Start of new era for Alzheimer’s treatment

NIH via AP

Expert discusses recent lecanemab trial, why it appears to offer hope for those with deadly disease

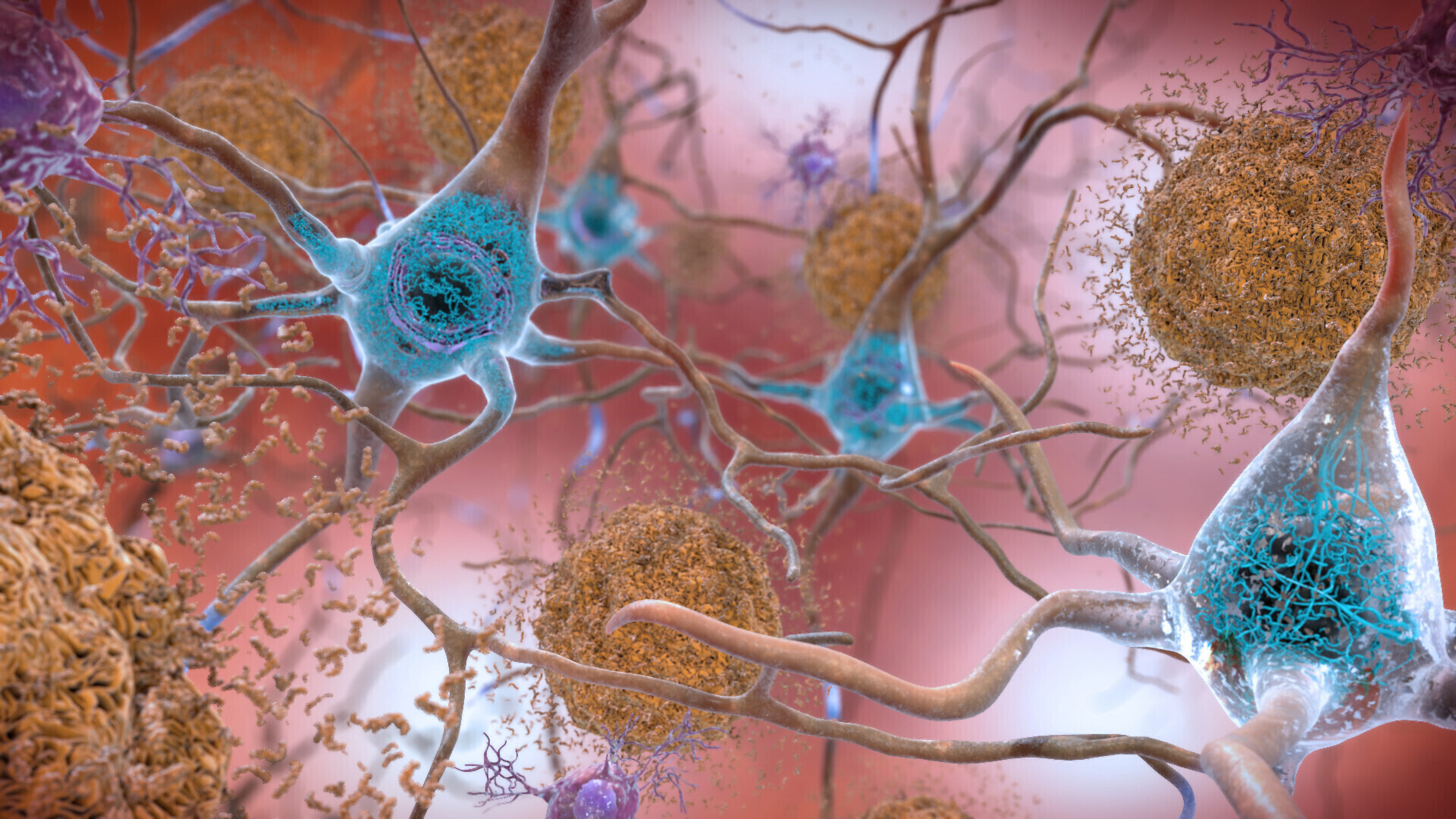

Researchers say we appear to be at the start of a new era for Alzheimer’s treatment. Trial results published in January showed that for the first time a drug has been able to slow the cognitive decline characteristic of the disease. The drug, lecanemab, is a monoclonal antibody that works by binding to a key protein linked to the malady, called amyloid-beta, and removing it from the body. Experts say the results offer hope that the slow, inexorable loss of memory and eventual death brought by Alzheimer’s may one day be a thing of the past.

The Gazette spoke with Scott McGinnis, an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Alzheimer’s disease expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, about the results and a new clinical trial testing whether the same drug given even earlier can prevent its progression.

Q&A

Scott McGinnis

GAZETTE: The results of the Clarity AD trial have some saying we’ve entered a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Do you agree?

McGINNIS: It’s appropriate to consider it a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Until we obtained the results of this study, trials suggested that the only mode of treatment was what we would call a “symptomatic therapeutic.” That might give a modest boost to cognitive performance — to memory and thinking and performance in usual daily activities. But a symptomatic drug does not act on the fundamental pathophysiology, the mechanisms, of the disease. The Clarity AD study was the first that unambiguously suggested a disease-modifying effect with clear clinical benefit. A couple of weeks ago, we also learned a study with a second drug, donanemab, yielded similar results.

GAZETTE: Hasn’t amyloid beta, which forms Alzheimer’s characteristic plaques in the brain and which was the target in this study, been a target in previous trials that have not been effective?

