Harvard’s William G. Kaelin Jr. receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Dec, 10, 2019. Michael Kremer, who won the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences, is pictured standing (left).

Photo by N. Adachi © Nobel Media AB.

Did winning the Nobel change your life?

Harvard laureates say it gave bully pulpit, brought invitations to speak (sometimes on subjects they know nothing about), meet kings (and play poker with Steve Martin)

The first week of every October committees in Sweden and Norway announce the winners of the Nobel Prize to celebrate outstanding contributions to physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature, economics, and peace.

Fifty Harvard faculty have received this prestigious award while working at the University. Economist Amartya Sen was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1998, when he was at Trinity College in the U.K.

We asked seven of these laureates how winning changed their lives, what influence it had on their work, and how they dealt with the sudden notoriety.

“I was recently knighted; that’s something that obviously wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t won the prize.”

Harvard file photo

Oliver Hart

Lewis P. and Linda L. Geyser University Professor

Winner of the 2016 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences, together with Bengt R. Holmström, for “their contributions to contract theory.”

“Did my life change after the Nobel? It surely did. You get an enormous amount of attention. I was the kind of academic who was writing for many other academics, so I wasn’t getting much attention in the outside world before the Nobel. Initially, everyone wants to find out what you think about a number of things because there is this idea that maybe this person has the answer to all the questions, and very soon they figure out you don’t [laughter], and the attention diminishes. But it still stays at a significantly higher level than before. It’s a big change.

“Since winning the Nobel, I have been working on two areas. The first was a continuation of the work for which I won the prize, which is about contracts, particularly about contractual incompleteness and how people deal with the fact that any contract is going to have stuff left out of it. As a result of winning the prize, I got to know a legal practitioner based in Stockholm, with whom I started a collaboration, which was just pure serendipity, and it just wouldn’t have happened without the prize. The second is corporate social responsibility, which I’m very interested in, but that perhaps would have happened anyway.

“The Nobel is such a magical name and the fact that I’m a Nobel laureate seems to matter. But I would say after the first year, it’s back to normal with a few extra things. It mostly is business as usual.

“Unfortunately, contract theory has not become any more popular among graduate students just because of this prize. Initially, I received lots of requests from high school students wanting to be my research assistant and from journalists who want me to give my views about the U.S. economy or the Chinese economy. I always say the same thing, which is, ‘I’m the wrong person for that.’

“The other thing I didn’t anticipate was this feeling, and probably I’m not alone in sometimes thinking, ‘Why on earth did I win the Nobel? Did I deserve it?’ This kind of impostor syndrome, I certainly experienced, and still experience it. I felt more deserving before I won it than after [laughter]. That feeling was a bit of a surprise, but by and large, though, it’s been very positive, there’s no question about that. A surprising thing was that I was recently knighted; that’s something that obviously wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t won the prize.

“Some people ask what the secret to winning the Nobel is, and I’d say that the secret is to work hard, to produce good work, and not to think too much about it. To say the obvious, there’s a considerable amount of luck involved because there are many people who are worthy of it who don’t win it. I don’t think anybody’s aim should be to win the Nobel Prize. It certainly wasn’t my aim when I started out. I think the only thing you can really do is to do the research that interests you and to see where it goes.”

“I have always wanted to start a charity focused on children’s education and healthcare for the poor. The money I received from the Nobel Prize gave me the opportunity …”

