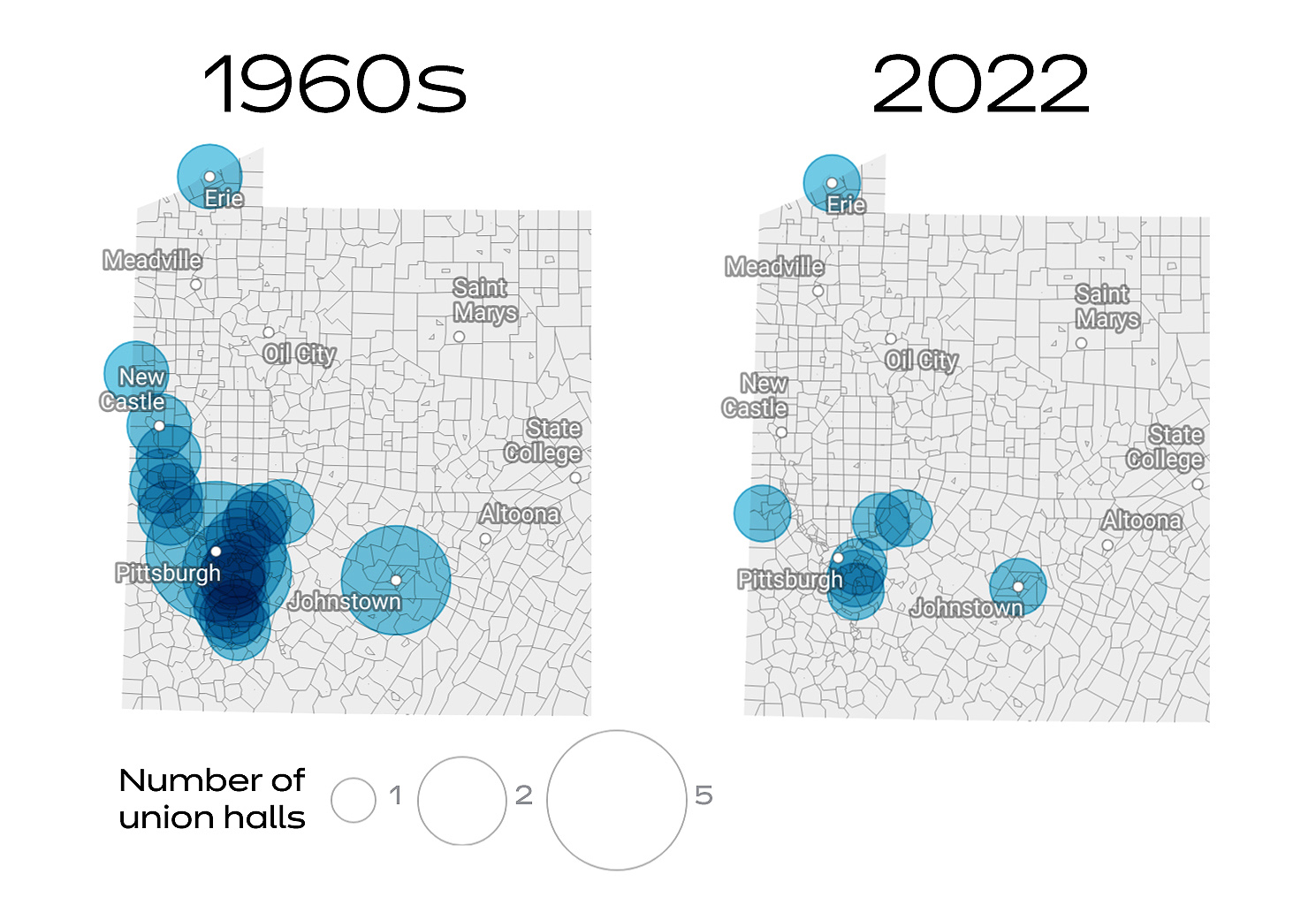

There were at least 37 United Steelworker halls in western Pennsylvania at one point in the 1960s.

“Some of them were quite beautiful,” said recent graduate Lainey Newman ’21, co-author of the newly released “Rust Belt Union Blues: Why Working-Class Voters are Turning Away from the Democratic Party.” One of the most impressive was in downtown Aliquippa, a two-story former bank in Classical Revival style. Others featured airy banquet halls or cozy club rooms.

An expansion of her senior thesis, Newman’s book focuses especially on western Pennsylvania in capturing the shifting sense of belonging — both politically and socially — for the all-American union man amid an economy growing less industrial and more global. The book, which places mid-century unions at the heart of Rust Belt identity and community life, was written in partnership with Newman’s thesis adviser Theda Skocpol, the Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology and one of the country’s foremost experts on fraternal groups and civic organizations across U.S. history.

“I am a Skocpolian student,” said Newman, who picked up quickly on the social centrality of organized labor when she started interviewing retired steelworkers and digging into archival materials, including the Aliquippa Steelworker newsletter from the 1960s and ’70s. “I do believe that the organizations people are a part of really influence who they are.”

United Steelworkers halls in W. Pennsylvania 1960s vs. today

Of 37 USW halls in the region in the 1960s, eight survived in 2022.