McGINNIS: That’s true. Amyloid beta removal has been the most widely studied mechanism in the field. Over the last 15 to 20 years, we’ve been trying to lower beta amyloid, and we’ve been uncertain about the benefits until this point. Unfavorable results in study after study contributed to a debate in the field about how important beta amyloid is in the disease process. To be fair, this debate is not completely settled, and the results of Clarity AD do not suggest that lecanemab is a cure for the disease. The results do, however, provide enough evidence to support the hypothesis that there is a disease-modifying effect via amyloid removal.

GAZETTE: Do we know how much of the decline in Alzheimer’s is due to beta amyloid?

McGINNIS: There are two proteins that define Alzheimer’s disease. The gold standard for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease is identifying amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles. We know that amyloid beta plaques form in the brain early, prior to accumulation of tau and prior to changes in memory and thinking. In fact, the levels and locations of tau accumulation correlate much better with symptoms than the levels and locations of amyloid. But amyloid might directly “fuel the fire” to accelerated changes in tau and other downstream mechanisms, a hypothesis supported by basic science research and the findings in Clarity AD that treatment with lecanemab lowered levels of not just amyloid beta but also levels of tau and neurodegeneration in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

GAZETTE: In the Clarity AD trial, what’s the magnitude of the effect they saw?

McGINNIS: The relevant standards in the trial — set by the FDA and others — were to see two clinical benefits for the drug to be considered effective. One was a benefit on tests of memory and thinking, a cognitive benefit. The other was a benefit in terms of the performance in usual daily activities, a functional benefit. Lecanemab met both of these standards by slowing the rate of decline by approximately 25 to 35 percent compared to placebo on measures of cognitive and functional decline over the 18-month studies.

“In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal.”

Steven M. Smith

GAZETTE: What are the key questions that remain?

McGINNIS: An important question relates to the stages at which the interventions were done. The study was done in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer dementia. People who have mild cognitive impairment have retained their independence in instrumental activities of daily living — for example, driving, taking medications, managing finances, errands, chores — but have cognitive and memory changes beyond what we would attribute to normal aging. When people transition to mild dementia, they’re a bit further along. The study was for people within that spectrum but there’s some reason to believe that intervening even earlier might be more effective, as is the case with many other medical conditions.

We’re doing a study here called the AHEAD study that is investigating the effects of lecanemab when administered earlier, in cognitively normal individuals who have elevated brain amyloid, to see whether we see a preventative benefit. The hope is that we would at least see a delay to onset of cognitive impairment and a favorable effect not only on amyloid biomarkers, but other biomarkers that might capture progression of the disease.

GAZETTE: Is anybody in that study treatment yet or are you still enrolling?

McGINNIS: There’s a rolling enrollment, so there are people who are in the double-blind phase of treatment, receiving either the drug or the placebo. But the enrollment target hasn’t been reached yet so we’re still accepting new participants.

GAZETTE: Is it likely that we may see drug cocktails that go after tau and amyloid? Is that a future approach?

McGINNIS: It has not yet been tried, but those of us in the field are very excited at the prospect of these studies. There’s been a lot of work in recent years on developing therapeutics that target tau, and I think we’re on the cusp of some important breakthroughs. This is key, considering evidence that spreading of tau from cell to cell might contribute to progression of the disease. Additionally, for some time, we’ve had a suspicion that we will likely have to target multiple different aspects of the disease process, as is the case with most types of cancer treatment. Many in our field believe that we will obtain the most success when we identify the most pertinent mechanisms for subgroups of people with Alzheimer’s disease and then specifically target those mechanisms. Examples might include metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, and problems with elements of cellular processing, including mitochondrial functioning and processing old or damaged proteins. Multi-drug trials represent a natural next step.

GAZETTE: What about side effects from this drug?

McGINNIS: We’ve known for a long time that drugs in this class, antibodies that harness the power of the immune system to remove amyloid, carry a risk of causing swelling in the brain. In most cases, it’s asymptomatic and just detected by MRI scan. In Clarity AD, while 12 to 13 percent of participants receiving lecanemab had some level of swelling detected by MRI, it was symptomatic in only about 3 percent of participants and mild in most of those cases.

Another potential side effect is bleeding in the brain or on the surface of the brain. When we see bleeding, it’s usually very small, pinpoint areas of bleeding in the brain that are also asymptomatic. A subset of people with Alzheimer’s disease who don’t receive any treatment are going to have these because they have amyloid in their blood vessels, and it’s important that we screen for this with an MRI scan before a person receives treatment. In Clarity AD, we saw a rate of 9 percent in the placebo group and about 17 percent in the treatment group, many of those cases in conjunction with swelling and mostly asymptomatic.

The scenario that everybody worries about is a hemorrhagic stroke, a larger area of bleeding. That was much less common in this study, less than 1 percent of people. Unlike similar studies, this study allowed subjects to be on anticoagulation medications, which thin the blood to prevent or treat clots. The rate of macro hemorrhage — larger bleeds — was between 2 and 3 percent in the anticoagulated participants. There were some highly publicized cases including a patient who had a stroke, presented for treatment, received a medication to dissolve clots, then had a pretty bad hemorrhage. If the drug gets full FDA approval, is covered by insurance, and becomes clinically available, most physicians are probably not going to give it to people who are on anticoagulation. These are questions that we’ll have to work out as we learn more about the drug from ongoing research.

GAZETTE: Has this study, and these recent developments in the field, had an effect on patients?

McGINNIS: It has had a considerable impact. There’s a lot of interest in the possibility of receiving this drug or a similar drug, but our patients and their family members understand that this is not a cure. They understand that we’re talking about slowing down a rate of decline. In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal. So there’s hope. There’s optimism. Our patients, particularly patients who are at earlier stages of the disease, have their lives to live and are really interested in living life fully. Anything that can help them do that for a longer period of time is welcome.