Steven Pinker criticized the movie’s depiction of people as greedy idiots in complete denial of reality, saying it ignores the difficulty faced in finding workable solutions.

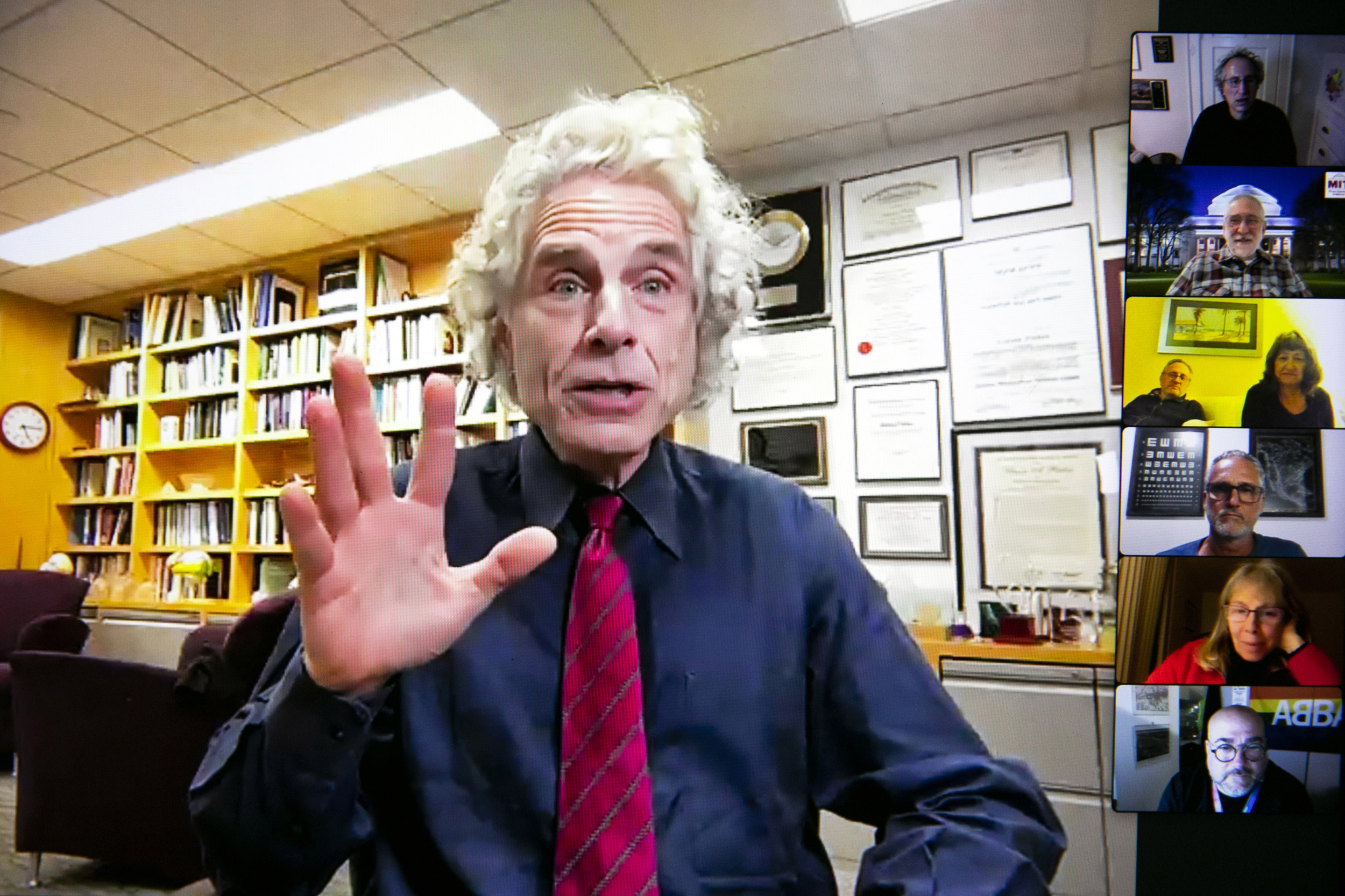

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Hollywood’s messaging problem: Sometimes people feel insulted

So you liked ‘Don’t Look Up’? Steven Pinker disagrees. Strongly.

