Photos by Stephanie Mitchell, Kris Snibbe, and Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographers

5 faculty members named Harvard College Professors

Recognized for excellence in teaching in fields ranging from biophysics to cultural studies

Five faculty members have been awarded a Harvard College Professorship for excellence in undergraduate teaching, in fields ranging from biophysics to cultural studies. Claudine Gay, Edgerley Family Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, announced the recipients on May 2. They are:

• Fiery Cushman, professor of psychology

• Philip Deloria, Leverett Saltonstall Professor of History

• Sean Eddy, Ellmore C. Patterson Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology

• Zhiming Kuang, Gordon McKay Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Science

• Mara Prentiss, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics

“I am so pleased to recognize these five colleagues for their contributions to undergraduate teaching and their support and mentorship of students, as well as their work in graduate education and research,” Gay said. “Their dedication, passion, and innovation in teaching has had a profound impact on our students’ lives across a wide range of disciplines within the arts and sciences.”

Launched in 1997 with a gift from John and Frances Loeb, the Harvard College Professors are selected for their distinguished contributions to undergraduate teaching. Awardees will hold the title for five years and receive support of their choosing: a research fund, a summer salary, or a semester of paid leave.

Fiery Cushman.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Deciding where to eat and other spontaneous thoughts

Cushman, an experimental psychologist, often frames his courses by presenting an argument — such as an idea about what makes humans unique as a species — and his students learn the subject material while considering the larger question.

“The approach that I’ve taken with social psychology is to allow that information to be conveyed in service of a bigger and more uncertain argument where the students are my peers and deciding whether they buy it or not,” Cushman said.

Cushman’s area of expertise is decision-making, especially moral decision-making. Lately his research focus has been trying to understand which thoughts spontaneously come to people’s minds, and why. For example, when deciding where to eat lunch in a city with myriad options, a few may come to mind first. Cushman is interested in how that mental “menu” is created.

He notes a contrast between his research, where results are often prolonged and uncertain, and his teaching, in which he often sees immediate results. Putting effort into teaching — finding the best way to present the material, meeting with students for assistance and advice outside of class — is sure to deliver rewarding results, according to Cushman.

“By investing in those things, you get to see immediate impact and change in students’ performance,” Cushman said. “It gives me a nice balance to have a garden that I can work in where I know if I put time in, I’m going to get fruits out.”

Philip Deloria.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

American cultural studies meets Native American studies (and sometimes, hiking)

The way Deloria teaches about history has varied over the years, between content-based courses focused on meeting a list of learning objectives, to experiential hands-on learning that involves hiking mountains. At Harvard today, he said he’s found a good balance between the two.

“I’ve always liked thinking about how one does more than convey information,” Deloria said. “How one teaches skills, how one engages students at a personal level in ways that actually make meaning out of their learning experience.”

Deloria’s research work lies at the intersection of American cultural studies and Native American studies, focusing on the history of relations among American Indian peoples and the U.S., as well as the histories of Indigenous people globally. Lately, his inquiries have focused on how Native American people live within the expectations of non-Native Americans. He’s also working on a project about experiences of the 1833 Leonid meteor storm.

Deloria started his career as a middle school band and orchestra teacher. He says that experience gives him insight into the positive impact a good teacher can have on a student’s life.

“If we as teachers are recognizing that we actually have those opportunities to work with students and to shape and change their lives for the good and the positive, how exciting is that?”

Sean Eddy.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Decoding evolutionary history like a long-distance runner

Eddy frequently tells his students that learning is like long-distance running. While it seems like some people may be innately better at it, it’s mostly about long-term dedication. It’s a lesson Eddy pulls from his own past, adding that when he was an undergraduate, school did not come naturally to him.

“You get out what you put into it, you get better and better with the discipline and the effort,” Eddy said. “You can’t compare yourself to somebody else, because they’re somewhere else on that curve. They really respond to that.”

In his computational genomics research lab, Eddy works to decipher the evolutionary history of life — how molecular biology works, and how organisms on the planet evolved over time — by analyzing genome sequences. The lab develops algorithms and software to compare these sequences.

In teaching, Eddy believes in learning by doing, and organizes his course around biological data analysis problems, a new one each week, which require students to use code and critical thinking skills to solve.

“I don’t think you learn anything by listening to somebody else talk,” Eddy said. “You have to do it, and you have to be interested in it. The idea is that the problem has to be interesting and it has to be engaging so that it doesn’t feel like grunt work.”

