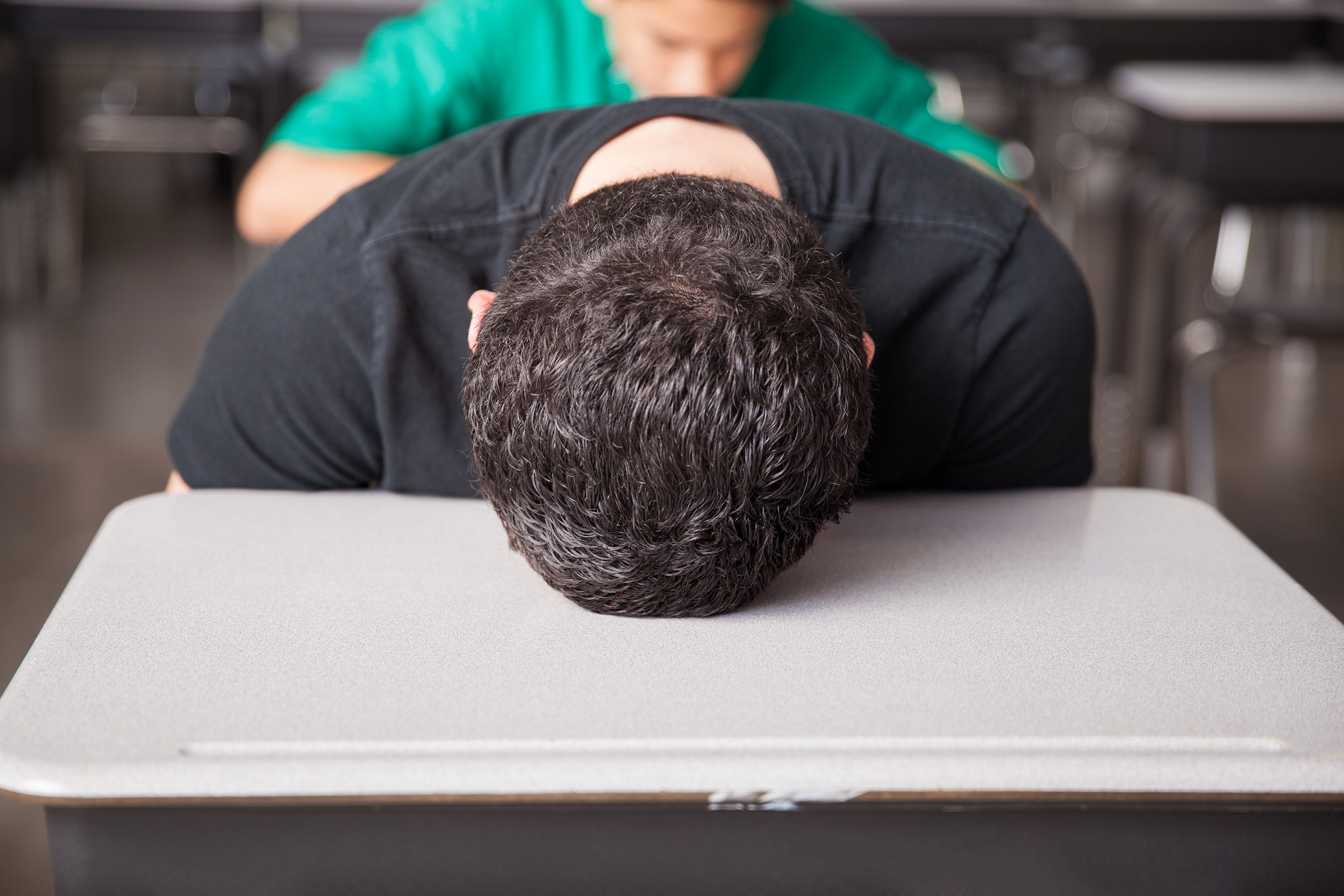

Parents are so wrong about teenage sleep and health

Study upends common myths around melatonin, weekends, school start times

As a new school year begins, Harvard-affiliated sleep health researchers have a message for parents and caregivers on teenage sleep: you’re wrong.

A study by investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital enlisted experts in adolescent sleep to identify myths. Researchers then surveyed parents and caregivers, finding that more than two-thirds believed in the top three most salient myths about sleep. These involved school start times, the safety of melatonin, and the effects of altered sleep patterns on the weekends. In their new paper, published in Sleep Health, the authors explore the prevalence of each myth and present counterevidence to clarify what’s best for health.

“Adolescents face myriad barriers when it comes to sleep, some of which are physiological and others behavioral,” said corresponding author Rebecca Robbins, a researcher in the Brigham’s Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders and a Harvard Medical School instructor. “Given these challenges, it is critical to reduce any modifiable barriers that stand in the way for young people when it comes to sleep. Our goal was to identify common adolescent sleep myths and inspire future public outreach and education efforts to promote evidence-based beliefs about sleep health.

“Caregivers and adolescents commonly turn to the Internet and social media for guidance on topics such as sleep. Although these platforms can be sources of evidence-based information, there is the chance that misinformation can proliferate on these platforms.”

The researchers surveyed 200 parents and caregivers about 10 sleep myths identified by experts. Some of the prevalent myths that Robbins and colleagues identified and deconstructed include:

• “Going to bed and waking up late on the weekends is no big deal for adolescents, as long as they get enough sleep during that time.”

Approximately 74 percent of parents/caregivers agreed with this myth. But, the researchers explain, varying sleep schedules on the weekend — also known as “social jetlag” — can worsen sleep and does not restore sleep deficits. The authors cite studies showing that varying sleep schedules on the weekend can lead to lower academic performance, risky behaviors such as excessive alcohol consumption, and increased mental health symptoms.

• “If school starts later, adolescents will stay up that much later.”

About 69 percent of parents/caregivers agreed with this myth. Robbins and colleagues cite numerous studies showing that delayed middle and high school start times resulted in significantly more sleep, with extended sleep in the morning and minimal impact on bedtimes.

• “Melatonin supplements are safe for an adolescent because they are natural.”

Two-thirds of parents/caregivers believed this myth. While melatonin has become a common supplement for adults and adolescents, longer-term studies on its use are lacking, particularly when it comes to melatonin’s effects on puberty and development. The content of melatonin in supplements varies widely. The authors also raise concerns about teens taking melatonin without medical evaluation or supervision, and without using behavioral interventions to help address insomnia.

The authors note that their study explored sleep myths among a small sample of parents/caregivers, and future studies of a larger population of parents/caregivers may help to further clarify sleep beliefs. Future studies could also include adolescents themselves as well as experts from other countries and cultures.

“Future research should aim to counter myths and promote evidence-based beliefs about adolescent sleep,” said senior author Judith Owens, a Boston Children’s Hospital physician and a professor of neurology as Harvard Medical School.

Disclosures: Robbins has served as a consultant to Denihan Hospitality Group, SleepCycle AB, Rituals Cosmetics BV, Deep Inc., and Wave Sleep Inc. Co-author Lauren Hale received an honorarium from the National Sleep Foundation for her role as editor in chief of Sleep Health (between 2015 and 2020). Co-author Michael Grandner has received grants from Kemin Foods, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and CereZ Technologies, and has received consulting funds from Fitbit, Natrol, Casper, Athleta, and Merck.

Funding: Funding for this work was provided by the NIH/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Defense.