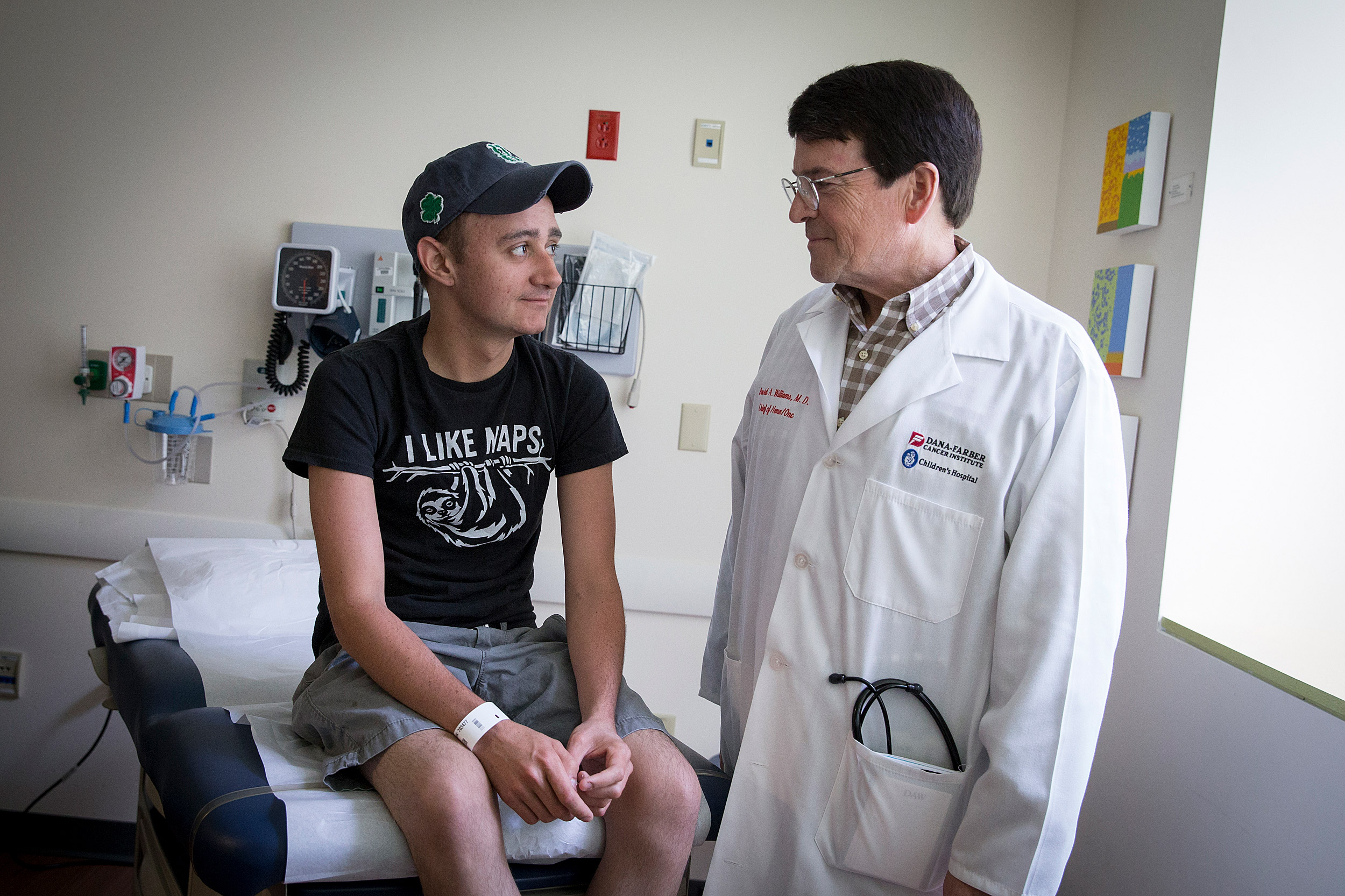

In late 2015, Brenden Whittaker was the first subject in a CGD gene therapy trial at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. He is with David A. Williams, the Leland Fikes Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Gene therapy was a ‘last shot’

Young man, who rebounded after being deeply sick, shifts his sights from being helped to aiding others

Brenden Whittaker didn’t agree to gene therapy lightly. But he had been so sick for so long that the risk of the first-time-ever procedure would be worth it if that meant finally getting well.

