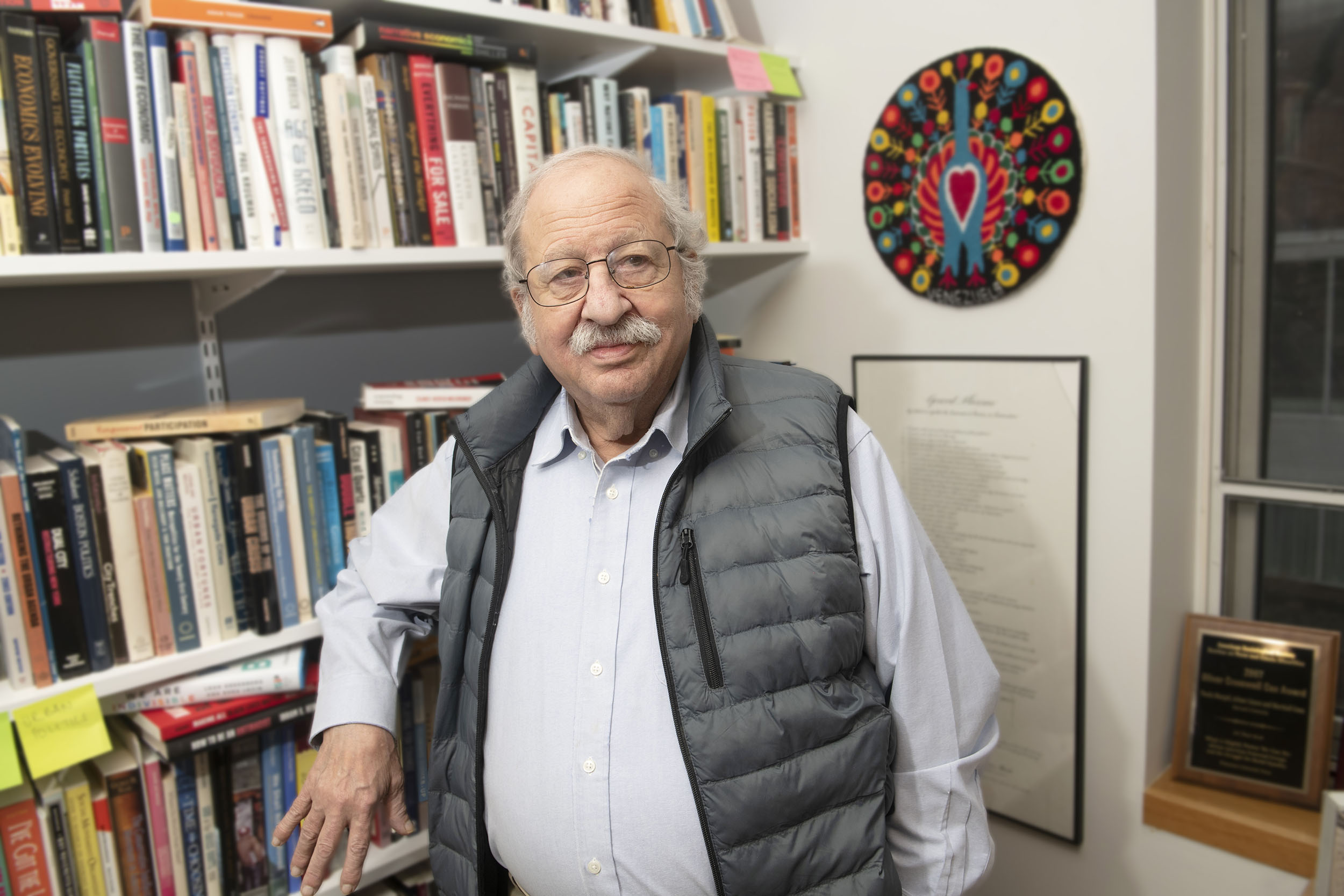

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘What is compelling to do right now?’

Marshall Ganz started at Harvard but took some time off — about three decades — to become Civil Rights, labor, political organizer, and finally scholar, mentor

Marshall Ganz was a junior at Harvard College, still struggling to figure out what he wanted to study and do with his life. Then came that difficult, dangerous — and exhilarating — Freedom Summer of 1964 working with Civil Rights activists under the hot Mississippi sun to register Black voters, even being arrested twice and thrown in jail. His path became clear.

