No stranger to improvisation

Bass player, composer, vocalist Devon Gates merges anthropology, music in Harvard-Berklee program

Devon Gates began to pluck the strings of her bass outside of Winthrop House on a recent afternoon. Notes of her solo filled the air as Gates quickly found her rhythm. Students passing took note; some, by the looks on their faces, appeared to connect. One man stopped to listen.

“She’s so musical,” Vijay Iyer, Franklin D. and Florence Rosenblatt Professor of the Arts, said. “We use that word sparingly with other musicians. It’s the highest compliment. It’s one thing to go through the motions and do everything ‘right.’ [It’s] another thing to really bring expressive artistry to the occasion. To make it matter to the listener. And she’s able to do that with everything she does.”

The desire to try new things and to engage with individuals — and communities — has been a major focus of what Gates ’23 has sought to do since arriving at Harvard as part of a dual degree program with Berklee College of Music. Gates, a social anthropology concentrator with a secondary in music, admitted she didn’t know what anthropology was before coming to Cambridge. But the Atlanta native has since found the perfect way to merge social anthropology and music into her everyday life. Gates refers to herself as a “native anthropologist” who studies the jazz community.

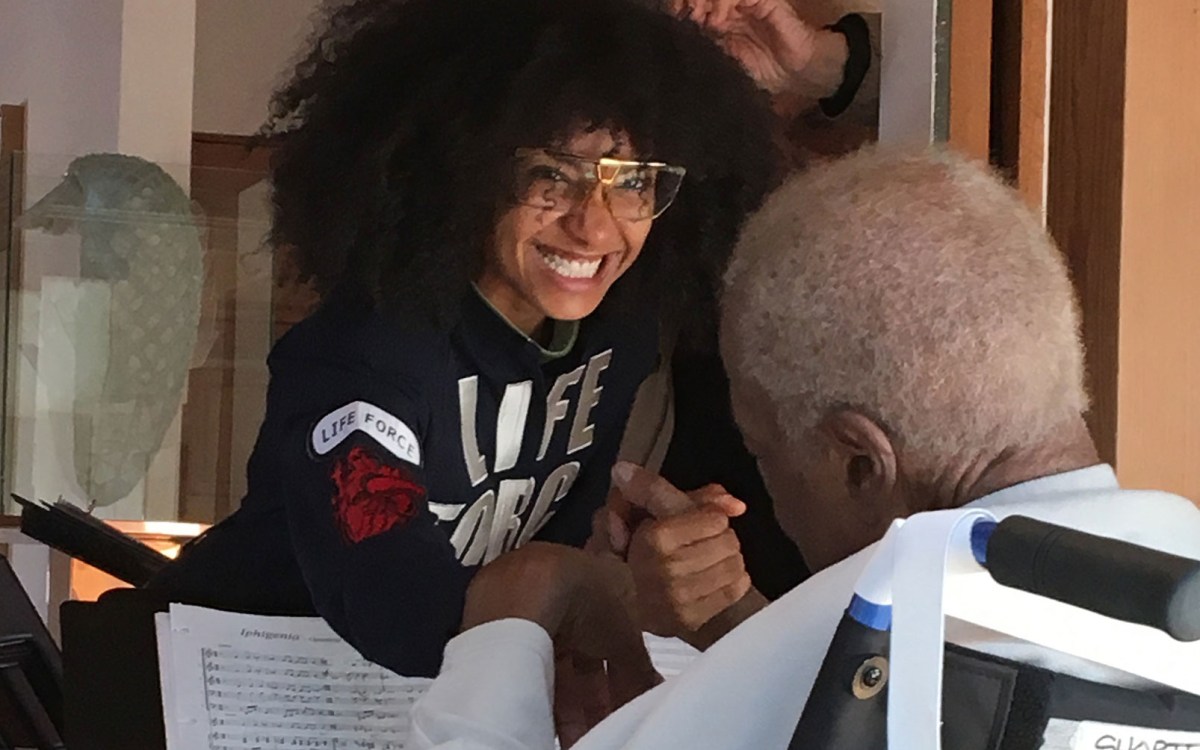

Gates plays on the Weeks Footbridge.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Iyer, an award-winning composer and pianist and former MacArthur Fellow, first taught Gates in the spring of 2020 in a workshop class that challenged students to create music in ad hoc ensembles, developing personal and musical relationships simultaneously in real time.

Gates fit in seamlessly with each group she joined, bringing dynamism and profound humility and support as an artist, player, and singer, her professor said.

She “was willing to take risks, which is what that format demands,” he said. “She was fearless, and I think that was the most exciting thing, that she wasn’t afraid to get up there, try something. If it didn’t work, she would try something different.”

For the past two years, Gates has worked with Berklee’s Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice. “Working with the institute on special projects that constructively help better conditions in our community and being able to mix all these worlds and really interact with people and issues that I care about is what drew me to anthropology,” she said. “I already had music.”

At the institute, Gates has worked on a broad range of projects, including helping put together a book of compositions called “New Standards: 101 Lead Sheets by Women Composers,” by author Terri Lyne Carrington, a Grammy-winning jazz drummer, composer, and educator. Gates worked diligently to reach out to composers, collect audio recordings, and brainstorm whom to include in the book. Her own work, “Don’t Wait,” is included. The collection of lead sheets aims to highlight the important work of often-underacknowledged female voices of jazz.

“It feels really surreal.” she said. “I love, respect, and admire so deeply all the women in the book. To have seen the book recently and see my name next to all of these incredible people is crazy, but also really inspiring.”

When she’s not with the Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice or performing at gigs around the country, Gates works with the Radcliffe Institute’s Law, Education and Justice Initiative alongside Professor Kaia Stern and the Prison Studies Project. Stern leads the Music and Justice working group that brings musical instruments and a group of Harvard students every week to adult incarcerated students from the I-Can Academy at Nashua Street Jail in Boston.

“It’s been really cool to go in every week and see how much joy [you] can bring [by giving] someone a violin for the first time and [showing] them how to play for a couple minutes,” she said. “The impact that has physically on someone is really special.”

Gates said it is critical to connect her music to different types of justice initiatives, inherent to the type of music she plays. “Black American music like jazz, gospel, and R&B are freedom music to me,” she said. “To play this music and to embody this music, it almost gives you a responsibility to use it for these sorts of things.”

As Gates continued to play her bass outside Winthrop House, Iyer said of his mentee, “It’s been astonishing to see how much she’s evolved in the time since” their first class together.

He recalled the time Gates seamlessly played alongside him in a spot usually inhabited by her Berklee Professor Linda May Han Oh. Gates not only played the complicated standard alongside Iyer but also introduced singing to the performance.

“That experience playing with her, getting the music together, for a trio performance, felt like being with colleagues,” he said. “As far as I’m concerned, she’s already one of us, and I can’t say that about everybody.”