“I really didn’t have any other options, health-wise,” Brenden said. “I’d been sick for four or five years. They’d done countless tests, countless treatments, and nothing was working. This was really, honestly, one of my last shots at getting healthy.”

The antibiotics that had been the young Ohio man’s ally against infection were finally failing, and doctors had been increasingly resorting to surgery, cutting out an infected lobe of his liver, half a right lung. Though the surgeries worked, removing the infection along with tissue, by late 2015 Brenden, his doctor, and his mother, Becky Whittaker — an oncology nurse who had guarded his health since his infancy — knew there were only a few bullets remaining in that particular gun pointed at solutions. Infection would keep returning, and he’d eventually run out of body parts to sacrifice.

Becky said that 2015, before the gene therapy, “was absolutely a horrible year. And I really, honestly, didn’t see him living much past that, the way that things were going.”

Since birth, Brenden has struggled with chronic granulomatous disease, or CGD, a rare immune disorder that affects the function of infection-fighting white blood cells called neutrophils. The condition changes the killing chemistry that occurs inside the cells and renders ineffective the engulf-and-destroy strategy they employ against the body’s invaders.

In late 2015, Brenden became the first subject in a CGD gene therapy trial at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. The trial, which sought to correct a dysfunctional gene that causes the disease, was led by center president David A. Williams, the Leland Fikes Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital’s chief scientific officer and senior vice president.

By all accounts the therapy worked. The three years since he was infused with his own corrected blood stem cells have been Brenden’s healthiest since 2009, when a series of infections began that robbed him of his junior year in high school, prompted surgeries, and, ultimately, led him to enroll in the trial.

Though his health hasn’t been perfect, he has fought off the occasional cold or flu with little more trouble than other sufferers, to his own and his mother’s relief.

“Each day that he’s free of infection, he’s able to go to class, he’s able to work at his part-time job, he’s able to mess around playing with the dog or hanging out with friends,” Becky said, “is a day I truly don’t believe he would have had beyond 2015 had something not been done.”

While the treatment has had the hoped-for physical effect, it’s had a mental impact as well. After years of illness punctuated by long nights when he wasn’t sure he’d have a next morning, the therapy has opened Brenden’s future for him.

“I didn’t have any kind of plan for the future,” he said of his mindset before the gene therapy. “I didn’t think I was going to need one. I was more focused on the ‘right then’ — getting healthy right then. … I’d never thought that long-term before because I’d been sick for so long.”

In the three years since the treatment, Brenden has worked toward an associate’s degree in health sciences at a nearby community college. He hopes to graduate this spring, completing academic work that he began before the gene therapy but that was repeatedly delayed because he kept getting sick.

Now 25, Brenden plans to transfer to Ohio State in the fall for a bachelor’s degree program. After that, he said, medical school is a possibility.

“Just being the patient for so long,” he said, “I want to give back. There are so many people who’ve been there for me — doctors, nurses who’ve been there for me [and] helped me for so long.”

From “fatal” to “chronic” to “cured”?

CGD is relatively rare, affecting just 1,500 Americans. Once called “fatal granulomatous disease,” the development of modern antibiotics transformed what was a certain killer into a lifelong battle against infection. Today, physicians guide CGD patients toward prevention as a primary defense. Patients typically take preventive antibiotics and interferon injections to boost their immune systems and keep infections from taking hold in the first place.