“There’s a difference between finding a calling and a career,” said Ganz, Rita E. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Leadership, Organizing, and Civil Society at Harvard Kennedy School, of his experience. “How that was going to play out, and if it was going to sustain [me], who knows? The choices I made were always, ‘What is compelling to do right now?’”

“There’s a difference between finding a calling and a career.”

Marshall Ganz

That galvanizing summer led to an almost 30-year break from the College for Ganz, who worked as an organizer with the United Farm Workers, other grassroots movements, and political campaigns before returning to Cambridge to finish his undergraduate and graduate degrees. While hardly a straight line, Ganz’s career trajectory from activist to organized-labor scholar follows a kind of logic rooted in his childhood as the son of a rabbi and a teacher who imparted lasting lessons about race, equality, and social justice.

“I think of him as the Rabbi of Organizing,” said Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology, who was Ganz’s Ph.D. adviser and is now a colleague and friend.

“Marshall has helped to train many of the organizers who have worked for some of the major political campaigns. [He] teaches people how to relate to others, how to build organizations, which doesn’t come naturally to today’s young, and how to harness moral passion for collective purpose.”

Ganz’s mother, who was raised in Virginia, studied philosophy and psychology at the College of William & Mary. His father enlisted in the U.S. Army as a chaplain in 1944, a year after Ganz was born and the last year of World War II.

The young rabbi was sent to Germany to serve American GIs, but, after the end of the war, much of his work involved Holocaust survivors. He was joined in Germany by his family in 1946, and they lived there for three years.

It was a difficult time that left a lasting impression on Ganz, whose fifth birthday party was held in a displaced persons camp for children who’d been orphaned in the war. He was to give gifts rather than receive them.

“My parents interpreted the Holocaust to me as not being simply about anti-Semitism, but about racism very explicitly,” said Ganz. “My mom, coming from the South, was so clear about it.”

After rabbinical posts in Washington, D.C., and then, Fresno, California, the family settled farther south in Bakersfield, where Ganz lived through high school. A hot, dry city of farms and oil rigs (and “outlaw” country music superstars Merle Haggard and Buck Owens), Bakersfield was not where a teenager who admired the 1950s Beat Generation writers in San Francisco saw himself long-term. Despite having a racially and ethnically diverse population, Ganz said, “It remains probably one of the most racist cities in California.”

