Face to face with ancient Egyptians

Realistic mummy portraits shed light on life, death in multicultural Roman era 2,000 years ago

Images courtesy of Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Realistic portraits of the dead attached to mummies during Egypt’s Roman era have long posed mysteries that scholars are only starting to solve thanks to advances in technology. A new exhibition at Harvard Art Museums, “Funerary Portraits from Roman Egypt: Facing Forward,” breaks down what scientific investigations of these portraits reveal about life and death in Egypt 2,000 years ago.

Most of the panel paintings, plaster “masks,” and shrouds known as “mummy portraits” came to museums from the antiquities market. Few details have been recorded about their burial sites and excavations, but with the aid of specialized cameras, researchers are finding new clues.

Many mummy portraits came from Northern Egypt, in an area called the Fayum.

Photo by Mena Melad

Names and faces

The subjects were attired in clothes, jewelry, and hairstyles popular in Rome at the time yet took part in Egyptian religious traditions.

“They are living in a multicultural context just like many of us do,” said Egyptologist Jen Thum, one of the curators. “They might identify one way in one context in their social life, and one way in another.”

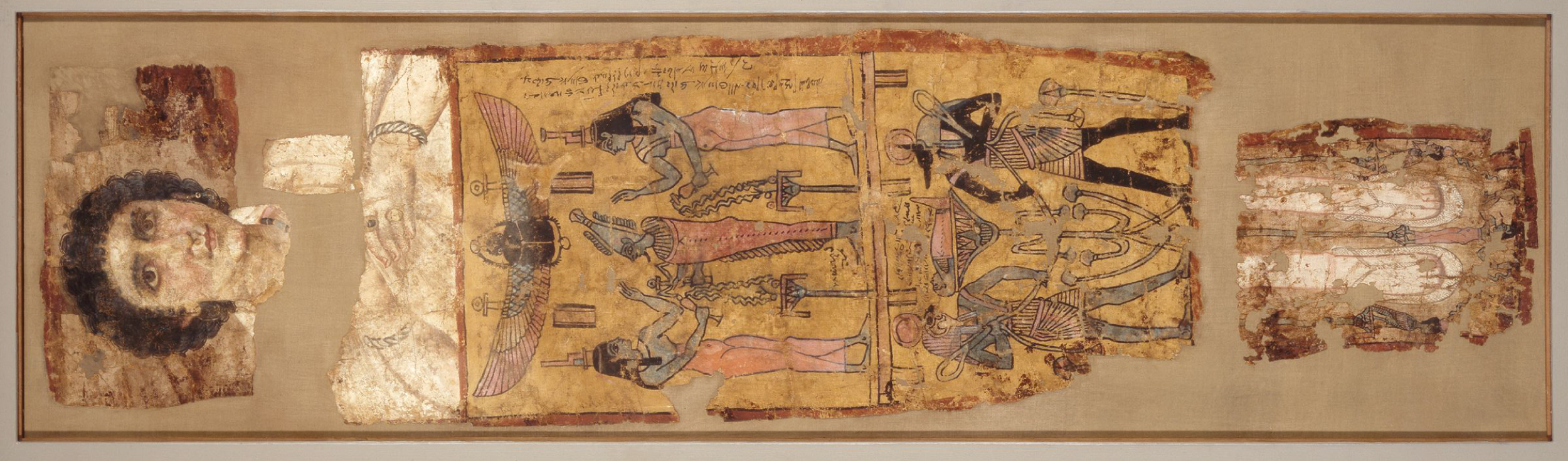

Researchers say burial shroud of Tasheret-Horudja likely dates to 1st–2nd century CE and comes from Asyut, Egypt.

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

A good example is Tasheret-Horudja, daughter of an Egyptian priest. Her portrait is the only linen shroud in the exhibit, meaning it was painted on fabric wrapped over the mummified body, unlike wooden panels and sculptural portraits, which were placed over the face and upper body (see rendering below).

The shroud fuses Egyptian imagery with a naturalistic Greco-Roman portrait of the upper body and feet, making it “kind of bilingual,” said curator Susanne Ebbinghaus.

It’s also the only named portrait in the exhibition.

