Who is your favorite literary hero, villain?

Some of Harvard’s best-known readers, writers weigh in

As readers, we all have our favorite characters: the fictional heroes and heroines we’d love to befriend in real life, and the villains whom we long to see fail. As summer vacations allow us to return to leisure reading, we polled Harvard faculty about their literary heroes and villains and received some surprising answers.

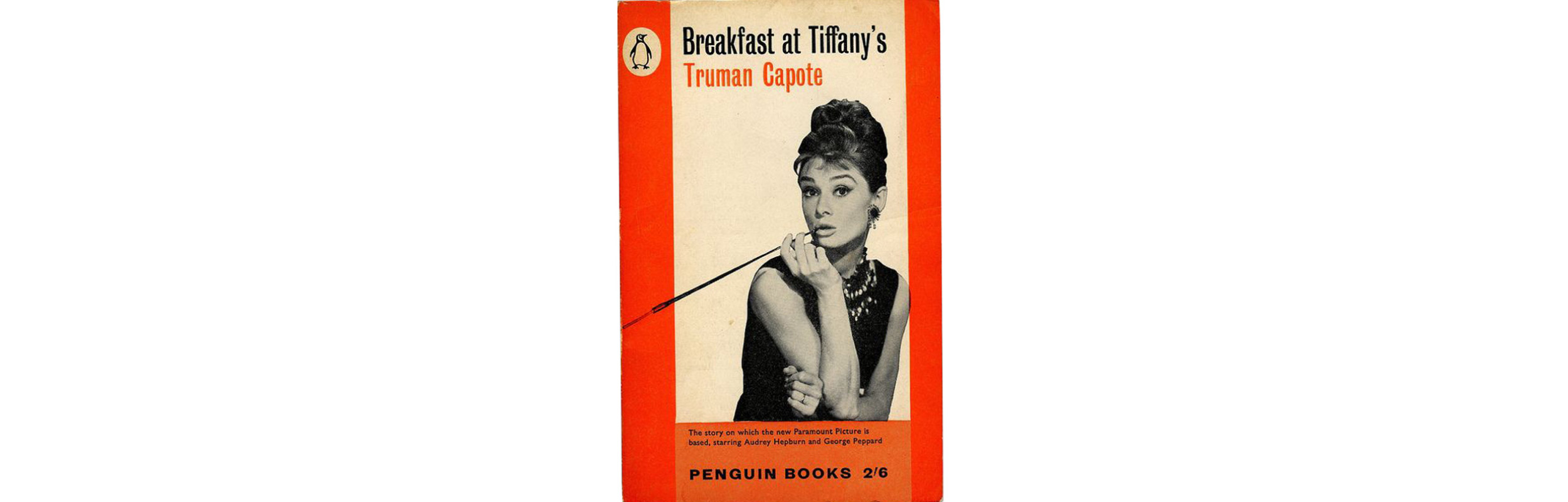

Jill Hooley

Professor of Psychology

“For me, Holly Golightly in Truman Capote’s ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ is a villain,” noted Jill Hooley. The head of the experimental psychopathology and clinical psychology program said, “How can you like anyone who abandons her cat in the street when she leaves town?”