Harvard file photo

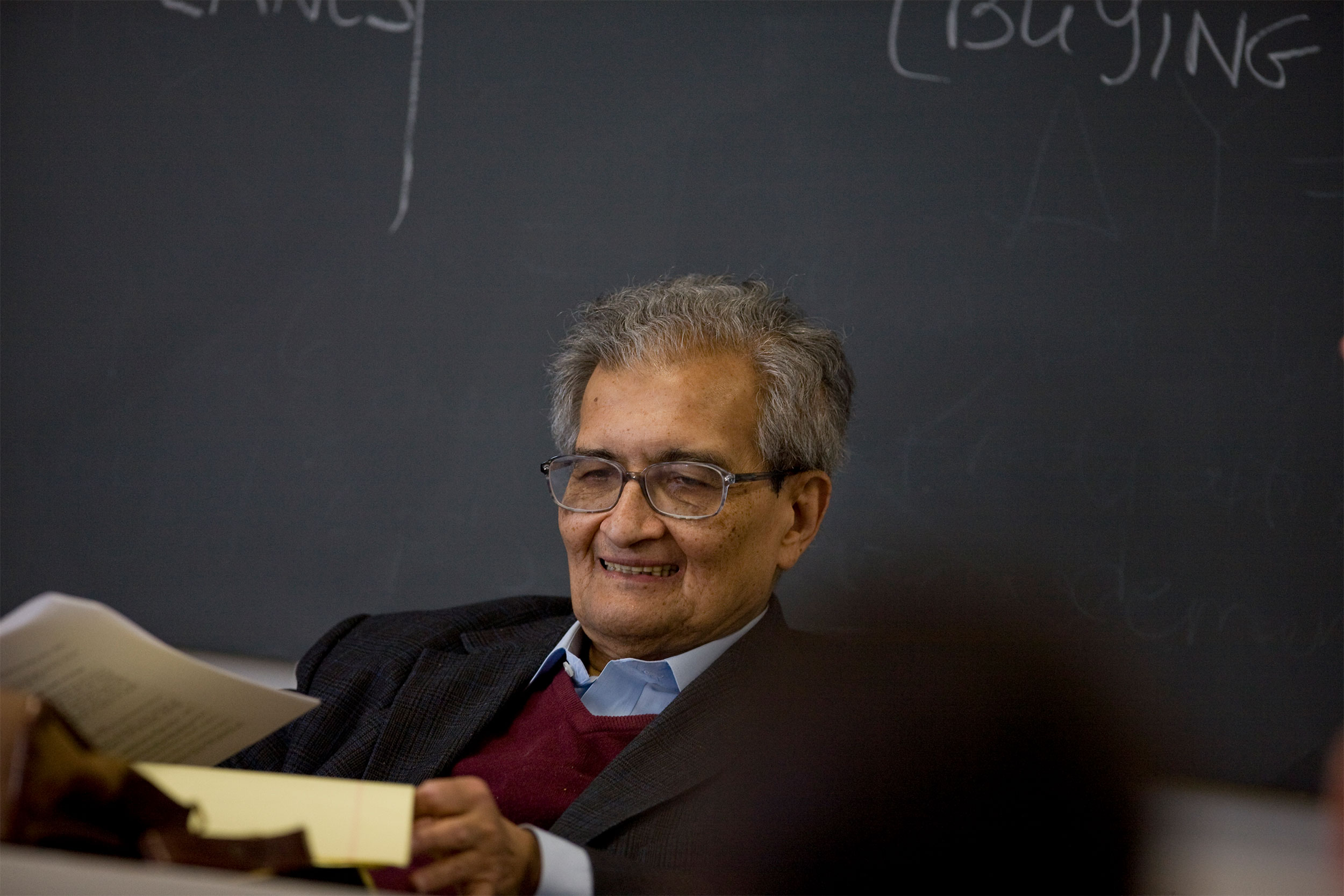

Amartya Sen

Thomas W. Lamont University Professor and Professor of Economics and Philosophy

Winner of the 1998 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences “for his contributions to welfare economics.”

“I can’t say that the Nobel Prize changed my life in a big way. Winning the Nobel in 1998 did not lead me into new directions in my research or have a gigantic effect in my career. I see the Nobel as one of many recognitions that exist to celebrate achievements in science, literature, and so on. After the Nobel, I continued to work on the issues that have always preoccupied me: the economics of poverty and human development.

“A positive effect of winning the Nobel Prize was that the subject of education and healthcare for the poor gained more attention and interest around the world. As for any negative effects, I can’t think of any, but I would have to say that the celebration tends to take a lot of your time; there are many social obligations, which can distract you from work. After I won the Nobel Prize, there was a lot of interest, particularly in India and Bangladesh, about me and my work, and many people kept reaching out to me to do interviews.

