Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

How consequential life grew from dying heart

Childhood transplant gave Jon Hochstein a second chance, guides his next steps to Boston Children’s

This story is part of a series of graduate profiles ahead of Commencement ceremonies in May.

When Jon Hochstein learned that he had matched at Boston Children’s Hospital for his medical residency program, he let his family know. Then he told his other family — Christopher’s family.

“He texted me as soon as he got word that he got his residency there in Boston,” said April Hough, Christopher’s sister. “He texted me, ‘I got Boston,’ and [it’s important] just to know that, just to know that such a huge part of my brother lives on and allows this human to continue to do amazing things.”

Hochstein is graduating this spring from Harvard Medical School, but 23 years ago he was a 4-year-old lying in a bed at Salt Lake City’s Primary Children’s Hospital. It was February 1999, and Hochstein had been there for months, his heart failing after what had seemed a routine case of the flu. His family was growing desperate. He kept getting weaker and needed a heart transplant, but weeks had passed and no heart had become available.

“Seeing your son get last rites,” Hochstein’s father, David, said. “Yeah, there were a few times when I thought we might lose him.”

The day before, Christopher Brazell had been crossing the street in front of his school in Wendover, Utah, when a pickup truck hit him. He was airlifted to Primary Children’s, where the doctors told his mother, Elizabeth Tilly, that he wasn’t going to make it. They asked whether she would consider donating his organs, and she initially refused. But as she walked the halls of Primary Children’s, wrestling with her thoughts, she saw a boy in bed, his small feet sticking out from under a blanket. When she asked what was wrong, a nurse told her he was waiting on a heart transplant. That changed her mind.

The two families never met in the hospital. Hochstein recovered from the surgery and went on to what he describes as a largely normal childhood. He had to take anti-rejection medication but was able to run and play with his younger brother, Mike, and friends from school. His mother, Barbara, insisted he take responsibility for his health, Hochstein said, and taught him to swallow pills at age 6, and, a few years later, fill his own pill containers. The family insisted that he was neither fragile nor suffering, but rather blessed. It was an attitude he absorbed, one that helped him through the larger challenges he would face as well as the heightened daily uncertainties of a transplant recipient.

“He was active; he did things; we went places. We always pushed him to try things,” said Barbara Hochstein. “We did not try to keep him in a bubble. We really tried to embrace it as the gift that it is, as opposed to being very protective.”

