As alarming as test scores are, reality for U.S. students is probably worse

Dramatic decline ‘just the tip of the iceberg,’ says expert worried about broken connections with classmates, teachers and deepening inequality

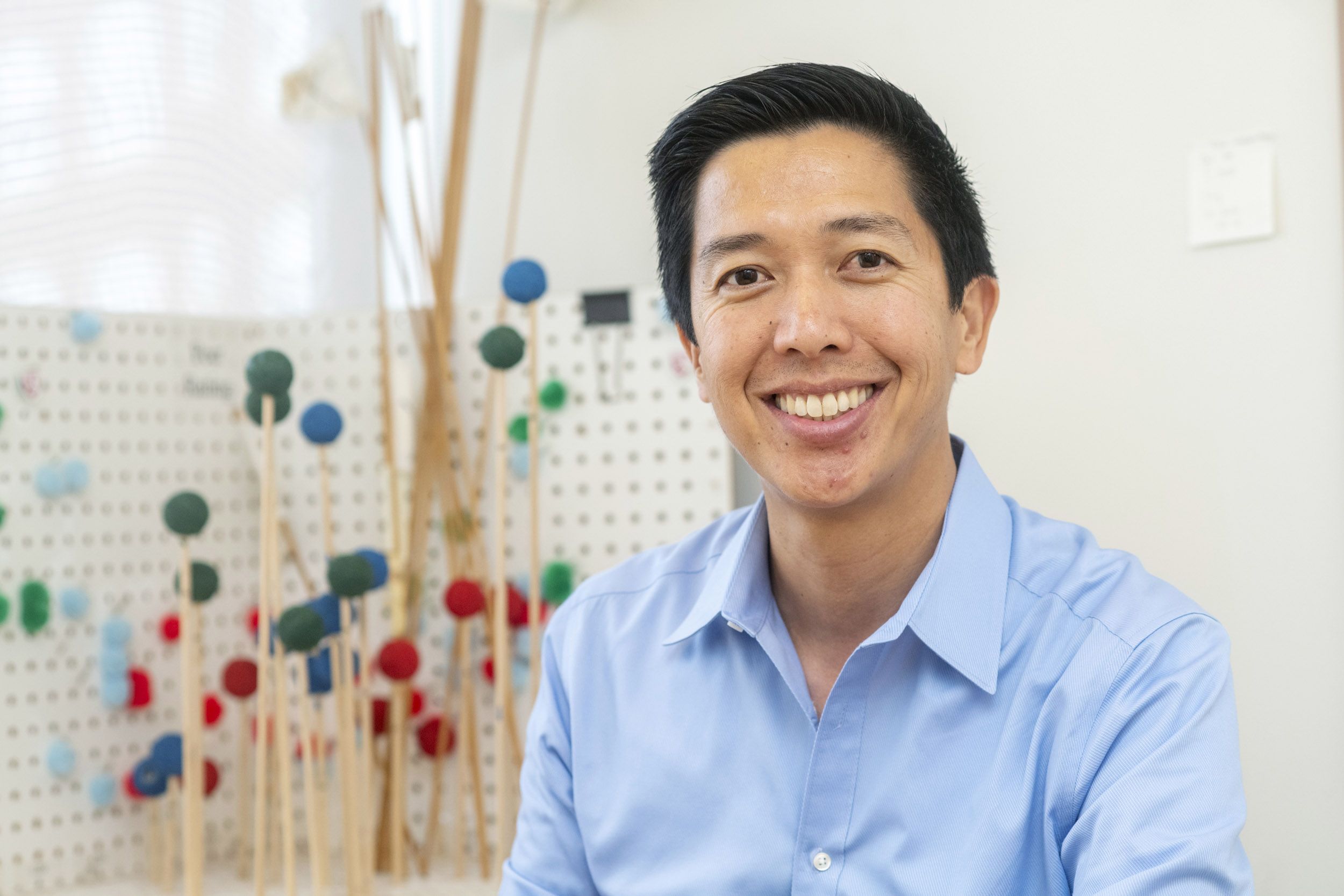

Declines in reading and math scores among U.S. 9-year-olds during the pandemic were not just dramatic but historic, according to a report issued late last month by the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Andrew Ho, Charles William Eliot Professor of Education at Harvard, previously served on the board that oversees the tests. In an interview with the Gazette, he talked about the stark inequality apparent in the results and how families, individual schools, and government can help students recover lost ground. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Andrew Ho

GAZETTE: Were you surprised by the falling scores?