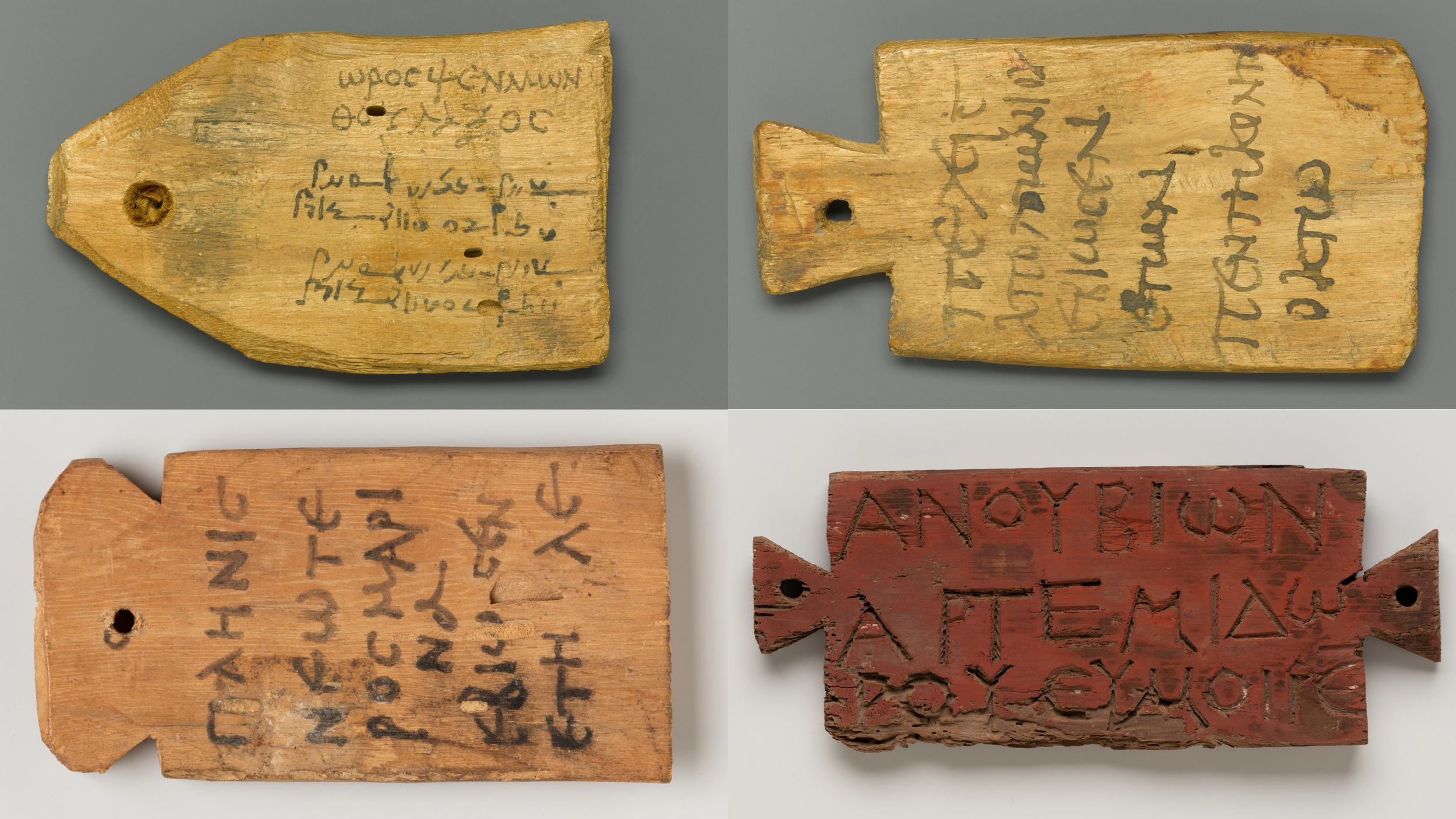

Most of the 1,000 or so mummy portraits known to survive today are separated from the remains of the people they portray. Many also are missing the wooden tags that were often attached to mummies, inscribed with names of the dead and other identifiers.

Mummy labels read (clockwise from top left) in Greek, “Horos, son of Psenmonthes, stonecutter” and in Demotic, “The Osiris Hor, son of Psenmonth, the stonecutter and priest of Imhotep”; in Greek, “Peleis, son of Apollonius. He lived 58 years”; in Greek, “Anoubion, son of Artemidoros, be of good cheer”; and in Greek, “Plenis, the younger son of Marinas. He lived 35 years.”

© Brooklyn Museum

The labels helped embalmers avoid mixing up bodies but had a deeper purpose, said Thum. “It also kind of functions like a memorial, almost like a tombstone or a stela.”

Curators borrowed several mummy tags for the exhibition, even though they don’t match up with the portraits on view.