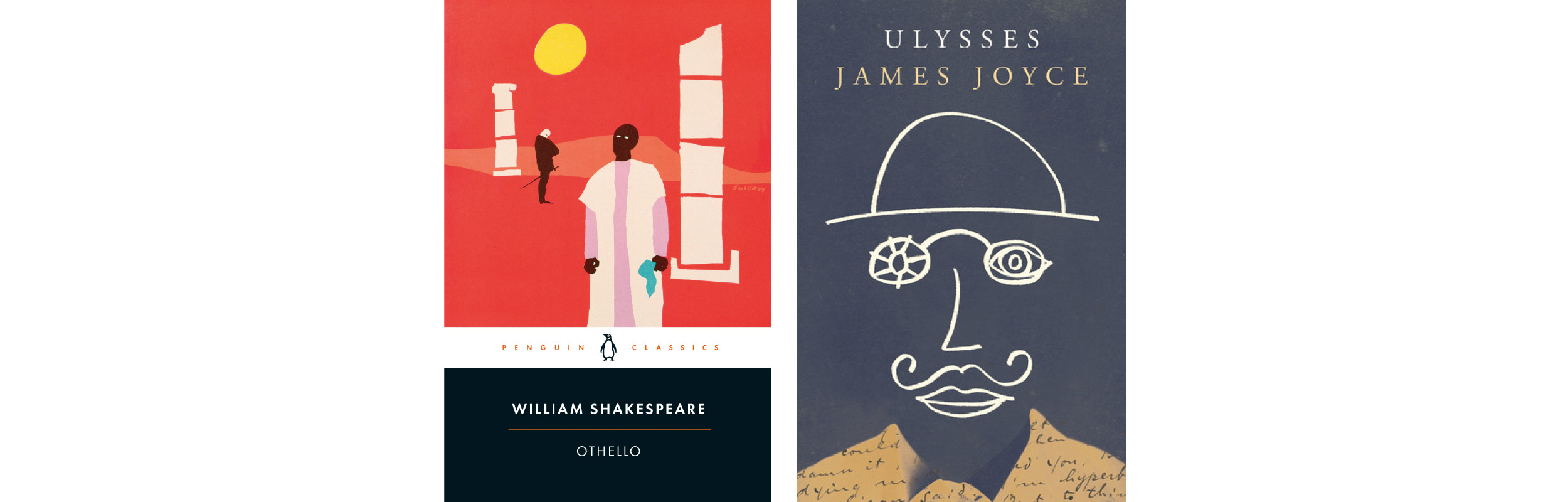

Stephen Greenblatt

John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities

Iago, the false friend who betrays Othello in Shakespeare’s play, tops Stephen Greenblatt’s list of villains. Calling him “the enemy of love and happiness,” Greenblatt confessed his heroes and villains “are on the obvious side.”

His literary hero? Leopold Bloom of James Joyces’s “Ulysses,” whom Greenblatt describes as “tolerant, curious, ever-hopeful.”

Charles Maier

Leverett Saltonstall Research Professor of History

Charles Maier finds that his discipline affects his perspective. “I’m a historian and feel overwhelmed enough by real events so that fictional heroes and villains rarely measure up to real ones,” he said. “But for a relevant hero, I’d choose Dr. Bernard Rieux, the rational and courageous Dr. Fauci of Oran, who fights Camus’ ‘Plague’; and for a relevant villain, who better than Sinclair Lewis’ Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, the demagogue in ‘It Can’t Happen Here,’ and a preternatural role model for Donald Trump?”

Jane Kamensky

Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History

Another Harvard historian, Jane Kamensky, pointed to one character as a choice in either category. “Readers will have to decide whether 64-year-old Mickey Sabbath, the protagonist of Philip Roth’s magnum opus ‘Sabbath’s Theater,’ is a hero or a villain,” said Kamensky. “Both and neither? He’s ravenous and scabrous, a man of his century’s untrammeled appetites. Sabbath’s furious, too: a Lear of the sexual revolution, frustrated by everybody else’s daughters.”

Kamensky, who also serves as the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Schlesinger Library, said: “Feminists are leery of Roth these days, but to bypass Mickey is to miss one of the greatest, vilest, realest creations of modern fiction.”

Dario Lemos

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Contemporary Spanish crime fiction gave Dario Lemos his hero: “Inspector Leo Caldas, main character of a noir saga of crimes in rainy and gray Galicia, by Domingo Villar.” In books such as “Ojos de agua” (“Water-blue Eyes”) by Villar, who died this year, “Leo has to solve complex, often twisted cases, while dealing with an elderly father who’s starting to show signs of dementia. His investigations flow slowly, often through stages that seem to lead nowhere, and have a psychological component that is influenced by the misty coastal scenery and the secretive Galician fishermen’s culture.”