“I have always wanted to start a charity focused on children’s education and healthcare for the poor. The money I received from the Nobel Prize gave me the opportunity to start the Pratichi Trust in India. The trust is named after Pratichi, my ancestral home in Santiniketan, India, and what it does is to provide basic schooling and medical care for young children. The Nobel Prize allowed me to channel some resources to those causes I deeply care about.”

“There’s also been a fun side to the prize … As part of a fundraiser, I spent an evening once playing poker with comedian Steve Martin, who is a better player than me, even though I’m the game theorist.”

Harvard file photo

Eric S. Maskin ’72, Ph.D.’76

Adams University Professor

Winner of the 2007 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences, with Leonid Hurwicz and Roger B. Myerson, for “their work on mechanism design theory.”

“Did winning the prize change my life? Not my daily life, at least not on most days. I got into this line of work because I love research and teaching — and that’s what I mainly still do. My colleagues and students don’t care much that I won a prize, which was for work done many years ago. They’re more interested in my current thinking. So, if I make a claim about, say, income inequality in the class I’m teaching this term, I have to back it up with logic and evidence — argument by “authority” won’t do. Furthermore, I don’t think the prize has changed what I work on. But there’s little question that the prize has given me a wider audience. One area I’m interested in professionally and as an activist is election reform, i.e., improving the way we elect our political leaders. And, through my notoriety, I’ve had many chances to write op-eds on this for newspapers, give public lectures, testify before legislatures, serve on task forces, and help draft legislation. I especially like talking to students about what I do in the hope that some of them might get interested in learning more about it.

“There’s also been a fun side to the prize — I’ve talked to kings and queens, presidents and prime ministers, and many others I probably wouldn’t have met otherwise. I met the royal family of Sweden, of course; King Charles when he was the prince of Wales; the king of Jordan, whom I met at a climate change conference; the king of Thailand; and the king and queen of Spain. As part of a fundraiser, I spent an evening once playing poker with comedian Steve Martin, who is a better player than me, even though I’m the game theorist.

“Among the negative effects, there are too many distractions from teaching and research, and secondly, I’m being asked questions that I’m not qualified to answer because journalists think Nobelists know everything — and feeling the temptation to answer them anyway. For example, I get asked, ‘What is going to happen to the unemployment rate next year?’ Economic forecasting is not a strong aspect of economics, but I’m especially unqualified because that’s not something I studied. I’ll be asked questions such as: How should we resolve the tensions with China? Or, how do we end the war in Ukraine? There’s always a temptation to talk about stuff that you don’t know about. I think it’s better to resist that temptation, but it’s not always so easy.

“I have a son who is severely disabled from a brain injury when he was very little. He attended a wonderful school in Pennsylvania for disabled kids when he was of school age. I was very happy to be able to repay the support that they gave my son and the family by giving most of my prize winnings to them.”

“Being a Nobel laureate made it possible for me to be invited to present lectures at traditional Black colleges, like Fisk University, and inspire students to realize their potential.”

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Martin Karplus

Theodore William Richards Professor of Chemistry, Emeritus

Winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in chemistry, together with Michael Levitt and Arieh Warshel, for “the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems.”

“Being awarded the Nobel Prize certainly did change my life. However, as one Nobel laureate colleague said, I was lucky that it happened so late (I was 83 at the time) because he had found

it to be very disruptive to his day-to-day activities. I was fortunate that the changes the announcement brought were largely positive. I was able to continue my work, but it did not lead me to discover new directions in my research.

“It gave me the opportunity to reach a larger audience. Being a Nobel laureate made it possible for me to be invited to present lectures at traditional Black colleges, like Fisk University, and inspire students to realize their potential. I declined many invitations which came my way to give lectures on subjects about which I did not know anything.”

“Even now, nearly four decades later, I still receive invitations to give talks in countries near and far, as well as requests from postdocs from all over the world who want to do research in my group.”

Harvard file photo

Dudley Herschbach, Ph.D. ’58

Frank B. Baird, Jr. Professor of Science, Emeritus

Winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize in chemistry, jointly with Yuan T. Lee and John C. Polanyi, for “their contributions concerning the dynamics of chemical elementary processes.”