“A lot of this exhibit is about what’s not here,” said Thum. “What can we learn from what’s left?”

Six souls, one portrait

“It has a bit of a puzzle quality to it,” when you look at it with the naked eye, conservator Kate Smith said about the composite portrait below. Thanks to technical imaging, a more complete picture is emerging.

Researchers can tell fragments were inserted into the main panel, probably to make it more desirable to art buyers. They also know from analysis of brushwork and materials that the inserted pieces are fragments from other ancient portraits.

“They’re all to be valued in that they’re all artifacts,” said Smith.

Diagram (right) illustrates which fragments are related to the main portrait and which were determined to be added.

© Harvard Art Museums

“We think that there were six people represented in this,” added associate conservation scientist Georgina Rayner.

“It’s a moment to remember that this is really a desecration,” Smith said.

© Harvard Art Museums

This fragmentary portrait of a woman, left broken, offers a counterpoint to the composite. “Still very powerful, but much of her is lost. … They’re all fragmentary in some way but she is less legible,” said Smith.

Artist’s hand

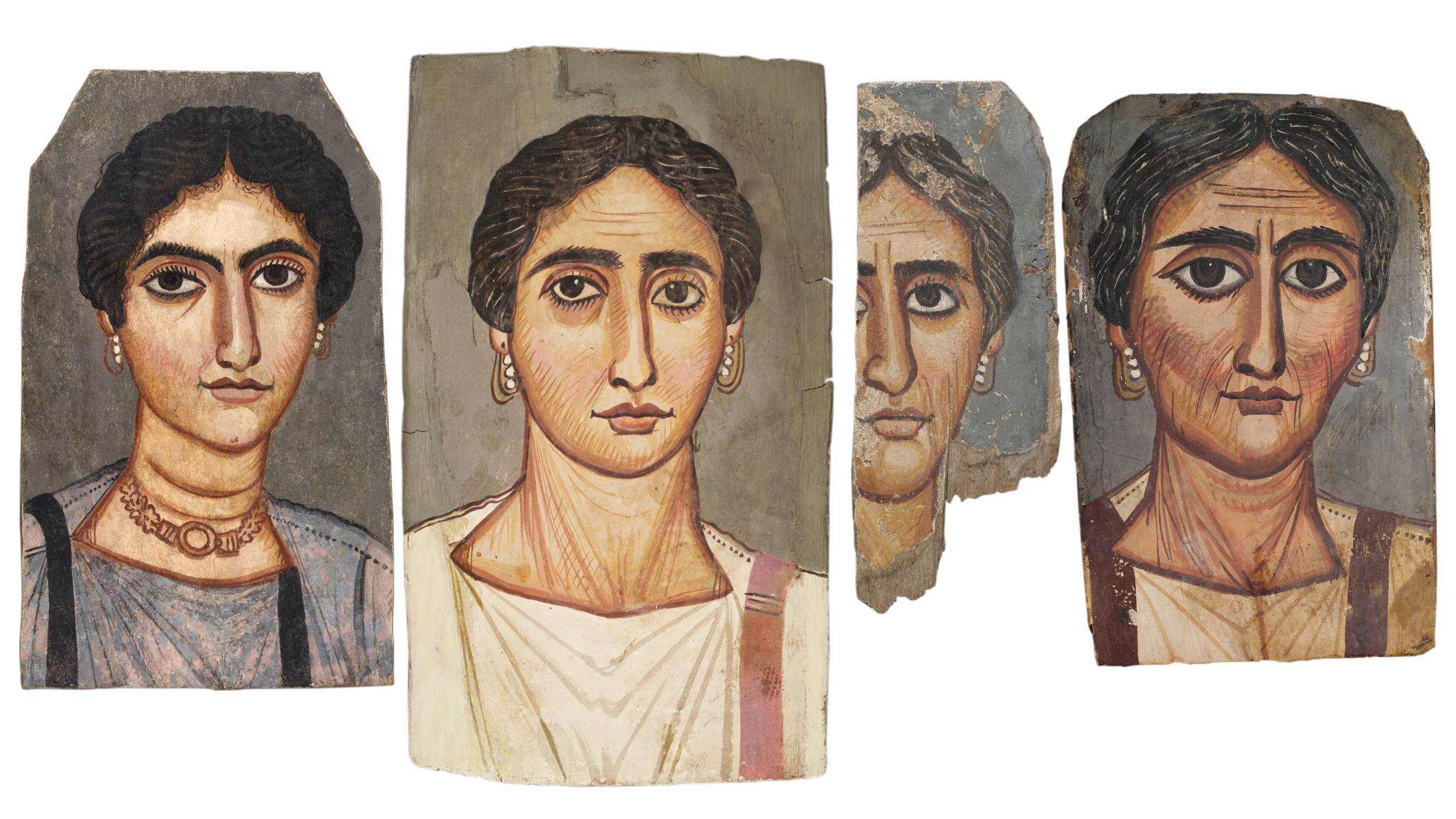

Funerary portraits were unsigned by artists, so researchers have attempted to find signatures in date, style, and materials. Some researchers attribute the four examples below to one artist or workshop.

© Smith College Museum of Art, Harvard Art Museums, Yale University Art Gallery, Saint Louis Art Museum

Character traits are rendered similarly: eyes, nose, what seems to be the same pair of pearl earrings. All were created in the more stylized tempera rather than encaustic painting style and date roughly to the same period. Researchers estimate age of portraits by how hairstyles track with trends set by the Roman imperial family.

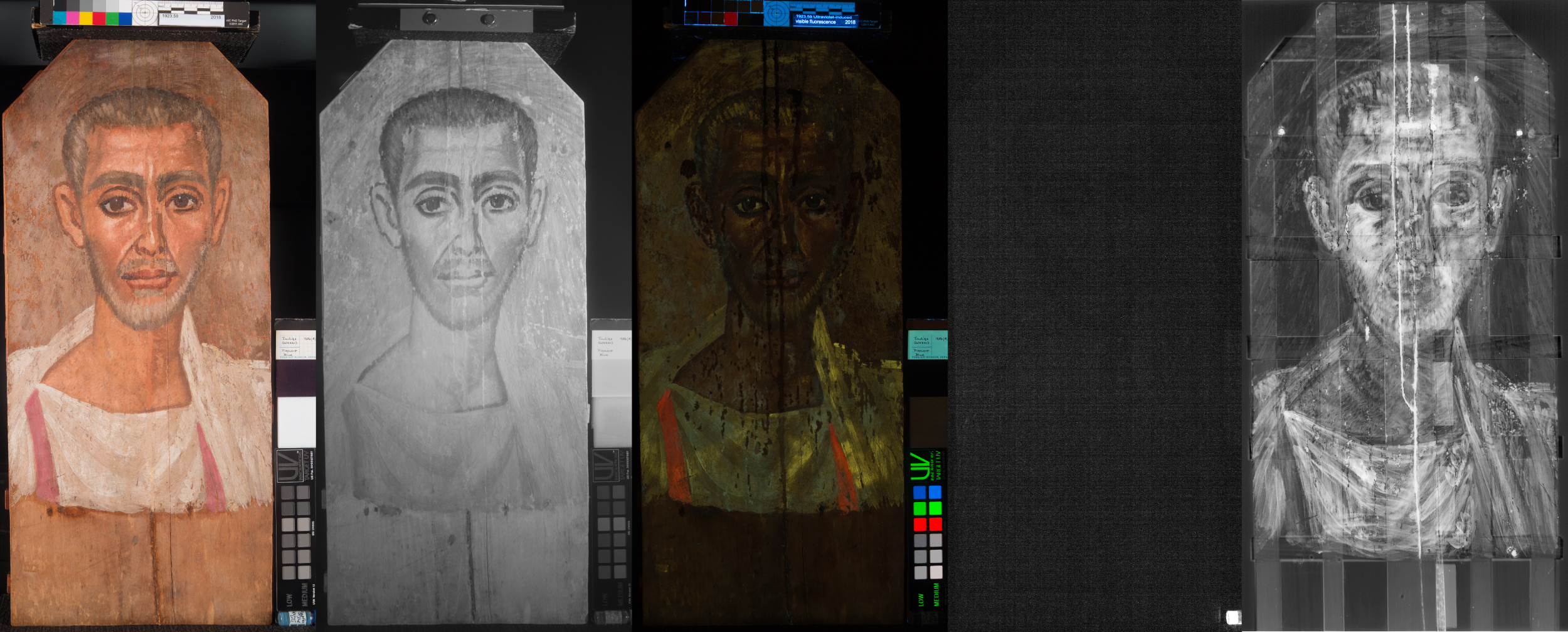

Smith, Rayner, and colleagues examined the four portraits to see whether scientific analysis would support the single-artist theory. Techniques such as pigment analysis, infrared reflectography, and ultraviolet-induced fluorescence imaging can give researchers an idea of everything from type of wood used to sequence of steps by the artist.

