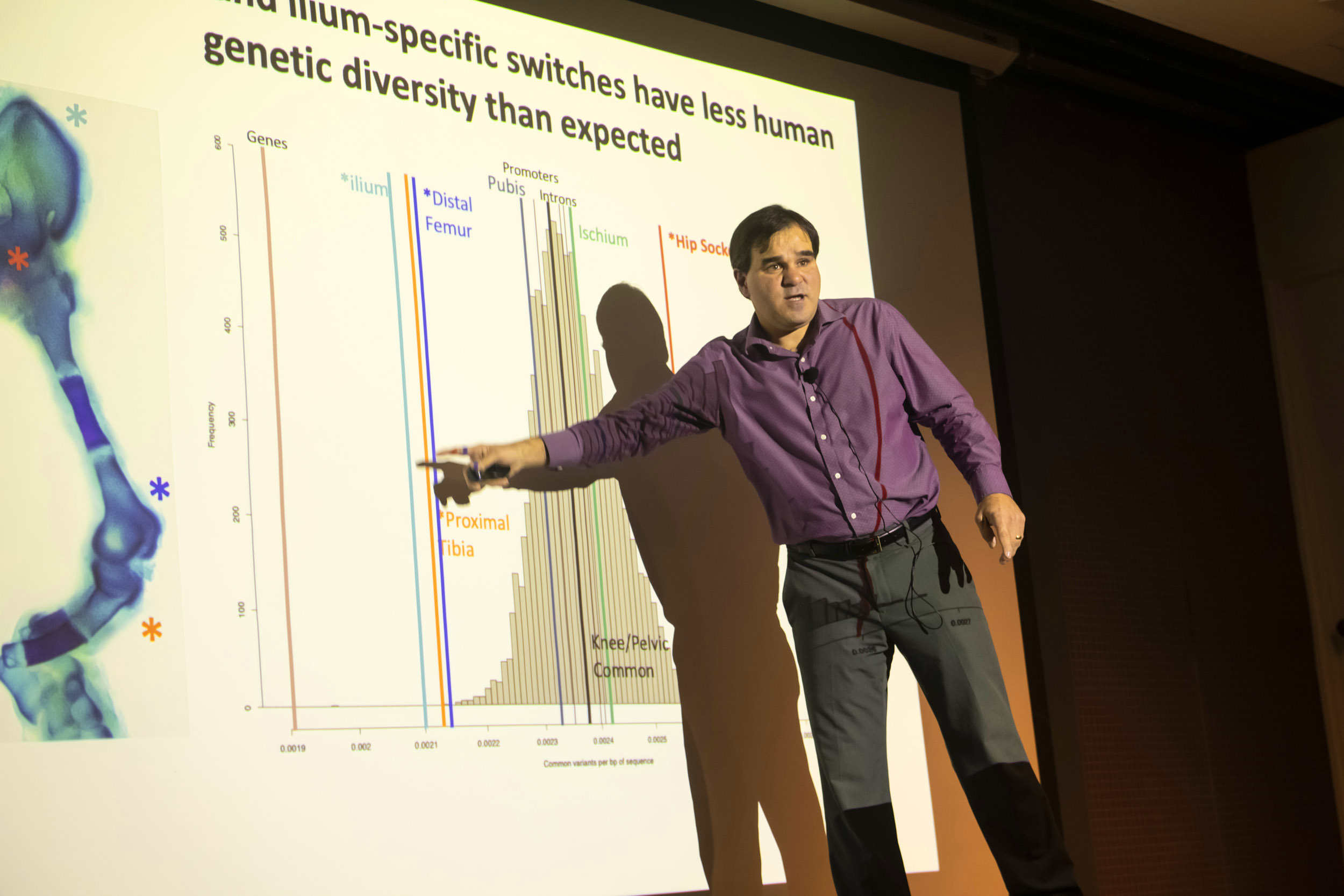

By 2040, nearly 40 percent of adults over 65 will have degenerative osteoarthritis, said human evolutionary biologist Terence D. Capellini in a recent lecture.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Evolution hurts sometimes

The same skeletal changes that allowed humans to walk upright make us vulnerable to knee osteoarthritis as we age

Over millions of years, humans have developed unique features — think of the opposable thumbs and complex brains that make it possible to read this article on a smartphone. But we’ve also developed unique diseases.