HO: I was surprised by their magnitude. I was also struck by the magnitude of the worsening inequality — the extent to which disparities in educational opportunities have widened over the pandemic. To put it one way, for students at the 10th percentile, which is to say lower-scoring students, their declines were four times the declines of students at the 90th percentile. To put it another way, each point on the NAEP scale is roughly three weeks of an academic year, and the overall decline was seven points, which is roughly five months in terms of an academic school year of learning that this cohort of students is relatively behind.

But this average betrays the inequality where the decline for the higher-scoring students was only three points, or nine weeks, whereas the decline for the lowest-scoring students was 12 points, which is 36 weeks, which is almost approaching an entire academic year. This is a reminder that, for all the attention we should be giving to education, we should also be giving it strategically to the schools and the educational opportunity structures that face the greatest challenges.

GAZETTE: You have served on the board of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Can you compare the latest results to findings from past decades?

HO: From the late 1990s through the early 2000s, there was a decade of educational progress, and then from the late 2000s through the 2010s, there was, on average, an apparent leveling off of that trend, with worsening educational inequality underneath. In other words, a decade of average progress was followed by a decade of worsening inequality. What the pandemic has done, from that historical reference point, is twofold: It has erased that decade of progress in the late 1990s to the early 2000s, and it has worsened the inequality. Relative declines are substantial for every group, but particularly so for previously low-scoring students, whose educational outcomes were already showing disproportionate declines from the past decade, even before COVID.

“What the pandemic has done … is twofold: It has erased that decade of progress in the late 1990s to the early 2000s, and it has worsened the inequality,” said Andrew Ho.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: Which findings are your most worried about?

HO: While we have now one well-measured indicator of declines in educational opportunity, they are likely indicators of all the other measures that we also have experienced losses in — including social and emotional structures, collaborative structures, and the fabric of educational opportunity writ large. I’m not just worried about academic learning. I’m worried about the structures of educational opportunity and inequality that have increased over the pandemic; this is just the tip of the iceberg. I hope we can pay attention to the entire structure of educational opportunity. Academic learning outcomes are easy to measure, but also easy to overemphasize, as if students are only trying to get better at math and reading and not also trying to reconnect with their classmates and their teachers and remember how to sit still, listen, learn, and enjoy learning and playing with others.

GAZETTE: What steps are necessary at the federal and state level to close the learning gaps created by the pandemic?

HO: There was a historically large infusion of federal funding to education that was long overdue and needs to continue. Certainly, improved support of school systems is necessary, along with wise spending, which has been shown through research to be very effective.

But we should remember that the word that best describes education in the United States is local, which is to say that the decisions are often made at the district level. When I think of what state and federal responses should be, I think they can help to create a learning infrastructure — by which I mean data infrastructure. If you think about why we’re talking about this test it is because there is such a thing as a National Assessment of Educational Progress. Surprisingly, there is no such a thing as a National Assessment of Educational Equity. There’s no such a thing as a standardized measure of what goes into every school system and how every school system uses its resources. What I hope is that from this past couple of years, we can think about a learning infrastructure for schools that helps us track at a national level what all these local efforts are doing so that we can learn from all of the experimentation that is currently going on in schools, not just in terms of outcomes, but the efforts that people are putting into school systems.

GAZETTE: Can individual schools and parents do anything to help?

HO: I’m immensely hopeful and proud because of how U.S. families and schools and teachers stepped up. Without their efforts, this truly would have been much worse. As a father of two kids, I know how hard teachers and school leaders were working to do their best for our kids. I hope we can recognize that and build from those strengths; build from that resiliency to continue supporting our instructors. I also hope, as we look at this test that most people have never heard about before, that we realize that it’s providing incredibly useful information, and that we need more comparable metrics, not just for academic learning, but for many other educational inputs and outcomes.