More like this

The strategy works, though imperfectly enough that the lives of CGD patients — half of whom don’t live beyond age 40 — are often punctuated by repeat hospitalizations to combat bouts of serious infection and development of the “granulomas” for which the condition is named. Granulomas are clumps of infected tissue that result when the body tries to wall off infections it cannot defeat. In severe cases, the granulomas themselves can cause problems, obstructing digestive passages and other critical pathways in the body.

When antibiotics no longer do the job, some patients receive bone marrow transplants, which can generate functioning neutrophils from a donor’s blood stem cells. The transplants, however, carry the risk of graft-versus-host disease, in which the transplanted cells attack the host’s tissues. That makes it critical that donor and patient are closely matched. It also means that for some, like Brenden, a suitable donor won’t be found.

Boston Children’s Hospital has a long history with CGD. The first diagnostic test for the condition was developed there in the 1960s by Robert Baehner, a fellow in the hematology/oncology program who later became Williams’ medical school research mentor. In 1986, Stuart Orkin, today the David G. Nathan Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics at HMS, identified the gene whose mutation confers CGD. The mutation in an individual gene makes the condition a promising gene therapy candidate because, unlike diseases traced to multiple genes, it provides a clear target whose correction could, in theory, mean a cure.

“When you talk about a cure, you’re talking about decades rather than years, so I think it’s too early to tell,” said David Williams, Boston Children’s Hospital’s chief scientific officer and senior vice president.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Brenden was the first patient enrolled in what became a nine-patient, four-center trial that also involved patients at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Maryland, the University of California at Los Angeles, and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London.

The trial, funded by the NIH and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, was staged, with treatment of subsequent patients dependent on the outcome for those before them. Brenden went first and, in December 2015, doctors took a sample of his blood stem cells and sent them to a cell manufacturing facility run by Professor of Medicine Jerome Ritz at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. There, an engineered virus inserted a corrected copy of the malfunctioning gene into the cells’ DNA.

Researchers then multiplied the engineered cells to create a population of Brenden’s own cells that could be transfused back into him. Brenden, meanwhile, had undergone chemotherapy to reduce the population of malfunctioning cells and create a niche in his bone marrow for the new ones.

After the transfusion of corrected cells, Brenden returned to Ohio, where he remained isolated at home for three months as the new cells multiplied and his immune system rebooted. The result of all this, Williams and other investigators hoped, would be that at least 10 percent of the resulting neutrophils would function normally, enough so that Brenden’s immune system would provide protection similar to that of a non-CDG sufferer.

The results exceeded expectations. Months after the transplant, tests found roughly half of Brenden’s neutrophils worked normally, clearing the path for the second subject to begin treatment.

Of the trial’s nine patients, two died of illnesses related to their CGD but unrelated to the trial, Williams said. Their deaths, he said, are an unfortunate function of the fact that the people recruited for clinical trials are often very sick, with few remaining options.

“Unfortunately, these kinds of early trials often take patients in dire straits, so sometimes you have bad outcomes related to pre-existing conditions,” Williams said.

Williams said the remaining enrollees have seen similar results to Brenden’s, with improved health and functioning neutrophil counts above the trial’s 10 percent target. In addition, none have shown signs of a negative side effect seen in earlier trials, a preleukemia condition called myelodysplastic syndrome.

“We’re able to reconstitute the activity that’s missing in these neutrophils,” Williams said, “and the activity levels are substantial enough that they appear to protect from infections of the type you get if you’re a CGD patient.”

Though the therapy has proven effective, questions remain as to its durability. Previous CGD gene therapy trials also saw improvement in the body’s ability to fight infection, but they faded over time. Though the effect in the trial’s oldest patient — Brenden — has shown no sign of fading, Williams said it’s nonetheless premature to call it permanent.

“When you talk about a cure, you’re talking about decades rather than years, so I think it’s too early to tell,” Williams said. “The longest patient is now [Brenden] … with stable engraftment of those genetically modified cells, so it’s going to be a while before anyone can talk about permanent cure. But the data so far are quite encouraging that the effectiveness is stable over time.”