“The biggest change was that I was invited to give talks about my research all over the world, not just the U.S., Britain, and Germany. I gave talks in Egypt, Israel, Japan, China, and even Kuala Lumpur, among many other countries. Also, postdoctoral fellows from all over the world wrote to ask if they could join my research group at Harvard. Even now, nearly four decades later, I still receive invitations to give talks in countries near and far, as well as requests from postdocs from all over the world who want to do research in my group. I also continue to receive letters from young people who have read about me and my research. Often, they ask me to autograph photos of me they’ve found on the Internet. Usually, the photos were taken many years ago. These young scientists have no idea that I’m now 91 years old and no longer doing scientific research, but I always sign the photos and send them back. I want to do all I can to encourage young people to pursue science. It’s such an exciting world.

“After winning the prize, I continued to pursue my research in molecular beam chemistry. I could never have pursued my research without the benefit of generous grants, most of which were funded by the National Science Foundation. Scientific research is well-supported in our country, but the humanities are not. Thus, I donated my prize winnings to organizations in the humanities. Most were classical music organizations. All members of our family and most of our friends benefited from classical music performances, both as auditors and performers. I also funded an important project with my Nobel Prize winnings. I commissioned the American artist Patricia Watwood to paint a portrait of the great Harvard astronomer Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. Among other significant contributions to astronomy, Payne-Gaposchkin discovered that hydrogen is millions of times more abundant than any other element in the universe. I donated Watwood’s portrait to Harvard. It now hangs in the Faculty Room in University Hall. With Watwood’s permission, I paid for technicians at the Harvard Art Museum to make a copy of Payne-Gaposchkin’s portrait. The copy was installed at the Harvard College Observatory where Cecilia carried out her brilliant research.”

“I knew objectively the discovery we made in the year 2000 was the kind of discovery that sometimes wins prizes, but I always remind students that a prize is a tribute to nature, not a tribute to us.”

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

William G. Kaelin Jr., M.D.

Professor in the Department of Medicine at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, and Associate Director, Basic Science, for the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center

Winner of the 2019 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, with Sir Peter J. Ratcliffe and Gregg L. Semenza, “for their discoveries of how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability.”

“I’ve heard stories of Nobel laureates who said their lives were changed after winning the prize, but I have tried to stay focused on my work. My mentor David Livingston was a physician scientist at Harvard for many years, and he used to say that a good scientist should always think that the most important thing they’re ever going to do lies ahead of them. I try to adhere to that advice. In addition, as a physician scientist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, I see patients in the waiting areas every day. I certainly know we have a lot more work to do collectively to try to control this disease better. That keeps me grounded. Finally, COVID struck several months after I got the prize. I like to think I would not have gone off onto the banquet circuit for a year, but I had no choice; like everyone else, I was just trying to stay at home and survive COVID. In any event, I don’t think winning the Nobel Prize changed my life all that much.

“Among the positive aspects, one of the wonderful things is being able to share it with all the people in your life who made it possible to win the Nobel Prize. It’s been wonderful to be able to share this with my family, my colleagues, my mentors, and my trainees. Sadly, you might know that my late wife died in 2015. It was extremely sad that I couldn’t share it with her because she was instrumental in everything I did, professionally. But it was wonderful to share it with my two children. I used a fair amount of the prize money to have two white-tie formal parties in Newport, one for my family and friends, and the other for my past and present trainees. It was my way to say thank you to the people in my life who helped make it possible. Secondly, because of my slightly different stature in the field, I can hopefully add my voice to the many voices trying to champion science and investments in science. I have a new voice now, if you will, because people listen to me in a way that they wouldn’t have listened to perhaps before.

“I had been properly warned ahead of time about potential negatives. I was warned that just because you win the Nobel Prize, you don’t suddenly become an expert on Middle East peace, on saving the whales, and all sorts of issues. I’m very careful about what causes I will lend my name to, or what petitions I will sign. If you’re not careful, you could spend a lot of time on the road giving talks, meeting people, going to banquets, and I think I’ve managed that well. My primary responsibility is to the people who’ve trusted their scientific training to me and my laboratory. I have to make sure I’m available for those people first.

