Desire to battle climate change rooted in childhood

Environmental science, engineering doctoral student grew up next door to family’s palm-oil refinery outside Bangkok

When Ju Chulakadabba was in elementary school in Thailand, she learned that industrial emissions are one important way that humans are changing the global climate. That’s when she realized that trying to make a difference wouldn’t necessarily be a far-off concern in her case, but a family matter.

Chulakadabba, a Ph.D. student in environmental science and engineering at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, grew up next door to a palm-oil refinery on the outskirts of Bangkok. The factory, which employs more than 100 workers, was owned by her grandparents and remains a family business. Chulakadabba grew up surrounded by extended family — she’s the youngest of eight cousins — and remembers playing inside the factory in a large pile of clay used to transform the naturally reddish palm oil to the clear yellow liquid used in a dizzying array of prepared food, cosmetics, and consumer products throughout the world.

Chulakadabba never worked there — her mother became a psychiatrist instead of entering the family business — but she does plan to return and apply her education in environmental engineering to help make the facility more sustainable. In the meantime, she’s fostered her interest in the environment during undergraduate work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and most recently in the lab of Steven Wofsy, Harvard’s Abbott Lawrence Rotch Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Science.

“I feel like my family is a part of the issue,” Chulakadabba said. “I want to do something.”

That desire had her flying around the skies near Colorado last fall in a Gulfstream V jet mounted with methane-sensing instruments. The eight-hour flight acted as something of a proving ground for a project, called MethaneAIR, which will send the jet flying around the country later this year mapping sources of methane, a greenhouse gas much more potent than carbon dioxide. The flight also tested instruments and algorithms for a second, more ambitious project called MethaneSAT. MethaneSAT has a similar goal except, instead of a plane, the platform is a satellite — expected to launch in late 2023 or early 2024 — and the hunt for methane sources will be global rather than national.

“My family benefited from the factory. I have a good education because of it, so I want to return and do something good.”

