Finally, taking a bow

Many jazz greats knew names, music of these four women, but Radcliffe Fellow Maxine Gordon wants to make sure rest of us do too

Maxine Sullivan, one of four jazz musicians featured in Maxine Gordon’s upcoming book, performs in 1947 at the Village Vanguard in New York City.

Photo by William P. Gottlieb

Their names and music are not widely known today, but author Maxine Gordon, the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute, aims to rectify that injustice.

Gordon, a lifelong jazz fan and wife of Dexter Gordon, the late tenor saxophone great, spent decades working in the music business, mostly as a road and tour manager for jazz musicians. In 2018, she completed a book her husband had begun about his life, “Sophisticated Giant: The Life and Legacy of Dexter Gordon.”

During a talk Wednesday, Gordon previewed a project she’s researching during her fellowship about the lives of four Black women musicians who found success and built lasting careers despite facing “unrelenting obstacles” in the ultra-competitive, male-dominated music world between the 1930s and early 1970s: vocalists Maxine Sullivan and Velma Middleton, organist Shirley Scott, and Melba Liston, a trombonist and accomplished composer and arranger who worked with Dizzy Gillespie and Quincy Jones in the 1950s, and later, reggae star Bob Marley.

Gordon, who was friendly with Scott, said her goal is to bring the personal stories of these artists forward and explore the times in which they lived and worked. The work-in-progress will be titled “Quartette” and published by the new Howard University/Columbia University Press.

The glamorous Sullivan followed the path most readily open to women in jazz in the 1930s, touring as a singer with different big bands and small jazz groups, as well as performing in films and on Broadway. Her first big hit, improbably enough, was the Scottish folk song “Loch Lomond” in 1937. She’s one of only three women — the others are pianists Marian McPartland and Mary Lou Williams — captured in “A Great Day in Harlem,” Art Kane’s iconic 1958 Esquire photograph of more than 50 jazz luminaries gathered on the street between Fifth and Madison avenues.

Middleton, a burly singer who did breakdance-style routines in evening gowns and played poker offstage between numbers, performed with Louis Armstrong and his orchestra for nearly 20 years, doing close to 300 shows a year from the early 1940s until her death in 1961 at age 43 from a stroke.

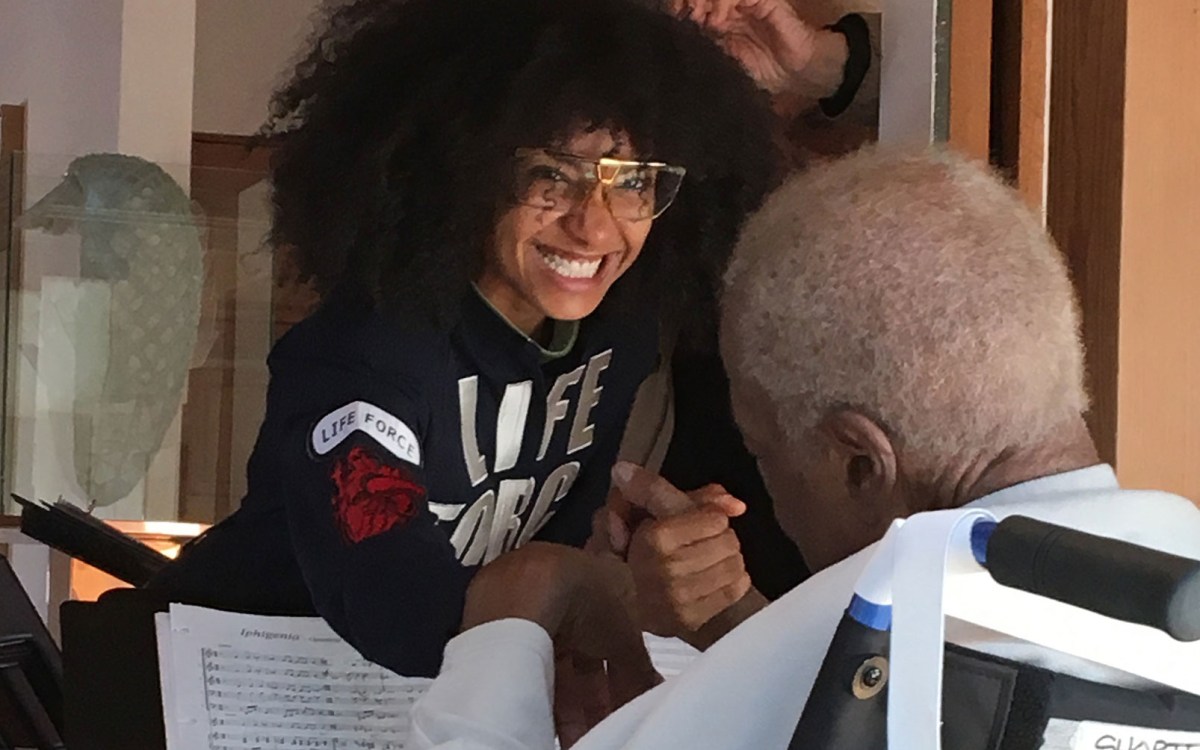

Maxine Gordon.

Photo courtesy of Harvard Radcliffe Institute

Liston, a childhood friend of Dexter Gordon, was an accomplished horn player when few, if any, women could be found in professional brass sections, especially on the trombone.

A trailblazer, she played, composed, and arranged for many jazz greats beyond Gillespie and Jones, including Williams and another pianist, Randy Weston. “Her stature as a trombone player, arranger, and composer is well-known in jazz circles, but there’s so much to learn from her life,” said Gordon.

Known as the “Queen of the Organ,” Scott played the Hammond B-3, a staple of jazz, blues, reggae, and rock from the late 1950s to the early ’70s. The Philadelphia native was still a teenager when she played her earliest gigs with John Coltrane before joining tenor saxophonist Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis’s band in 1955. She recorded 40 albums as a bandleader, a relative rarity in jazz, starting with “Great Scott!” in 1958 for the Impulse! label with legendary engineer Rudy Van Gelder behind the recording console.

Much of the racial and gender discrimination that Liston, Middleton, Scott, and Sullivan faced decades ago in the music industry is still with us. “It’s a serious problem,” said Gordon. While women are free today to play any instrument, teach at prestigious places like Berklee College of Music, and of course, work as professional musicians, they still do not get equal access to the most coveted gigs and venues for the same old reasons, she said.

“It has to do with money and capitalism and who controls it and who owns the record companies and the clubs — and they’re all white men.”

Gordon said researching the lives of these women has already “changed my life.” She pointed to the example of Middleton.

“She’s born in a place where Black people can get killed for being out after dark,” Gordon said of the vocalist’s “sundown” hometown of Holdenville, Oklahoma. Touring with Armstrong, Middleton traveled around the world for years to places where they were welcomed like visiting heads of state. “She’s in the U.S., but she got dressed in the back of a bus. They didn’t have dressing rooms where they played! So, it’s changed me.”