‘Moral breakdown is a fake problem’

And guess what? It’s not just your grandpa who needs a dose of reality.

Kids these days. Where did all the good guys go? We never used to lock the doors! For years, Adam M. Mastroianni bristled at pronouncements of declining human decency.

“One of my earliest Facebook statuses was: I get so annoyed when people make sweeping claims about history without actual knowledge of it,” said Mastroianni, who earned his Ph.D. in psychology at Harvard in 2021. “I was apparently very mad about people having this sense that today is somehow different from the past.”

In a paper published this month in Nature, Mastroianni, now a postdoctoral research scholar at Columbia Business School, channels that frustration into a rebuff. The experimental psychologist not only provides evidence that kindness, honesty, and civility are stable or have perhaps even increased in recent decades, he also marries two well-established concepts to explain why the illusion of moral decline persists.

First, Mastroianni needed to prove the prevalence of “good old days” nostalgia. He partnered with Daniel T. Gilbert, Harvard’s Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology, to scour databases for surveys that asked people worldwide about perceived morality past and present. Hundreds of relevant surveys were identified, dating as far back as 1949. For example, in 1987 Gallup asked: “Compared to 10 years ago, are people more honest, less honest, or about the same today?”

The researchers also conducted their own surveys online, with questions tailored more precisely to their inquiry. This approach yielded similar findings. “People say it just gets worse and worse — that moral decline has been happening their whole lives and it’s still happening today,” summarized Mastroianni, who also authors the “Experimental History” newsletter on Substack.

Interestingly, these perceptions varied little along demographic lines. “If you ask people about decline over their entire lives, older people do report more, but they’ve been alive longer,” Mastroianni said. “Older and younger people perceive the same rate of decline.”

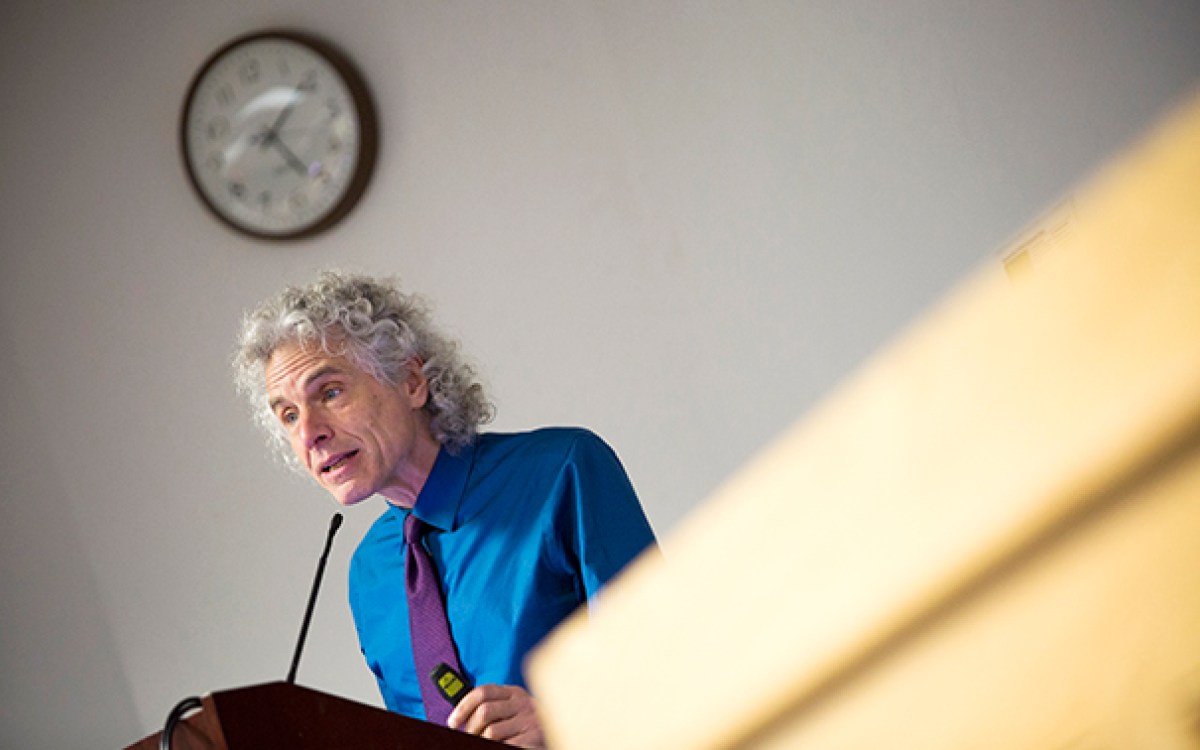

Adam Mastroianni takes on “good old days” nostalgia in his latest research.

Photo by Douglas Mastroianni

In the study’s second phase, the researchers asked whether everybody is right about everybody else. Is pro-social behavior really plummeting? An obvious retort comes from Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology Steven Pinker, whose work has shown steadily declining rates of war, genocide, child abuse, and other forms violence over the past 2,000 years. “However, that isn’t what we found people mean when they say morality is declining,” Mastroianni noted. “What they really mean is things like respect and kindness.”

Again, the researchers turned to surveys. They found more than 100, administered between 1965 and 2020, that asked people about moral behavior. One survey gauged current rates of volunteerism; another asked whether the respondent had helped a stranger over the past month. “We find that, on none of these items, is there a meaningful change over time,” Mastroianni said.

Also cited is a 2022 meta-analysis of 511 lab experiments, conducted between 1961 and 2017, that specifically measured levels of cooperation. The analysts fully expected to find cooperation falling over the past several decades. “They found the opposite!” Mastroianni said. “Cooperation rates went up by 10 percent.”

“Both biased attention and biased memory have been observed cross-culturally, so it also makes sense that you would find the perception of moral decline all over the world.”

Having found that moral decline is an illusion, the researchers closed their paper with an explanation based on two psychological tendencies. The first, known as biased exposure, relates to how negative information disproportionately captures human attention and is more likely to be broadcast to others. “Every day you look out on the world, and what you see is people being bad to one another,” Mastroianni said.

The other phenomenon, biased memory, pertains to the way recollections fade over time. “Say you got turned down for prom,” Mastroianni said. “That was probably a pretty terrible experience at the time, but looking back, maybe it’s funny. If you had a great prom, that memory is probably still pretty good. Both bad and good fade, but bad fades faster.”

If both phenomena play out at once, Mastroianni realized, a person could be left with the impression that things are changing for the worse. “We call this mechanism BEAM (Biased Exposure and Memory), and it fits with some of our more surprising results,” he wrote in a recent Substack post. “BEAM predicts that both older and younger people should perceive moral decline, and they do. It predicts that people should perceive more decline over longer intervals, and they do. Both biased attention and biased memory have been observed cross-culturally, so it also makes sense that you would find the perception of moral decline all over the world.”

As Mastroianni came to see it, the upshot is worse than mere annoyance. The research project, which was also his dissertation, underscores the political danger of romanticizing the past. Aspiring despots can and do prey upon declinist nostalgia, and the citizenry appears ready to squander precious resources on it. The new paper cites a 2015 Pew Research Center poll in which 76 percent of Americans agreed that “addressing the moral breakdown of the country” should be a high priority for government policy and spending.

“There are many real problems facing society today,” Mastroianni concluded. “Fortunately, moral breakdown is a fake problem, and we don’t need to spend any resources on it.”