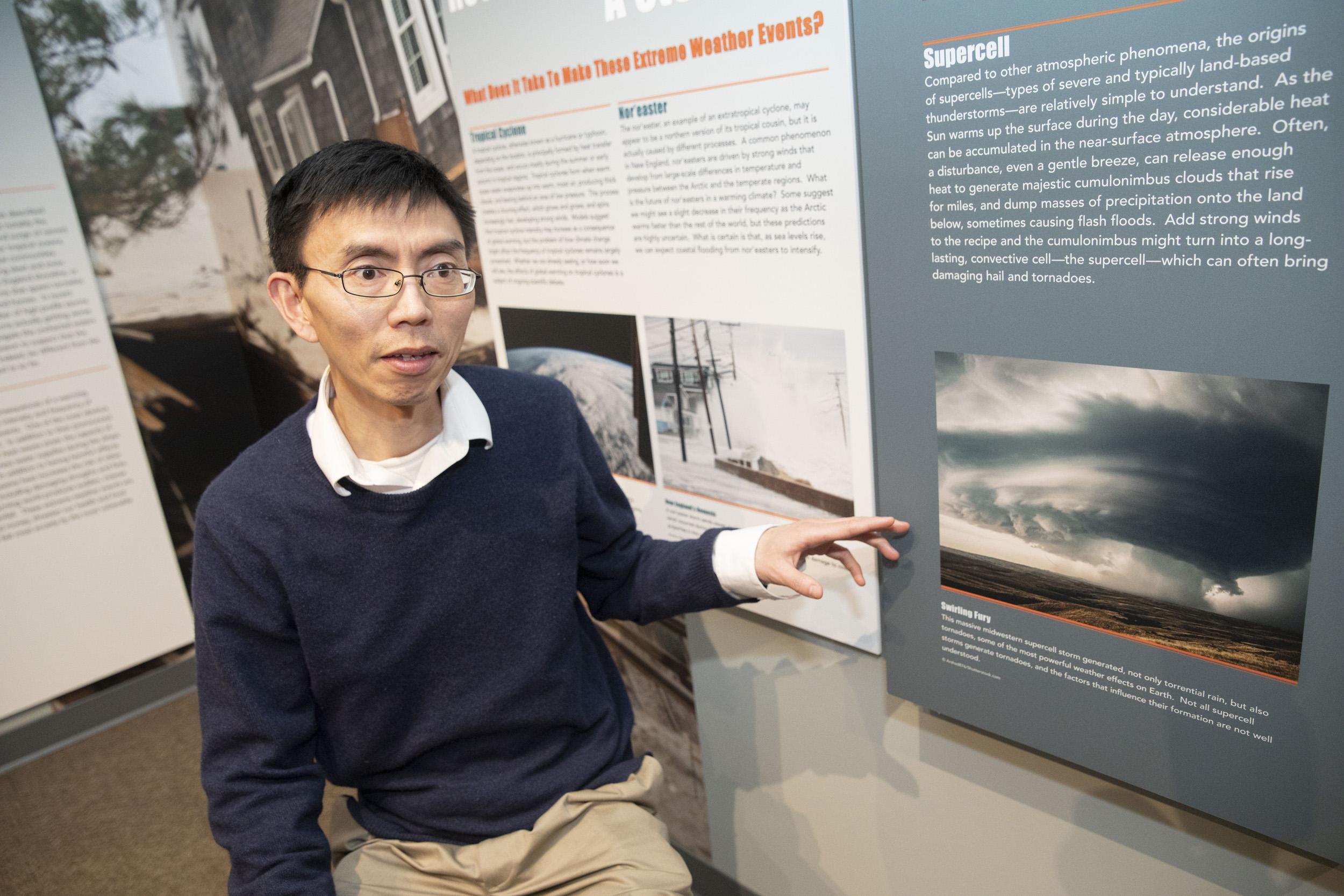

Zhiming Kuang.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Active learning about climate systems

Kuang, an atmospheric physicist, has been exploring a hybrid approach in his courses, combining traditional lectures and problem sets — which he says provide the “scaffolding” for the course — with active learning, which helps keep the students engaged. In Kuang’s courses, active learning might involve in-class exercises, mini group projects, and larger projects that are open-ended and ask students to apply concepts to areas of study they want to explore further.

“It is most rewarding to see the enthusiasm with which students apply what they learn in class to problems they are interested in,” Kuang said.

He dedicates most of his research to better understanding moist turbulence, which produces much of the clouds and rainfall, and shapes many of the aspects of the climate system. He researches the response of moist turbulence to “perturbations” such as the rising carbon dioxide concentration, and is currently working to find principled ways of using data-driven methods to improve climate theories and models.

“Teaching Harvard undergraduates has been a great privilege,” Kuang said. “Their amazing creativity and energy is what makes teaching fun, and I learn so much from them. I learn also from the many devoted teachers around me, who inspire me to continue to improve.”