Results were mixed, revealing both similarities and differences in material and technique. “There are enough differences to say that it’s probably not all one person,” said Smith. “It could well be a group of people working toward a common visual goal with slightly different palettes and slightly different approaches.”

Curators Kate Smith (from left), Jen Thum, Susanne Ebbinghaus, and Georgina Rayner discuss the exhibition.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

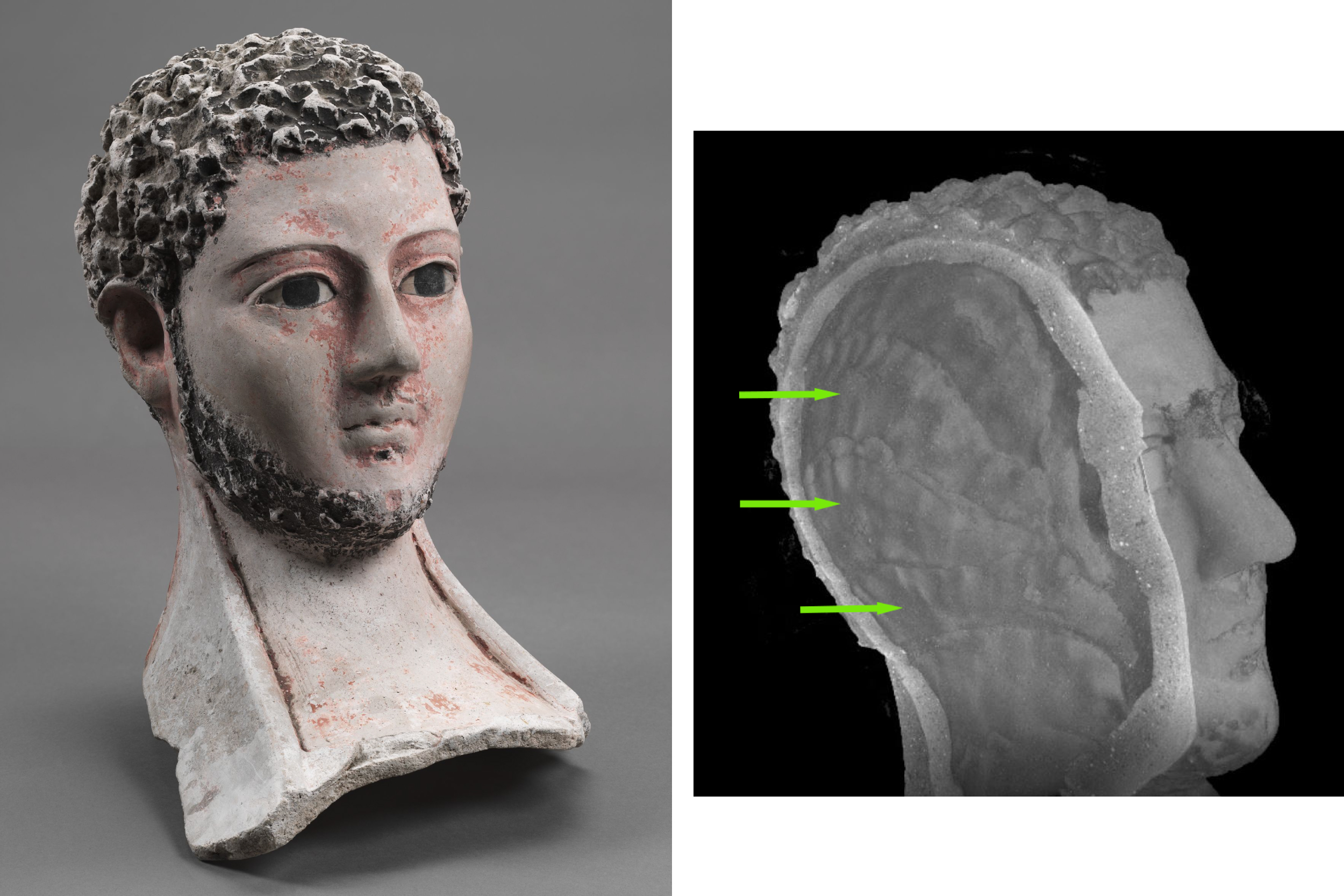

A micro-computed tomography 3D model of a plaster portrait shows the inside surface. Arrows indicate pressed sections of plaster.

