“I was compelled to think about projected images because we’re surrounded by them in contemporary art as well as in life,” said Giuliana Bruno, discussing her new book.

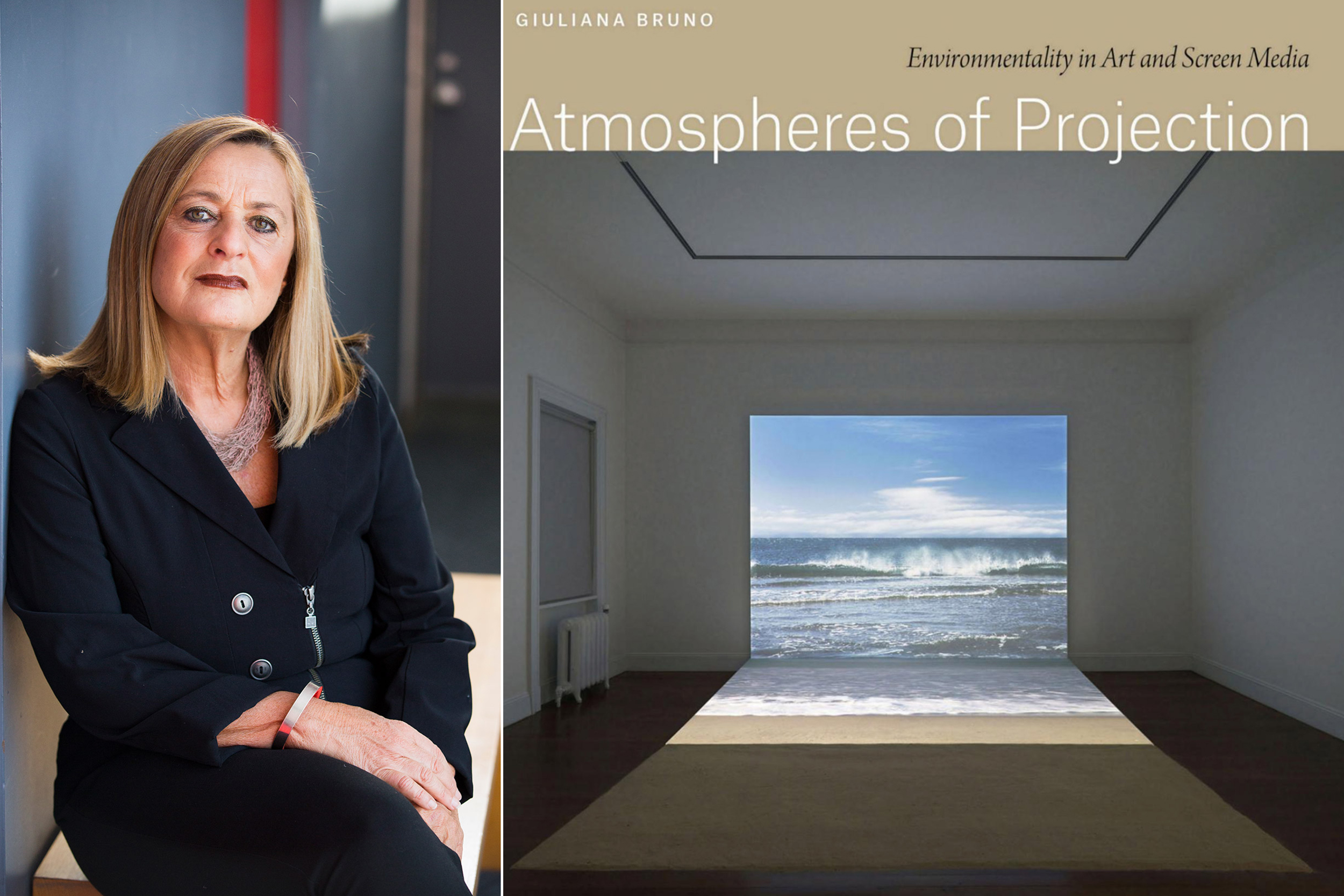

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Seeing ourselves in different light

Giuliana Bruno’s new book reclaims concepts of ‘projection’ as positive force connecting us to one another, affirming possibility of change

These days, we are surrounded by screens. But even before phones and tablets became our constant companions, projections and moving images captured our imagination. What these images mean and how we view them has long interested Giuliana Bruno, the Emmet Blakeney Gleason Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies.

In her new book “Atmospheres of Projection: Environmentality in Art and Screen Media,” she considers the interrelations of projection, atmosphere, and environment, reclaiming the concept of “projection” as a positive creative force.

“I was compelled to think about projected images because we’re surrounded by them in contemporary art as well as in life. We have screens everywhere, in museums and our homes,” said Bruno. “And thinking back in history, we’ve long been fascinated by shadows projected by a source of light onto a wall surface.” She harkens back to cave paintings — “images on walls that had to be seen by the light of torches” — noting: “Projection, born in prehistory, connects the history of humanity and the history of creativity.”

In recent times, however, the idea of “projection” has taken on negative connotations, largely because the term in psychoanalysis means the ability to displace one’s feelings onto another. “This has come to mean that anything unpleasant or negative in ourselves can be transferred onto another person or onto a space,” she said.

A negative association also dates back to Plato, whose allegory of the cave makes projection into deception. “The prisoners in the cave saw images of people ‘projected’ on the wall and believed these shadows to be real people,” Bruno stressed. “Thus images are seen to project illusions.” Since Plato’s cave became a metaphor for cinema, the spectator becomes a person locked in a space, looking passively at false, illusionary images projected on screens.

For Bruno, this reading misses the point. “Actually, the term projection originally comes from alchemy,” she explained in describing the potential of the projective process, through which substances can become transformed in a desired and positive way. In its original 15th-century sense, projection was used “to indicate transformation. In alchemy, it referred to the possibility of matters changing into one another, positively affirming metamorphosis as a form of creation.”

Using this definition, she coined the term “projective imagination” to describe a way of being open to change and to new interpretations. Projection enables us to view ourselves as positively connected to other beings and to the outside world, and to sense this contact as a potential energy of transformation.

“It’s affirming the positivity of being receptive to one another and relating to our environment. It is to understand that one benefits from these kinds of transfers between people, spaces, and things,” said Bruno. Looking at the transformations that happen through sympathy and empathy, or how our emotional atmospheres change when we let others in, she saw the urgency of rediscovering this ancient word’s original meaning.

“I work in aesthetics, and have a philosophical mind,” she said. “But I also am interested in history. And when you excavate into history or etymology, you realize that this transformative aspect was there but got defaced. Etymologically, projection is an act of ‘throwing forth.’ But that became to throw off, to cast off,” she said, noting the negative connotations of that phrase. “Instead of casting off, you could say projecting is a way of throwing forward — of moving forward.” In other words, it is a process that projects possibility.

These subtle linguistic differences matter, said Bruno. Intent on “reimagining these concepts, I look back at history not just to see how this concept of projection became transformed over time, but how it can transform our future,” she added. “I’d like to change these notions to re-establish a politics and aesthetics of interrelationality that can affect the way we live by affirming the possibility and potentiality of change.”

The arts, she noted, are key: “Some of the most important symptoms and potentials of cultural and social change emerge in the arts today.” For this reason, the second half of the book focuses on contemporary artists such as filmmaker Chantal Akerman and installation artist Robert Irwin. “I interpret and expose how the artistic imagination is effectively producing a new creative atmosphere, a new cultural atmosphere, and a new aesthetics.” In other words, new projections.