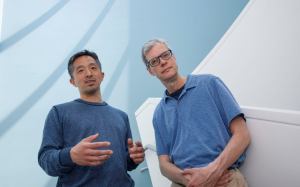

Peter Kilian (left), Nicholas Bellono, and Brittany Walsh with the piranhas.

Video by Cooper Hardee/Harvard Staff

They’re less terrifying than you think — but still, those teeth

It took some doing, but Harvard scientists brought piranhas to lab to study their feeding habits up close

Peter B. Kilian remembers leaving Logan Airport with Brittany Walsh in mid-February and having a single thought as he looked left and right at other drivers: “They don’t know our car is filled with piranhas.”

Known for their fearsome teeth and bloody B-movie feasts, the fish are illegal to own in Massachusetts. Kilian wasn’t aware of that when he decided that studying their predation behavior would be a “cool” project for the Bellono Lab, which investigates how molecular and cellular adaptations lead to unique behavioral functions in organisms.

But he didn’t let it stop him. And before too long, with the necessary local approvals and a piranha permit for the lab in hand, he and Walsh, a fellow research technician in the lab, found themselves scrambling on short notice to meet a freight plane at Logan. After they loaded multiple boxes containing 20 caribe piranha into Walsh’s Honda CR-V, it was time to plan the actual science.

Researchers will study the temperaments of two species native to the Amazon — caribe and red-bellied piranha, which the lab plans to add later this year. The group want to determine if one species is more aggressive than the other and if they can parse out this behavioral difference by looking at blood, hormone levels, and gene expression.

The work is just starting, but already, Kilian, who’s leading the research, can tell you that the fish aren’t as terrifying as their reputation.

“They’re not apex predators,” he said. “They’re not regularly hunting in packs taking down healthy large animals. They’re very skittish when we have to put our hands into the tanks. In terms of where they lie in the wild, they’re relatively low on the totem pole. They’re prey species.”

The fish usually range in size from 8 to 12 inches and rarely grow larger than 2 feet. They have saw-edged bellies, blunt heads, and razor-sharp teeth.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Piranha predators include Amazon river dolphins, herons, and crocodile-like yacare caimans. The fish usually range in size from 8 to 12 inches and rarely grow larger than 2 feet. They have robust, narrow bodies, saw-edged bellies, blunt heads, and, of course, razor-sharp teeth. Despite the teeth, most piranha species are scavengers and some are even vegetarians. They have a preference for prey smaller or just slightly larger than they are.

The Bellono Lab’s work centers around feeding, specifically feeding frenzies, which is when the fish converge on a wounded animal and, well, feast. A frenzy involving hundreds of piranhas can reduce prey to bone in a matter of minutes.

Caribe piranha are thought to be more aggressive than their red-bellied counterparts. Kilian wants definitive proof. In experiments, he will be looking closely at how quickly the fish eat their prey, how many are involved in an attack, and how densely they group before making their initial strike.

The piranhas are fed a fatty, protein-rich fish called capelin. For regular feedings, researchers cut the frozen fish into small pieces and toss them into the tank. When they do behavior experiments, they thaw the whole fish and suspend it in the tank. Then they observe.

The piranha usually start with a few bites, targeting the eyes and tail to immobilize the capelin as if they were in the wild. This all looks pretty orderly and calm, if the piranha are well fed. When they are hungry, it quickly becomes a frenzy.

“What I’m interested in is if this group feeding happens because of social cues between the different fish or if there’s some sort of chemical signaling between the fish that cause it or if it’s purely a result of if they’re hungry,” Kilian said. “We’re hoping to be able to do some type of computer-aided tracking of the fish to really get at subtle differences in the frenzy in behavior.”

Besides the fact that she and Kilian are both animal lovers, this kind of project rewards the full-time effort of managing the logistics and animal care behind science, Walsh said.

“I have often thought about making a sign for the back of my car: Something like, ‘Please don’t tailgate me, I have splashing water in the back’ or ‘Fish Onboard.’”