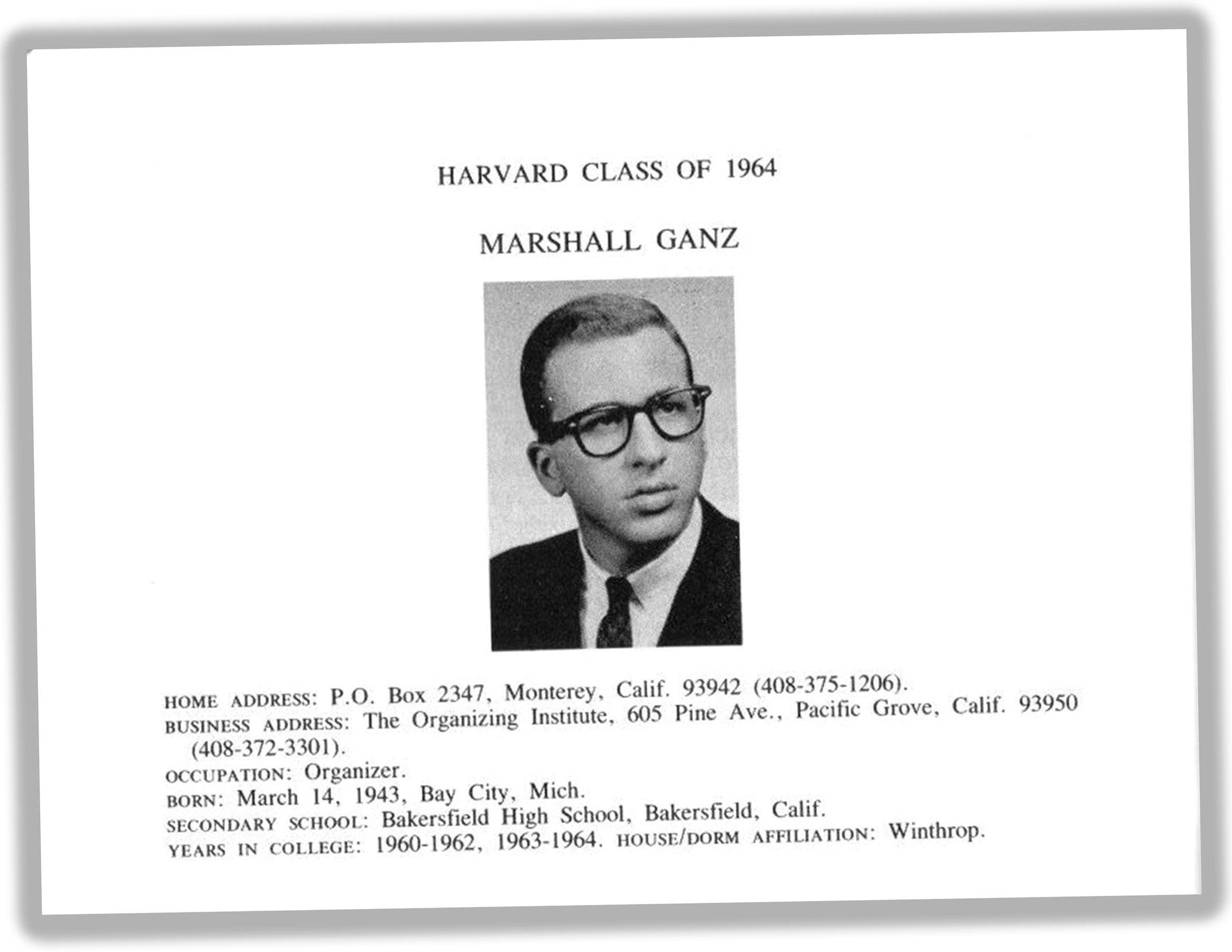

At his mother’s urging, he set his sights on Harvard College despite never having been to Boston.

“I only applied here, which was more stupid than arrogant,” he said. Ganz was driving a delivery van for a Chinese restaurant part-time as a high school senior when he got the letter that he had gotten in and more importantly, received a scholarship. “Otherwise, there’s no way I could have come.”

Ganz arrived at Matthews Hall as a first-year in the fall of 1960, just as the closely contested presidential race between Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts was reaching a crescendo.

Just weeks after Kennedy’s victory, the new president-elect visited Harvard Yard to celebrate and was later joined by faculty and administrators including economist John Kenneth Galbraith and McGeorge Bundy, then dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

“It felt like, all of the sudden, you’re in this place where history is happening,” Ganz said. “This proximity to history was really powerful.”

That excitement was tempered, however, by the trouble Ganz was having finding his social and intellectual niche.

“There were all these guys in tweed jackets that went to schools that I had never heard of — Andover, Exeter — and they all seemed to know the faculty by their first name,” he said.

Ganz had hoped to join a new social studies program started by the renowned political scientist Stanley Hoffmann. “But I didn’t get into social studies, and I didn’t know quite what to do,” he said of his sophomore year. So, he studied government but found it unengaging.

“I was interested in the relationship [between] culture and politics. That’s what I was really drawn to — but that wasn’t a department,” he said.

Ganz took off the 1962-1963 academic year to live in Berkeley, California, where his girlfriend was studying theater. He got a day job at an insurance company, audited night classes at the University of California, explored the city’s folk and rock music scene, and thought about what he wanted to do with his life.

A series of events in 1963 started bringing things into focus for Ganz. It began with the assassination of NAACP activist Medgar Evers by a white supremacist in June. Later that summer 250,000 people joined Martin Luther King Jr. for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In September the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four young Black girls.