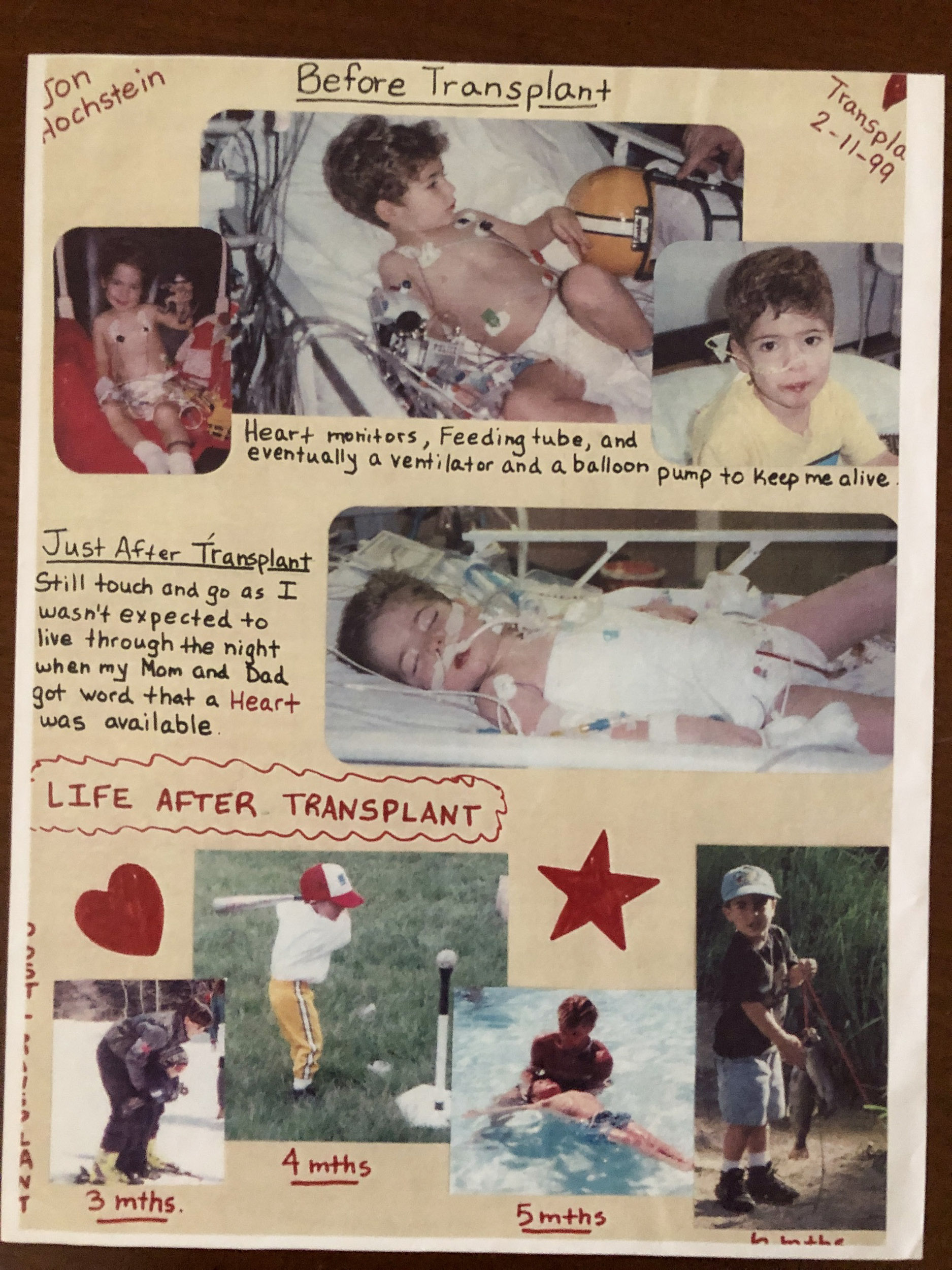

In a collage, Barbara Hochstein chronicles her son’s childhood before and after his heart transplant.

Courtesy Barbara Hochstein

Hochstein was one of the lucky ones. Every day 17 people die waiting for an organ transplant in the U.S., according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Transplantation. The unit oversees organ and cell transplantation systems across the nation, including the distribution of organs and the waiting list — which has 106,000 prospective recipients on it.

Though Hochstein was healthy for much of his childhood — he even rode the bench for his high school football team — he did have serious episodes. He was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at age 9, recovering after months of treatment. A few years later, a friend of Hochstein’s bragged to his mom that he’d beaten Hochstein for the first time in a school-sponsored run. When word got back to Barbara — always alert for signs that might indicate heart trouble — she brought him in for tests that revealed his body was rejecting his donated heart, a frightening development that was resolved when his doctors switched his antirejection medicine.

Rather than prompting him to avoid hospitals, Hochstein’s experiences made him determined to be part of the health care system that had been so vital to him, and to help others as he had been helped. He did well in high school and was accepted to Johns Hopkins University, where he studied biomedical engineering. After graduating, he entered the Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology Program, which allowed him to work on medical technology — he built a control system for a single-ventricle heart-assist device — while earning an M.D.

In the fall of 2019, when Hochstein was in his second year at HMS, his father’s workplace approached him to see whether they could make a video about his story. The Pentagon Federal Credit Union was creating a series highlighting stories of the organization’s members. The woman in charge offered to try to find the donor family — the Hochsteins had tried before and failed — and to put them in touch.

She succeeded, and the two families came together in January 2020 at Hough’s home in upstate New York. Everyone was nervous, Hochstein said, and almost everyone cried at some point. Jon brought along his stethoscope, and April and her mother both listened to Christopher’s heart beating in Jon’s chest.

“It almost feels like he turned our pain into his passion with pursuing his medical degree,” Hough said. “Meeting him was pretty emotional. It was healing.”

Hough said it was doubly so for her mother, who still grieves for Christopher.

“I think it definitely gave her some peace,” Hough said. “I think she needed that. She needed to know that she had [made the right decision], and Jon just reaffirms that for her by being such an incredible human. Her son didn’t die in vain. Jon’s going to uphold his legacy and do amazing things with it.”

“That’s really why I’m here, that’s really why I’m doing what I’m doing: getting to share with families of kids who have to get a transplant.”

Jon Hochstein

When asked whether Christopher’s gift creates pressure on him to succeed, Hochstein falls back on his Roman Catholic faith, saying he feels called not to success but to service, and to give back.