David Damrosch

Ernest Bernbaum Professor

In contrast, David Damrosch went far back in time — to the second century B.C. “My favorite choice both for a villain and a hero has to be Gilgamesh, protagonist of the first great masterpiece of world literature.” The chair of the department of comparative literature explained why he both loathes and loves the Mesopotamian protagonist of the eponymous epic poem. “He actually starts out as a villain — a brash young king, oppressing his subjects, sleeping with women on their wedding night, and despoiling a sacred forest and murdering its guardian. Then the death of his intimate friend Enkidu forces him to confront his own mortality, and he returns at the epic’s end to his city, sadder, wiser, and ready to rule as he should.”

Panagiotis Roilos

George Seferis Professor of Modern Greek Studies and of Comparative Literature

“I have always appreciated heroes and villains who transgress the definitional boundaries these two categories presuppose,” said Panagiotis Roilos. “In Sophocles’ ‘Philoctetes,’ Ulysses is transformed into an untrustworthy trickster who attempts to deceive the homonymous protagonist. Ulysses believes that by acting in this way he serves a higher purpose: the victory of his compatriots at the Trojan War. Does he make him a hero or a villain? As for my favorite literary hero: Luigi Pirandello’s ‘Six Characters in Search of an Author’ exemplifies my preference for heroes who undermine established conceptualizations of heroicity.” The professor of comparative literature quotes the poet Seferis, for whom his seat is named: “Heroes walk in the dark.”

Alice Flaherty

Associate Professor of Neurology and Psychology

Alice Flaherty also had an issue with the traditional definitions of hero and villain, and chose a matched pair. “I could never pick a favorite, but here is a hero-villain pair who fascinated me recently: Philip Pullman’s ‘The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ.’ In his retelling of the Gospels, Mary gives birth to twin boys, a sickly selfless one and a robust selfish one. Their brotherly love and aggression make the reader’s opinion switch several times as to who is the angel and who the devil.” The author of “The Midnight Disease: The Drive to Write, Writer’s Block, and the Creative Brain” concluded, “In the end, the fairy tale seems more like a history, and the actual villain turns out to be someone else.”

Gish Jen

Visiting Professor of English

Award-winning novelist Gish Jen offered a different take, opting to share neither hero nor villain but instead “a true disappointment.”

“That would be Natasha Rostov in ‘War and Peace,’ who goes from a most vital, enchanting, and unpredictable girl to the most boring and conventional of women, completely ruined by motherhood (and, of course, Tolstoy),” she said.

James Simpson

Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor of English

“I had no trouble settling on my favorite villain,” said James Simpson, naming medieval European folklore character Reynard the Fox. “He’s wily and forever capable of deploying rhetoric and wit to outfox, as it were, the gullible, the greedy, and the rapacious. Not a nice guy, to be sure, and a real villain, but there is something mysteriously, inexpressibly funny about the rapier-like, mercurial, endlessly inventive brilliance of his wit, ever capable of extracting him from very tight and dangerous corners. The humor is dark but all the richer for that. He’s been a best-seller since the 12th century, when he first appeared. In French his name even replaced the word for ‘fox.’ That many million readers and speakers can’t, I hope, all be wrong.

“I took a while longer to agree with myself about my favorite literary hero/heroine,” continued Simpson. “The competition is pretty stiff, but right now it’s Echo, the victim of Narcissus’ narcissism in Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses.’ Affronted by Echo’s garrulousness, Juno punishes her with a speech handicap: Echo will be able only to repeat the last phrase she hears.”

That leads to trouble when she falls in love with the “cold and self-obsessed Narcissus,” Simpson said. “Narcissus hears something in the woods and aggressively challenges the visitant: ‘Come!’ he cries. And hiding Echo? ‘Come!’ she calls.’ The narrative underscores so very much, especially agency working within tight constraints. The story expresses more profound pathos for Echo (she ‘is seen no more upon the mountain-sides; but all may hear her, for voice, and voice alone, still lives in her’) than fury toward Narcissus. It points to the echoic, painful, diminishing voice of lyric across centuries to come. We still hear Echo’s voice.”

Such voices and their tales, both tragic and triumphant, are why we read, after all.