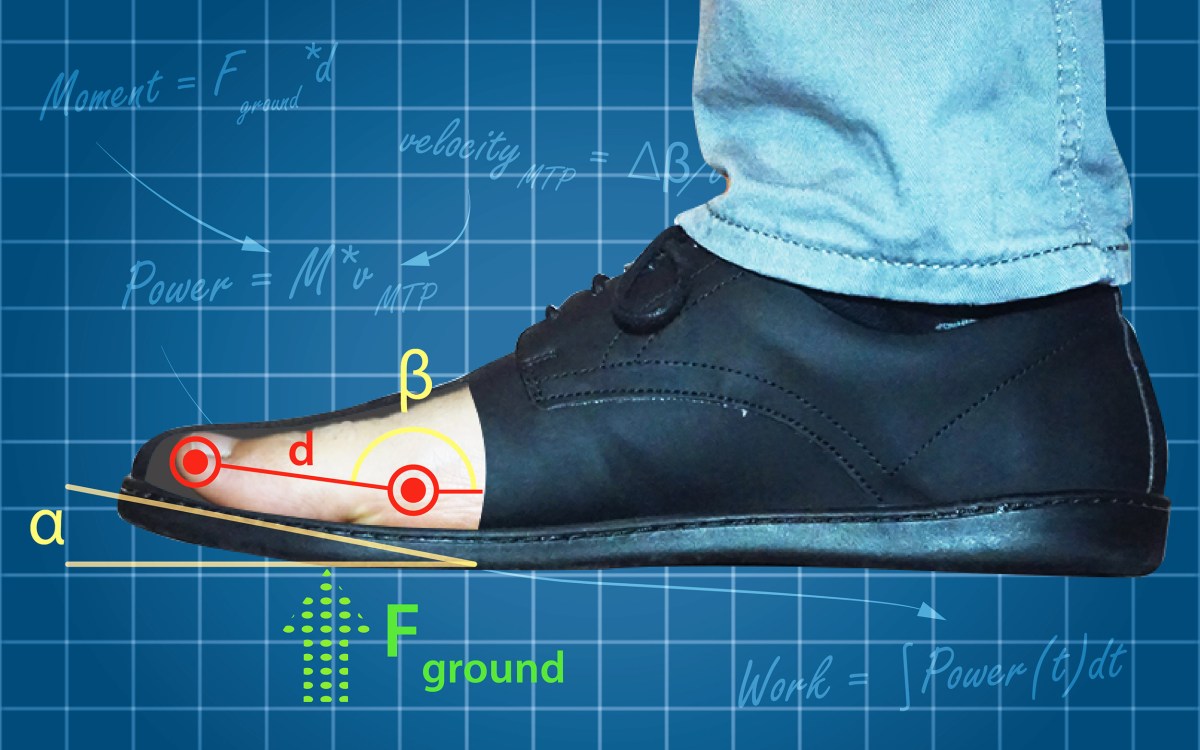

“When Evolution Hurts,” a recent talk hosted by the Museums of Science & Culture, explored the genetic research that is helping scientists better understand relationships between evolution and modern disease risk. In the lecture, human evolutionary biology Professor Terence D. Capellini focused on the link between bipedalism and knee osteoarthritis, a degenerative disease that afflicts 250 million people worldwide.

As humans developed to walk upright, said Capellini, the structure of our knee joints and pelvis changed. In our knees, we have a larger area of contact between the upper and lower leg bones. Thigh bones have become more angled and lower bones thicker to support weight. Our pelvises, compared to those of apes, got shorter, wider, with more curved blades to support a range of upright motion.

“Post cranial, this is the most changed skeletal structure in the body,” Capellini said. “It’s allowing us to walk on two legs and give birth to a large fetal head — both essential for human existence.”

Through time subtle alterations, occurring in utero, slightly changed those basic structures in some people. These alterations — say, a slightly more angled femur or rounded tibia — can cause severe wear and tear as we age.

“Having osteoarthritis of the knee is debilitating, and it has a lot of comorbidities associated with it, like heart disease and diabetes.”

By 2040, Capellini said, nearly 40 percent of adults over the age of 65 will have some form of degenerative osteoarthritis.

“Having osteoarthritis of the knee is debilitating, and it has a lot of comorbidities associated with it, like heart disease and diabetes,” he said.

So how do we prevent it? First, Capellini said, we need to identify the characteristics of the population who are not prone to the disease. His lab, using technology to study the human skeleton during development, has been able to determine what cells control the development of certain characteristics. Capellini described genetic “switches” — regulatory proteins that activate a genetic variation, or don’t. These switches, of which there are hundreds or thousands in each part of the skeleton, control the size, shape, and, ultimately, the longevity of your joints.

Next, using this research, Capellini and his team hope they can pinpoint these mutations for future therapies.

“What we can do is figure out how to therapeutically treat how switches act in the knee, and how they form to maintain a healthy knee,” he said.

For example, he said, if scientists are able to identify high-risk patients at an early age, they may be able to inform them about activities in which they should be careful engaging. Capellini notes that injury, in addition to genetic predisposition, increases the likelihood of developing osteoarthritis.

“It’s hard to say not to do activities,” he said. “But to be careful doing certain activities.”

Capellini’s presentation builds on his work in the Developmental and Evolutionary Genetics Lab and hypotheses published in his 2020 paper “Evolutionary Selection and Constraint on Human Knee Chondrocyte Regulation Impacts Osteoarthritis Risk.” The talk is part of an ongoing series by the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture. More information on upcoming events can be found on their website.