Can laughter help lead us out of the climate crisis? Maybe. But if we’re laughing at one another, maybe not.

Experts in psychology, communications, and media studies clashed Tuesday on the utility of satire in conveying the urgency of climate action. If people are laughing, they noted, you know you have their attention. But as Steven Pinker pointed out, comedy is counterproductive when it belittles or embarrasses its target, particularly if that target is essential to finding a solution.

“This should not be thought of as a battle of good versus evil, with us, elites in Cambridge and Hollywood, looking down on all the morons who simply don’t acknowledge there’s a problem in the first place,” said Pinker, the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology. “It’s an extraordinarily difficult problem even for the most scientifically informed of our leaders.”

Pinker and colleagues Matthew Baum, Marvin Kalb Professor of Global Communications and professor of public policy at the Kennedy School, and Lauren Feldman, an associate professor of journalism and media studies at Rutgers University, discussed satire, misinformation, and climate change through the lens of the 2021 film “Don’t Look Up” in a conversation moderated by Sheila Jasanoff, Pforzheimer Professor of Science and Technology Studies at the Kennedy School and a professor of environmental science and public policy. The event was sponsored by Harvard’s Mind Brain Behavior Initiative.

“I really liked the movie. I thought it was effective in allowing people to recognize the failures of our institutions.”

Lauren Feldman, Rutgers University

The movie presents the story of scientists who discover a planet-killing comet heading toward Earth and struggle to convince politicians, the media, industry, and the public to act. Produced by Netflix, “Don’t Look Up” skewers a range of venal and superficial characters whose collective failures lead to global disaster.

Feldman, who published “A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar: The Serious Role of Comedy in Social Justice” in 2020, was a fan of “Don’t Look Up” on more than one level. Comedy can reach people in ways other forms of media cannot, she noted. She also welcomed Netflix’s decision to create a social action page to go along with the film.

“I really liked the movie,” she said. “I thought it was effective in allowing people to recognize the failures of our institutions. I thought it hopeful because I thought ‘that’s a metaphor’ and the compressed timeframe in which the characters had to address this comet allowed us to see the time that we’re wasting and realize that we could do something — no simple fix, no complete or perfect fix, but we do have solutions available to us.”

Pinker, on the other hand, found little to like in “Don’t Look Up,” either as entertainment or as a communications tool. The analogy between climate change, a problem of dizzying complexity, and a comet strike is simplistic enough that it might be considered its own form of climate disinformation, he said. Further, he criticized the movie’s depiction of people as greedy idiots in complete denial of reality, saying it ignores the difficulty faced in finding workable solutions even by those who take the problem seriously.

“I thought it was awful,” he said. “I thought the movie was puerile. I thought it was arrogant. I thought it was witless.”

Baum, too, thought the climate angle was strained, but pivoted to a real-life crisis that in his view the movie reflected all too well: the U.S. government response to the pandemic, when leaders, including the president, cast doubt on scientific facts, undercut epidemiologists, infectious disease physicians, and other experts, and echoed misinformation about which drugs and treatments might be effective.

“We saw our government institutions behave not that dissimilarly to what was being parodied on screen about a year prior,” Baum said. “Yes, it’s very cynical, but I’m not sure how far removed it is from what we lived through.”

Ultimately, the panelists said that viewers most receptive to the film’s climate message agreed with it in the first place. “Don’t Look Up” probably didn’t change a lot of minds among climate change deniers or those who don’t think the problem urgent enough to warrant the economic disruption some steps would require.

“There is no magic bullet for these complicated issues and there is no one thing the entertainment industry or anybody else is going to do to fix these problems,” Baum said, “but there’s no question, I think, that entertainment is one way of communicating messages.”