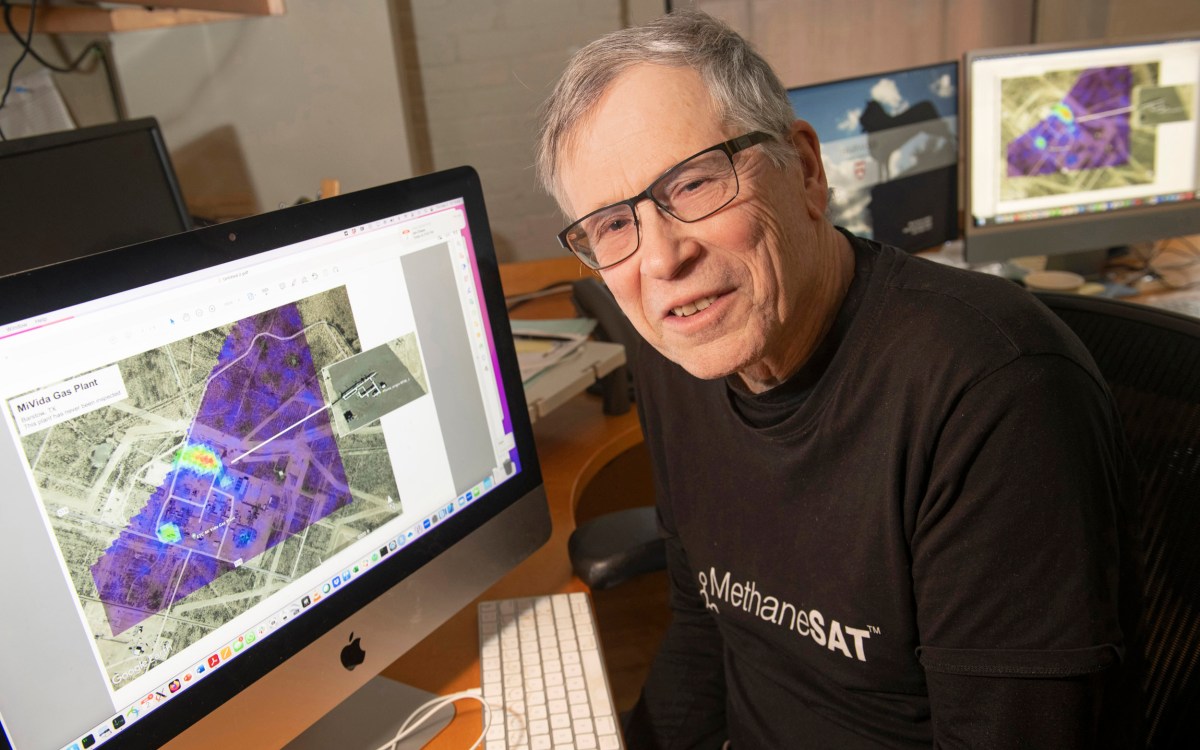

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The projects are being conducted in collaboration with the Environmental Defense Fund, which is hoping to use data they generate to reduce methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure by nearly half by 2025. Chulakadabba’s role is designing algorithms that quantify methane sources in the data.

Though carbon dioxide has received much of the attention as a climate-warming gas, methane makes a significant contribution — roughly 25 percent that of CO2 — to warming the planet, Wofsy said. Because it is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, far less methane is emitted to get that effect, which is why Wofsy terms it something of a “low-hanging fruit” in climate remediation.

Chulakadabba has been looking for ways to help the environment for many years. In middle school, she created a project that used the industrial clay she once played with — called “bleaching earth” in the industry — to remove copper from wastewater.

“I felt like this issue directly affected me, and it was fascinating to me that I could do something about it,” Chulakadabba said of the project. “It was small-scale but had the possibility that I could convert it into something bigger.”

Environmentalists say processing palm oil creates pollutants that taint the air and water, but perhaps the biggest environmental threat posed by the industry involves the large-scale deforestation and habitat disruption that takes place to clear areas for growing, primarily in portions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Chulakadabba moved to the U.S. and finished high school in New Jersey. While at MIT for her undergraduate studies, she did research on indoor air pollution, detecting methane emissions in a lake, doing models to examine climate impacts in China, and using satellite data to measure plant response to water availability.

“I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, though I knew I wanted to do something with the environment,” Chulakadabba said. “Eventually, I want to go back to the factory and make it greener, or at least make the quality of life of people in that area better. My family benefited from the factory. I have a good education because of it, so I want to return and do something good.”

Chulakadabba said her years at MIT convinced her that she was most interested in projects with broad effects.

“I enjoyed doing something that has a bigger impact,” Chulakadabba said. “I feel like the most important issue today is climate change, and if I can do something with that, I can help a larger group of people.”

As her MIT graduation neared, Chulakadabba looked at several environmental engineering graduate programs. She wanted one that blended computation and experimentation, but found that most programs focused more heavily on one or the other. Her adviser suggested she talk to Wofsy, and the more she learned about MethaneSAT, the more she thought it would be a good fit.

She had to talk her way onto the project, however, because Wofsy told her that it wasn’t ideal for a Ph.D. Rather than focusing on creating new knowledge, its ultimate goal was to affect policy around methane emissions. That might reduce the number of scientific papers that result, Wofsy warned. But Chulakadabba stuck to her guns, and Wofsy let her join the effort.

Wofsy said Chulakadabba is among a modern cohort of graduate students who embrace the idea — even insist on it — that their work go beyond the science to have practical impact. While graduate students — three others work on MethaneSat with Chulakadabba — have always wanted their work to be impactful, he said it seems more important today, perhaps stemming from frustration over government inaction on climate change, which is getting worse by the day and carries a real existential threat.

“It turns out that in this generation of students are a sizable number strongly motivated to make the world a better place,” Wofsy said. “They embrace the idea that a Ph.D. in this area might be a little different than the normal Ph.D. Maybe they won’t get as many papers. That’s fine with them as long as they’re compensated by seeing impact.”