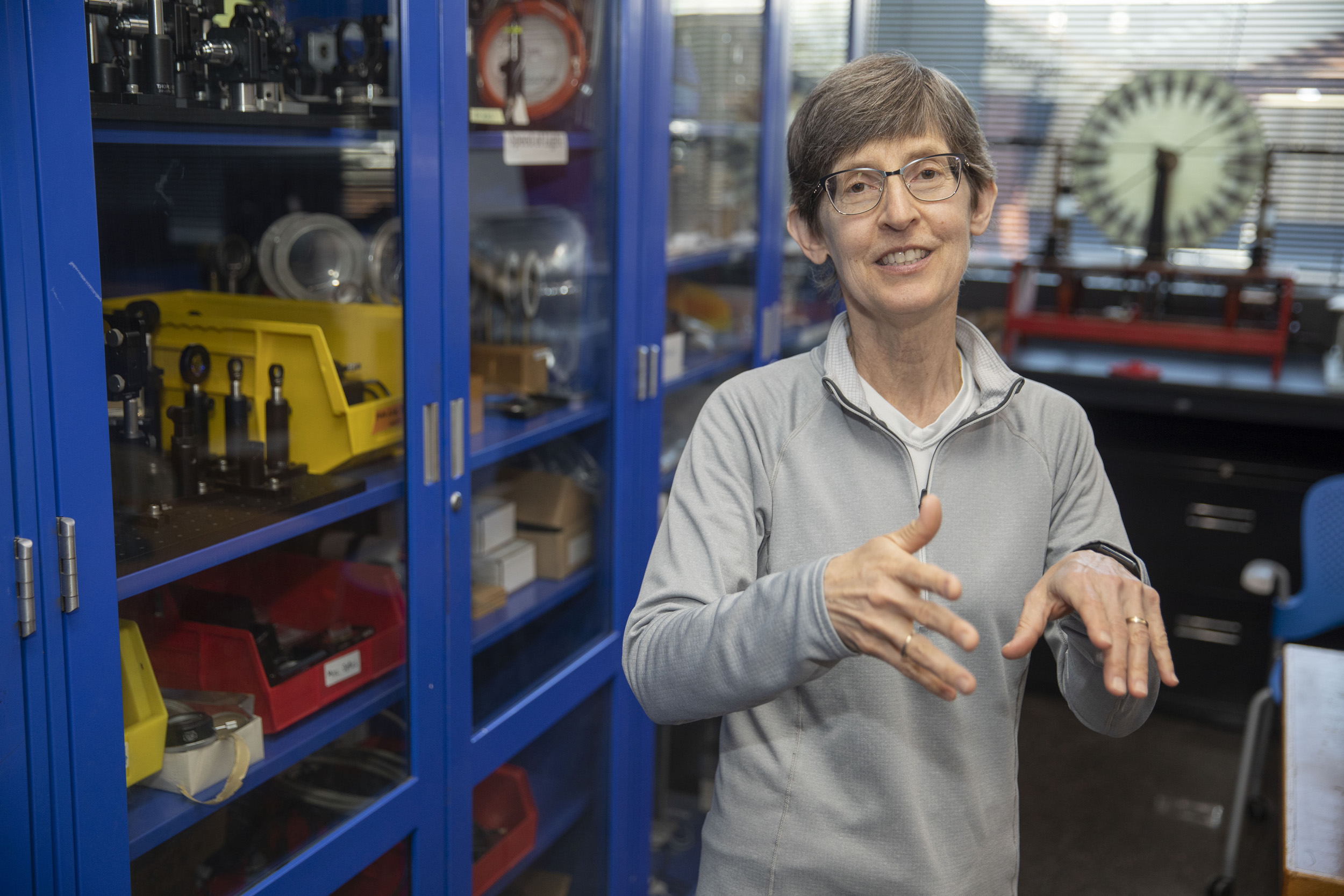

Mara Prentiss.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Solving problems, asking questions in the lab

Prentiss, who teaches atomic physics and biophysics, says lab classes offer the ideal atmosphere for teaching, allowing her to connect with students in small-group settings where she can get a sense for their different interests and perspectives. Although she teaches the same lab five days a week, Prentiss said each class ends up being very different because she adjusts the lessons for each group.

“It’s a chance to get to know them in a way that just isn’t possible in a classroom,” Prentiss said. “In lab, I can actually talk to each student and see where they are, which allows me to work with them as they develop their own individual vision of the material.”

In her research lab, Prentiss has tackled many of the world’s challenges, including developing a method for inexpensively making an optical tweezer for more accessible research, and showing that some self-assembling systems can overcome the trade-off between speed and stability. Much of the research currently ongoing in her lab focuses on RecA family proteins, which play a vital role in DNA recombination and repair, and she’s also been looking at a new approach to antibacterials.

Prentiss is glad when students ask questions that make her think differently about a scientific concept, saying those interactions help her keep learning.

“I think that teaching undergrads actually makes us better researchers,” Prentiss said. “It keeps researchers from going into tunnel vision, it keeps us looking at problems from new perspectives.”