Courtesy of Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems, Harvard Art Museums, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Imaging is also helping scholars understand how customized the portraits were. A micro-CT scan of this mask shows what’s likely “the fingerprints of the maker,” said Ebbinghaus.

“There was mass production, yes, but then there were also some attempts to individualize.”

Archaeologists have not discovered artists’ studios directly connected to funerary portraits. So curators created their own, drawing from the museum’s rich holdings of ancient pigments and binders. “Everything we found in the portraits is here on the table,” said Smith.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Not your pharaoh’s burial

People depicted in the portraits were upper-class, say curators. Even within the elite, burial options of varying quality were available depending on a family’s means. Burial sites ranged from pits in the sand to family tombs. “Just like in our culture, you can make a choice of how you want your loved ones to be treated,” said Thum.

While the basic Egyptian belief in preserving the body for the afterlife endured during Roman rule, gone were many of the trappings we associate with elaborate Pharaonic tombs, said Thum. “It doesn’t seem to be as important that you take things with you.”

A portrait under normal light, infrared reflectography, ultraviolet-induced fluorescence, visible-induced luminescence, and X-radiography.

© Harvard Art Museums

Were the paintings displayed while the subjects were alive? Curators say it’s up for debate but point out that many panels, like the one above, contain a blank spot designed to be tucked into mummy wrappings. “Also, these would have been really awkward to have around,” said Ebbinghaus, pointing to the raised angle of a funeral mask in the exhibition.

Another question among scholars concerns how faithfully the portraits represent the dead.

“How much of a physical likeness there was remains debated although it is interesting because what distinguishes this exhibition from others of mummy portraits is not just the focus on science but also the fact we have multiple portraits of elderly people,” Ebbinghaus said.

Reflecting the shorter life spans of the time, portraits of elderly people are rare, with only several known examples, say curators.

Compare the images by moving the slider (click or swipe).

Researchers are also finding clues to the portraits’ paths from burial ground to museums.

X-radiograph imagery of the panel above shows where metal nails or brads were used to add pieces of modern wood to form a rectangular shape that would make it more attractive on the art market. A sticker and stamps on the back trace it to Theodor Graf, an Austrian businessman who was the main purveyor of mummy portraits in the late 19th century, Ebbinghaus said.

Ultraviolet analysis of the back of the portrait below revealed remnants of resin used to attach the mummy wrappings themselves.

“It’s just a really stark reminder of what we’re actually looking at,” Smith said. “It reminds us to be respectful.”

Fragments of mummy wrappings remain attached to the back of this panel. Based on the hairstyle, jewelry, clothing, art historians date the portrait to around 130–50 CE, which is close to radiocarbon dating of the wood.

© Harvard Art Museums

More like this

In an essay on loss accompanying the digital companion to the exhibition, Kathleen M. Coleman, James Loeb Professor of the Classics, considers the grieving families responsible for these funeral arrangements.

“As viewers of these portraits, our focus is on the deceased, who look so lifelike that after leaving the galleries we half expect to run into them in Harvard Square.

“It is easy to overlook the heirs who took care to ensure the safe journey of their relatives … but we can sympathize with their grief, messy and complicated though it may have been, and reach across the centuries to imagine that sense of loss that, perhaps more than any other human emotion, binds us together.”

“Funerary Portraits from Roman Egypt: Facing Forward” can be viewed in the University Research gallery through the end of the year.

Related events

- Sept. 28 (12:30–1 p.m.) Conversations around Funerary Portraits

- Oct. 4 (2-2:30 p.m.) Gallery Talk: Funerary Portraits from Roman Egypt

- Oct. 6 (6-7:15 p.m.) “Mummy Portraits” of Roman Egypt: Status, Ethnicity, and Magic

- Oct. 12 (12:30-1 p.m.) Conversations around Funerary Portraits

- Oct. 16 (10 a.m.-1 p.m.) Materials Lab Workshop: Making Faces

- Oct. 20 (10 a.m.-1 p.m.) Materials Lab Workshop: Making Faces

- Oct. 26 (12:30-1 p.m.) Conversations around Funerary Portraits

- Nov. 9 (12:30-1 p.m.) Conversations around Funerary Portraits

- Nov. 13 (12:30-1 p.m.) Gallery Talk: Funerary Portraits from Roman Egypt

- Dec. 4 (10 a.m.-1 p.m.) Materials Lab Workshop: Making Faces

- Dec. 11 (2-2:30 p.m.) Gallery Talk: Funerary Portraits from Roman Egypt