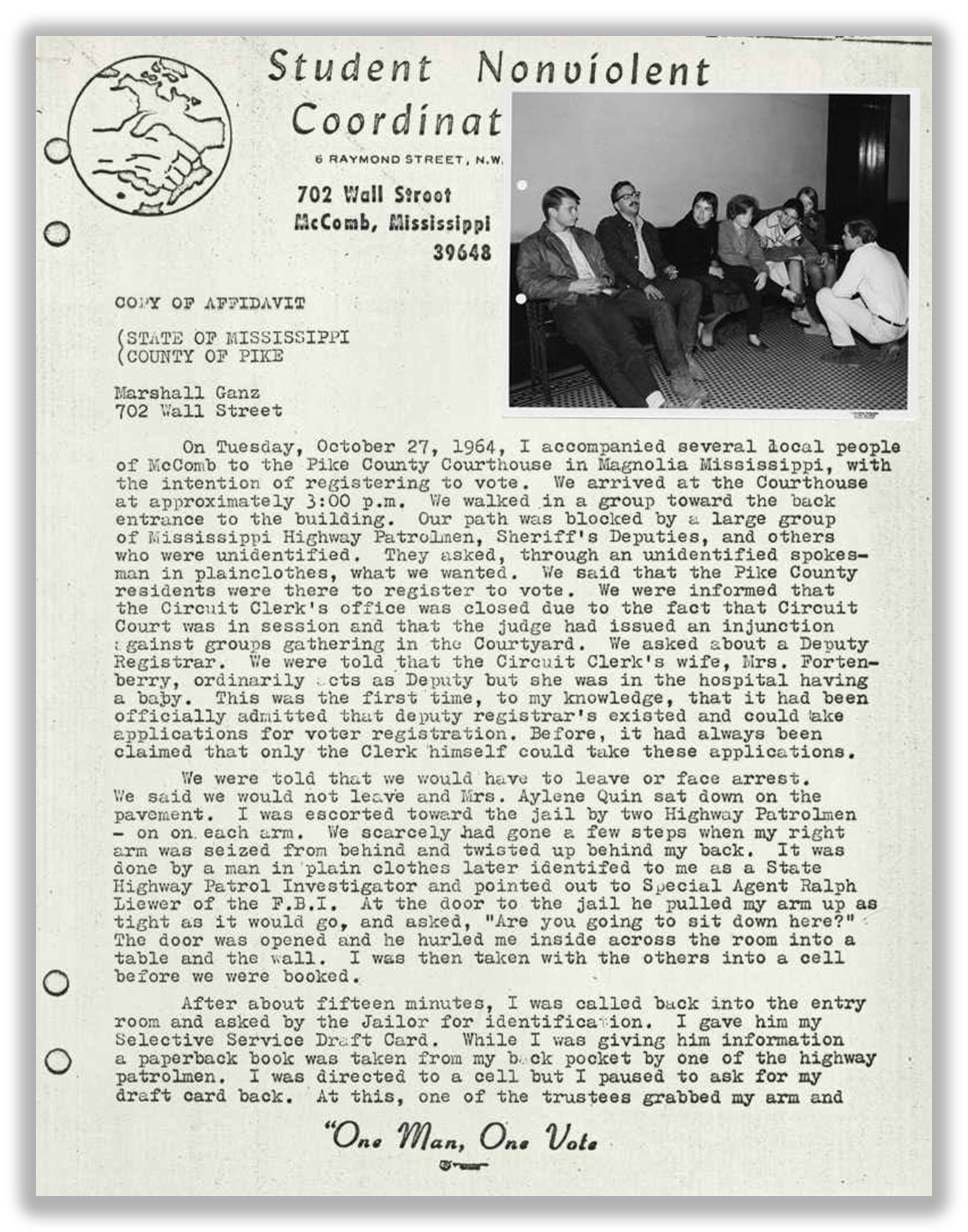

Ganz returned to Harvard that fall, changing his concentration to History and Literature (he planned to write about Bertolt Brecht, the Berliner Ensemble, and Weimar Germany). Soon after he was recruited by Civil Rights activist Dottie Zellner to join the Friends of SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), operating from an office in the basement of Epworth Methodist Church near the Law School.

The SNCC was a group of young, courageous, mostly Black college students who organized peaceful protests and voter drives in Southern states. It was chaired by John Lewis, later a Democratic congressman from Georgia. Through his involvement with the SNCC Ganz began spending time with like-minded spirits in Cambridge and various organizers.

Ganz and others were invited to visit SNCC headquarters in Atlanta so they could return to organize pressure on Harvard which, it turned out, owned stock in Mississippi Power and Light.

“We didn’t win that one,” he said, “but the more I did, the more committed I became.”

That spring a coalition of Civil Rights groups, led by the SNCC, decided to launch a Freedom Summer project to support the work of Black organizers and community leaders in Mississippi. With those activists under constant attack and arrest, the SNCC strategized that Southern law enforcement might think twice about going after students from elite colleges and universities in the North.

Volunteers, including Ganz, were repeatedly arrested, harassed, or beaten. Activists Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner were kidnapped and murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan in rural Mississippi in June.

Ganz’s mother was torn about her son’s decision to journey South. While she firmly agreed with the stand he was taking, she feared for his safety. Ganz was headed to McComb, Mississippi, in Pike County, a hotspot of Klan violence. More than a dozen churches and other buildings had been bombed in spring and summer of 1964, and a house where 10 SNCC volunteers were staying was dynamited.