Source: “Rust Belt Union Blues: Why Working-Class Voters are Turning Away from the Democratic Party” by Lainey Newman and Theda Skocpol

As her research progressed, Newman came to understand the depth of that insight. Most of the scholarship on unions focused on the political and economic implications of membership. “It became clear to me that unions meant a lot more than just representing these metric-based interests,” said Newman, a Pittsburgh native who grew up with members of the United Auto Workers, or UAW, in her extended family.

“Union men were united by shared commitments to one another, their history, and their industry or trade,” Newman and Skocpol wrote. The union halls of Steel Country then housed meetings of scout troops and alcohol support groups. They hosted everything from big family weddings to sprawling sports leagues. One interviewee told Newman of a far-flung hall outfitted with its own basketball court.

As for matters of diversity, the authors stressed that the Steelworkers and other blue-collar unions made more attempts than many other mid-century institutions at welcoming women and nonwhite members into their overwhelmingly white “brotherhoods.” Also cited in the book was scholarship suggesting union membership reduced racial resentment among white workers.

The rank-and-file were not necessarily crazy about the union’s politicking, as the authors discovered from retiree interviews and a 1955 USW survey. Nevertheless, members supported Democratic candidates because they saw themselves as part of a working-class coalition. “Voting for Democrats and backing the party’s policy goals were part of a ‘who you were’ and even a matter of loyalty to one’s coworkers and friends,” the authors wrote.

Investments in local unity were one of the first things unions cut when plants started to close in the 1970s and ’80s. According to the book, only eight of the USW locals in western Pennsylvania with buildings in the 1960s still operate local union halls today. That stately outpost in Aliquippa, for example, is vacant. It was recently listed for sale at $450,000.

Liberals and pundits like to wonder why blue-collar workers keep voting “against their own economic self-interest,” the authors wrote, but this is the wrong framing entirely.

Meanwhile, workers realized their unions couldn’t protect them from job loss. As a result, Newman and Skocpol wrote, allegiances started to shift in favor of the steel mills and other large employers. Further dampening after-hours union activities were broader social changes including ever-lengthening commutes as plants closed and new family arrangements, with women increasingly entering the labor force and men picking up more of the load at home.

This shift was evident from interviews and the nontraditional fieldwork Newman conducted during the pandemic in the parking lots of three facilities, including the U.S. Steel Edgar Thomson Plant in Braddock, Pennsylvania. “It’s clear people are coming from all over,” noted Newman, who recorded license plates from Ohio and West Virginia. She also interviewed men and women alike who had to rush home from work for daycare or school pickup.

Also clear in her parking-lot research was a conservative bent to worker bumper stickers. The most common themes concerned gun rights and GOP candidates. “I also saw a lot of Thin Blue Line bumper stickers, supporting the police, and then a couple of Confederate flags,” said Newman, now a Harvard Law School student eyeing a legal career in worker protection. Just 12 percent of the stickers she recorded had union-related messaging. Only 1 percent proclaimed support for Democratic candidates.

As the union’s social role eroded, the book observed, workers filled the void with other, often more conservative groups. For instance many flocked to gun clubs, often expressly affiliated with the NRA. Socializing in such right-leaning organizations may seem to outsiders the opposite of hanging out at Democratic-affiliated union halls, but many locals would disagree. As one retired mine inspector noted of his neighbors: “I don’t think their worldview has changed that much over the last 50 years. They see themselves as being left out and looked down upon. … When unions started to fade, you started to get that line from the NRA instead.”

As the union’s social role eroded, workers filled the void with other, often more conservative groups.

Liberals and pundits like to wonder why blue-collar workers keep voting “against their own economic self-interest,” the authors wrote, but this is the wrong framing entirely. As Skocpol put it: “It’s about building relationships” and community.

The book’s final chapter floats a few ideas for re-establishing strong union ties and perhaps even support for pro-worker Democrats, including new financial investments in community-building and a focus on events centered on children.

Another of the book’s contributions is a hypothesis concerning the divergent paths of industrial unions like the USW and skill-based trade unions. The former has survived declining membership by diversifying into other professions, a fact perfectly demonstrated by Newman’s own membership in the UAW as a graduate student. The authors argue that this has diminished the sense of unity based on occupational pride and shared commitment for members working in a single industry.

In contrast, the authors find evidence that trade unions have done a better job at maintaining community and occupational pride. “Everyone in the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers has these specific skills, and it takes a lot of training to get to the point where you are admitted,” said Newman, who found that some interviewees likened their trade unions to medieval craft guilds.

It also helps that trade unions act as hiring halls, doling out contracts and therefore retaining greater member loyalty. As a result, the authors suggested, members of the IBEW and similar craft-based unions may be maintaining closer ties with the Democratic Party. They hope scholars who read the book will be inspired to gather new evidence that tests the theory.

“Notice the irony,” said Skocpol, who grew up amid the industrial plants of Greater Detroit. “Historically, the trades were seen as a bastion of conservatism — and for good reason, because they were often quite racially and ethnically exclusive. They may still be to some degree, but they’ve changed with the rest of America.”