“We were very fortunate to have won some of the pre-Nobel Prizes, such as the Lasker and the Gairdner. I knew objectively the discovery we made in the year 2000 was the kind of discovery that sometimes wins prizes, but I always remind students that a prize is a tribute to nature, not a tribute to us. A Nobel laureate used to say that most scientific prizes say more about the discovery than the discoverer. We stumbled upon something nature had done that was beautiful and elegant and unexpected.

“I wasn’t completely surprised that I won the Nobel Prize before I died. What surprised me is how different this prize feels, compared to all the other prizes, and how it has taken on an almost mythological proportion. I like to think I’m an analytical, rational person who can understand and explain this, but I can’t completely understand it. Part of it is its long history, and it’s linked to the Swedish royal family, and it doesn’t hurt that Sweden is thought of as being neutral and fair. But I can also see the great care that goes into every aspect of the celebrations in Stockholm; they have done a fantastic job over the years to make this prize feel very special.

“Like many other laureates, I’m often asked, ‘quote-unquote,’ what’s the secret of winning a Nobel Prize? The answer I heard another laureate gave, which I would have given as well, was that the secret is: Don’t think about prizes. If you set out to win prizes, statistically, you’re going to wind up disappointed, but if you set out to do good science, you do your job well, and you’re extremely lucky, you may occasionally win a prize. I tried to remind people, first of all, that the real prize is doing something that you enjoy so much that you feel guilty that people pay you for it, which is the way I feel. The other prize is seeing something nature had done that is so beautiful and elegant, and appreciating that you’re the first person in the history of mankind who has understood it. Another prize, so to speak, is if your discovery occasionally enables the development of a new medical treatment. Already, our work led to some advancements, both in the treatment of anemia and kidney cancer. That’s far more meaningful, and far more objective than a bunch of people around the table deciding to put a blue ribbon on your work. I’m glad that we celebrate science with the Nobel Prize, but I wouldn’t want to see it become a preoccupation for anybody. The focus should be on enjoying one’s work and hopefully doing it well and trying to make contributions.”

“One area where I feel the prize allowed my research to have more impact is market-shaping approaches to encourage investments in innovation …”

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Michael Kremer, Ph.D.’92

At the time of the award, Kremer was working at Harvard. Now, he is at the University of Chicago.

Winner of the 2019 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences, with Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, for “their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty.”

“I’m heartened by the increased recognition that the 2019 Nobel Prize has brought to the field of development economics. More students are keen on working in development economics, and universities have been expanding their development economics programs and allocating greater resources to research within this field. Harvard has many wonderful graduate students and some great faculty in this area. Unfortunately, it has lost some people as well, and I hope it will be able to rebuild soon.

“One area where I feel the prize allowed my research to have more impact is market-shaping approaches to encourage investments in innovation in ways that also broaden access to the innovations once developed. I had earlier proposed the concept of advance market commitments to incentivize the development and accessibility of vaccines targeting diseases that primarily affect low- and middle-income countries. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several governments and international agencies requested support to explore contract structuring to expedite vaccine development. My colleagues and I recommended issuing contracts to establish vaccine manufacturing capacity ahead of clinical trials in the United States and the United Kingdom, which consequently obtained access to vaccines relatively quickly. This approach was adopted but unfortunately not by many other countries.

“Currently, I serve as the chair of a commission focused on innovation in climate change, food security, and agriculture. Many innovations in climate adaptation and mitigation in agriculture have potentially high social benefits, but don’t receive adequate investment due to limited commercial incentives. For example, providing high-quality weather forecasts to farmers in low- and middle-income countries could significantly bolster their resilience to climate change. However, under existing institutions, it would be difficult for private firms to recoup investments in this area. The Innovation Commission is working to identify mechanisms to overcome such barriers and facilitate the scaling of effective innovations.

“We are also exploring market-shaping institutions to stimulate innovation in climate change solutions. Cement accounts for about 7 percent of emissions globally and half of cement is purchased by the government. Governments could spur the development of various promising green cement technologies by announcing that they would account for the social cost of emissions from cement used in construction when evaluating bids for the construction of public infrastructure. We are getting substantial interest in these ideas from policymakers, and I think that is certainly due in large part to the Nobel Prize.”