That uncertainty is one reason trial subjects will be followed for 15 years. It’s also something Brenden said he has accepted, part of the one-day-at-a-time philosophy he honed during the ups and downs of life with CGD.

“I’m not fearful of it coming back,” he said. “I accept and understand that it can. I knew that when I signed up for this. Fear was definitely part of it [living with CGD], but then, after a while I kind of got used to the fear. I wasn’t really afraid of dying anymore because I’d been there. I’d been to the point of having 106-degree fever for two weeks, lying in a hospital bed, planning my funeral.”

If the gene therapy stops working, he added, “I’m not going anyplace new … It’s not like I’m going to get a new disease or illness. It goes back to the old normal.”

Steps on a path to the future

Despite that hard-nosed view, hope for a cure is nonetheless part of the trial. After all, the long-term promise of gene therapy lies in the prospect of treating genetic diseases at their roots, curing them once and for all. One of Brenden’s doctors, in fact, has already seen enough, writing in case notes, according to Becky, that he considers Brenden’s improvement “to truly be a miracle of modern medicine” and “that it would appear that he is cured.”

Permanent or not, the improvement has lasted long enough to cause very real changes to Brenden’s life — changes that don’t go unnoticed by former teachers, youth group leaders, and others who knew a kid who was constantly sick, getting sick, or recovering from being sick, Becky said. When they ask after him and she describes the young man taking college-level courses with an eye on medical school, she said their surprise is apparent.

“They can’t possibly imagine what I describe now, because it’s just not the person that they knew: low energy, not a lot of effort,” Becky said. “He and I talked and it’s about going through a time of illness and then another illness and another illness and getting to the point of thinking, ‘What’s the point?’”

Brenden has also noticed the change, Becky said, not just in himself, but also in how people react to him.

“Something came up — I don’t remember what — and we were discussing how to handle it. He said, ‘In the past, this is what would have happened.’ And I said, ‘Brenden, people are reacting to you as a healthy adult. The expectations have changed,’” Becky said. “‘People are responding to you as if you are going to have 60, 70 more years on the Earth and they’re expecting a different kind of participation, contribution, than when you were a sick kid.’”

Gene therapy’s expanding promise

The rigors of gene therapy wouldn’t be Brenden’s first choice for CGD patients whose conditions are controllable with antibiotics, but, if the therapy is ultimately approved for broad use, he believes it should be made available to those seriously ill with repeat infections.

Becky, drawing on her experience as an oncology nurse at Ohio State’s James Cancer Hospital, said she’d actually prefer gene therapy over bone marrow transplants. She’s seen too many transplant patients struggle with graft-versus-host disease, trading one problem for another. The advantage of gene therapy, she said, is that because it uses the body’s own cells, it eliminates entirely the risk of rejection.

Results of the CGD trial have been positive enough that Orchard Therapeutics, on whose scientific advisory board Williams sits, plans to conduct a registration trial for the treatment. If successful, the trial would lead to FDA approval for broader use.

If it gains FDA approval, the CDG treatment would be the latest in an expanding toolbox of gene-based treatments coming to market after decades of research and development. At the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center alone, therapies are being developed for hemophilia, severe combined immunodeficiency (aka bubble boy syndrome), thalassemia, the brain disease adrenoleukodystrophy, and spinal muscular atrophy.

In addition, a recently developed treatment for sickle cell disease, which affects millions around the world, is promising enough that in December it attracted a $1.5 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The grant will support further development of the therapy with an eye toward use in low-infrastructure, developing world settings.

“I think it’s very clear that this [gene therapy] is becoming a part of our therapeutic armamentarium, for still a limited number of diseases, but an ever-expanding number of diseases,” Williams said. “I’ve been doing this for 30 years and I’ve always been pretty sanguine about how things are moving into the clinic, but it’s a very, very hopeful time right now.”

This trial was funded by the NIH and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.