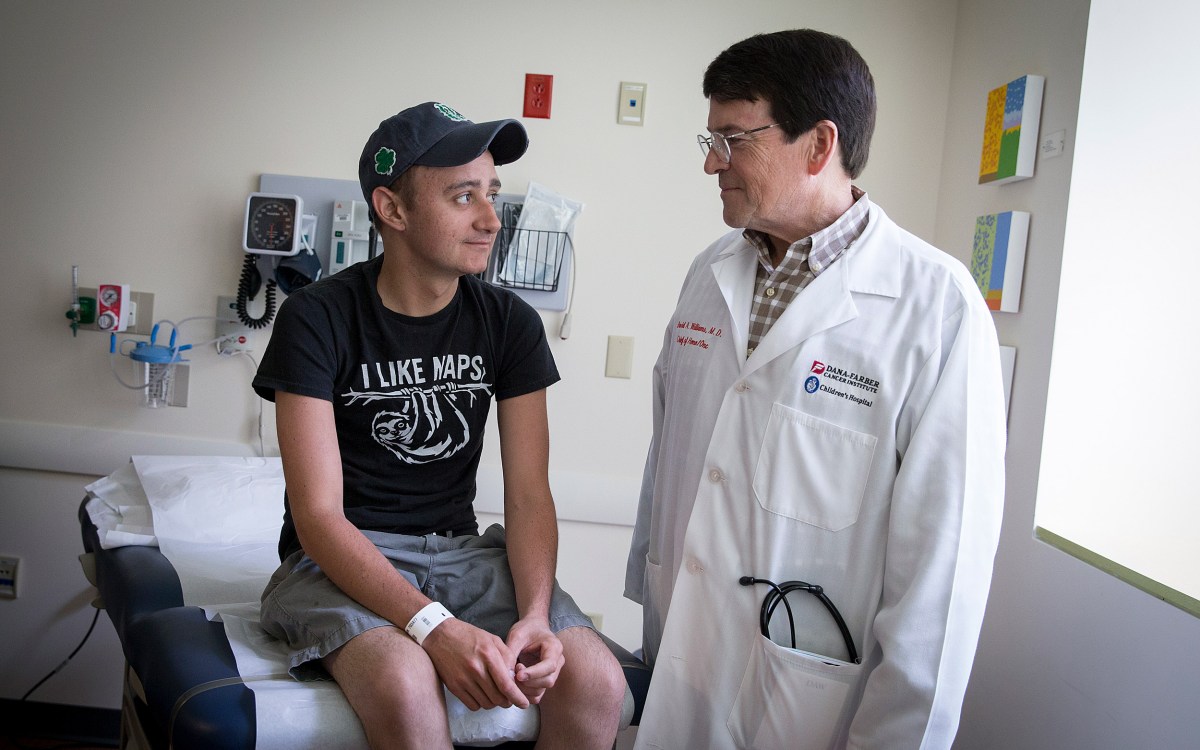

Hochstein wants a career with a lot of patient interaction, so his own experiences might help those facing health challenges. Today, he’s looking forward to starting a three-year pediatric residency at Boston Children’s Hospital in June.

“Some people don’t like talking about their experiences, and that’s fine,” Hochstein said. “For me, it felt so natural, and for many people, for many families, it’s been an essential thing to the relationship that I have with them. That’s really why I’m here, that’s really why I’m doing what I’m doing: getting to share with families of kids who have to get a transplant.”

Hochstein recalled one teenage transplant patient who was bristling with questions, which all boiled down to wanting to know how his life was going to be.

“I told him, life’s pretty normal,” Hochstein said. “We talked for hours, actually. He asked various questions about various things, everything from dating to feeling your heart in your chest, and what changes over time. The message I told him was the same that my parents told me: It’s going to be different at times for you compared to other people, but you’re going to get to do a lot of the things you want to do, and most likely everything you want to do. There might be times you don’t, but for the most part, your biggest limitation is not having grapefruit (which interacts with some antirejection drugs). And from what I hear about grapefruit, it’s pretty lame.”

Hochstein concedes there is more uncertainty in his future than typical for a soon-to-be medical school graduate. When he got his heart transplant, the average recipient lived 10 years post-transplant, a figure that has since been pushed to 20. Hochstein said he recently heard about someone marking 30 years post-transplant by running a marathon, a celebration that appeals to Hochstein’s inner athlete. That, together with the constant advance of medical science, is encouraging, but Hochstein also understands that antirejection drugs take a toll on recipients’ organs.

“I don’t know what the future holds. I don’t know if I’ll make a good ventricular assist device or make transplant better,” Hochstein said. “But I do know for those people, patients, that I get to talk to, hopefully they’ll get to see life through a lens that makes them not identify with their illness but integrate it into their reality.”