“And so, for her, I was doing a good thing,” said Ganz. “But she was scared and probably should have been scared. ‘You can help more by becoming a lawyer’ — that was kind of the line. But I said, ‘No, I have to do this now.’” She would soon become an organizer of a Friends of SNCC group in Bakersfield.

The visiting students helped efforts to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as part of a plan to unseat and replace the segregated state party with their members at the national convention in Atlantic City.

The plans were thwarted by President Lyndon Johnson, who was running for re-election, but the groundwork was laid for another round of organizing, culminating with the Selma to Montgomery March and, finally, passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“It’s really there that I found what was going to be my calling for the rest of my life,” said Ganz. “With all due respect to Harvard, my education about race, power, and politics in America began there.”

That August, Ganz wrote to Winthrop House administrators telling them he wouldn’t return for his senior year.

“I was participating in the work of enabling people to find their voice, their solidarity, and their courage to build their own power to challenge the racist power being exercised over them. It was real. It was about deep change. And it was working,” he said. “I’m going to go back and write about Weimar Germany? Why would I do that?”

Ganz remained in the South with SNCC for another year before returning home to Bakersfield, where he met Cesar Chavez and others who had formed a Farm Workers Association in 1962 to organize Mexican immigrants employed in fields and orchards of California. In 1965, the group would launch what would become a landmark five-year strike of Mexican and Filipino pickers known as the Delano Grape Strike.

“I had grown up in the midst of the farmworker world, but I hadn’t seen it, until I returned with ‘Mississippi Eyes.’ Here was another community of people of color, also without political rights, also without protection of the labor laws from which they were excluded, and California with its own rich history of racial domination beginning with the Native people, the Chinese, the Japanese, the Filipinos, and, of course, the Mexicans. So, I learned Mississippi was not an exception to America. It was an example of the America we needed to change.”

A United Farm Workers rally in Salinas, California, 1970, with Marshall Ganz (glasses), AFL-CIO Director of Organization Bill Kircher (in plaid jacket), Cesar Chavez, and others.

Bob Fitch photography archive, © Stanford University Libraries

Over his 16 years with Chavez, Ganz wore many hats, becoming director of organizing, serving on the national executive board, organizing Canadians to boycott California grapes. His first political campaign work involved organizing in East Los Angeles, a predominantly Mexican American area, for a get-out-the-vote effort for Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in the June 1968 California primary. “Although he won based on the Latino votes we turned out, we lost him, tragically,” on the night of the election victory.

Skocpol said Ganz “has transformed Harvard’s offerings and continue[s] to have an absolutely galvanizing and inspiring impact on undergraduates and graduates who are called to this kind of leadership.”

He also built the global Leading Change Network of organizers, educators, and collaborators committed to developing leadership, building community with that leadership, and transforming the resources of those communities into the power to achieve needed change. In all, some 6,000 students from around the world have been introduced to the practice of organizing, gone on to introduce others to organizing, and developed grass-roots organization in places as distinct as Jordan, Japan, Canada, Mexico, Denmark, and Pakistan.

Indeed, Ganz’s expertise in movement organizing led to calls from political groups and candidates looking for help, beginning in the 1970s and ’80s, with California political leaders including Jerry Brown, Alan Cranston, and Nancy Pelosi.

After a break while working on his Ph.D., Ganz was asked to train young people working on Vermont Gov. Howard Dean’s presidential campaign in New Hampshire. Although Dean lost in the 2004 balloting, the organization turned New Hampshire “blue” in the fall with a team that included members who became key organizers in the 2007-08 Obama campaign. Ganz’s work with them turned out to be an innovative, successful grass-roots campaign that played a key role in that historic election.

“I came back here for a year and then it turned into two, and then it turned into a Ph.D., and then it turned into teaching here. None of that was in the plan.”

Marshall Ganz

Ganz had returned to the College in 1991 for his senior year at age 47, but hadn’t intended to stay to get an M.P.A. (1993) or a Ph.D. in sociology (2000), much less teach after that.

“I came back here for a year and then it turned into two, and then it turned into a Ph.D., and then it turned into teaching here,” he said. “None of that was in the plan.”

In fact, Ganz never had a blueprint for how his life would unfold after leaving Harvard, which he believes was key. “I didn’t experience life as having a plan that you then enact,” he said.

Though he found his passion while still in College, many students are still searching or wondering whether the path they’re now on is the right one. Ganz said he encourages students to ask themselves the questions he asked himself — and to have faith in themselves.

“That’s a discovery process,” he said. “And boy, that’s what I found in Mississippi.”