What’s it take to be astronaut?

NASA picks emergency-room doctor, researcher, Afghanistan vet pilot, Ironman triathlete Anil Menon for mission training

Anil Menon scaling Mount Vinson, Antarctica’s tallest peak.

Photos courtesy of Anil Menon

They wheeled in a gunshot victim. It was Anil Menon’s first trauma case as resident in charge at San Francisco General Hospital. The young physician paused for just a second, then fell back on his training — airway, breathing, circulation — and swung into action, delivering directions to his team.

“I remember there being about 20 people in the room, all staring at me, waiting to hear what I had to say,” Menon said. “But I had studied a lot, and I had trained for this.”

They worked through the initial evaluation and discovered the gunshot had caused pneumothorax, air trapped between the patient’s lung and its encompassing membrane, constricting the lung’s ability to expand. Menon got a chest tube in, then sent the patient to the surgical ICU.

Menon, 45, a Harvard alum who was named a member of NASA’s latest astronaut class in December, has made a career out of managing stressful situations. Since leaving Harvard College in 1999, he graduated from Stanford Medical School, completed a residency in emergency medicine, a fellowship in wilderness medicine, and served as a NASA flight surgeon, overseeing the health of those flying to space. He joined the Air National Guard, became a pilot, and supervised medical operations — sometimes under fire — on search and rescue helicopters in Afghanistan.

When the earthquake struck Haiti in 2010, he was there. A year later, when a vintage P-51 fighter crashed at the Reno Air Show, he helped injured spectators at a nearby hospital and followed the medical response plan he helped developed in advance as part of his Guard work. In 2015, when a quake struck Nepal, he was in northern India to support an adventure race and instead took a taxi to Kathmandu to help. He has provided aid to climbers at Mount Everest base camp, drivers at the Indy 500, and contestants racing across the Sahara Desert. And now Menon wants to do it all in space.

“[Menon] took [organic chemistry], at least according to what is now probably legend, and he didn’t take notes. He just sat there and learned organic chemistry. With his mind. That was frustrating to hear.”

Baratunde Thurston ’99

“If I get assigned to the ISS, it will largely be doing research. That’d be a really fulfilling thing for me to do,” said Menon, a neurobiology concentrator at Harvard who cut his teeth in research at a lab at Massachusetts General Hospital. “[But] I would say my aspirations are always as far as possible. If given the opportunity to fly to Mars, I would fly to Mars. The next big step for NASA is to launch the Artemis Program in February and then to land on the moon with the human lander system and to sustainably have a presence there. Any of those opportunities I would be overjoyed to do.”

Menon and NASA’s intense, always-prepared culture seem an apt fit. When asked how he keeps cool in the kind of stressful situations that most people hope they’ll never encounter, Menon said he trains, and trains some more. That way when the situation arises, even for the first time, it feels as if he’s been there before.

“These remote medical skills are some of the things that hopefully we’ll be able to lean on and help NASA with, because our overall goal — my goal — is how do you take those kinds of real experiences and skills — without any of the usual kind of equipment — and translate that to treating people who are up in space for six months?” Menon said. “As we get more people landing on the moon and staying on the moon, it’ll be harder to evacuate people. And Mars is next-level in not being able to evacuate folks and really needing to apply wilderness-based medicine.”

Menon’s love of space started young. He grew up in Minneapolis, the son of immigrants from Ukraine and India. He credits visits to the Science Museum of Minnesota for sparking his interest, specifically an Imax movie called “The Dream Is Alive.” The film focuses on the U.S. Space Shuttle program and highlights footage taken by crews in space. It showed training sessions and missions aboard the Discovery and the ill-fated Challenger, which would disintegrate shortly after liftoff in 1986. (The film was completed a number of months before the tragedy.)

Menon’s interest in space fed a broader interest in science. While in high school, he published research conducted at the Minnesota Zoo, which got him thinking about pursuing a Ph.D. and a research career. After arriving at Harvard, he settled into Wigglesworth Hall, spending his first year in a room once occupied by actor Tommy Lee Jones before moving with blockmates to Lowell House. He also became interested in neurobiology and conducted Huntington’s Disease research for two years in the MGH lab of Jang-Ho Cha, then a Harvard Medical School professor and today the global head of translational medicine at the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research in Cambridge.

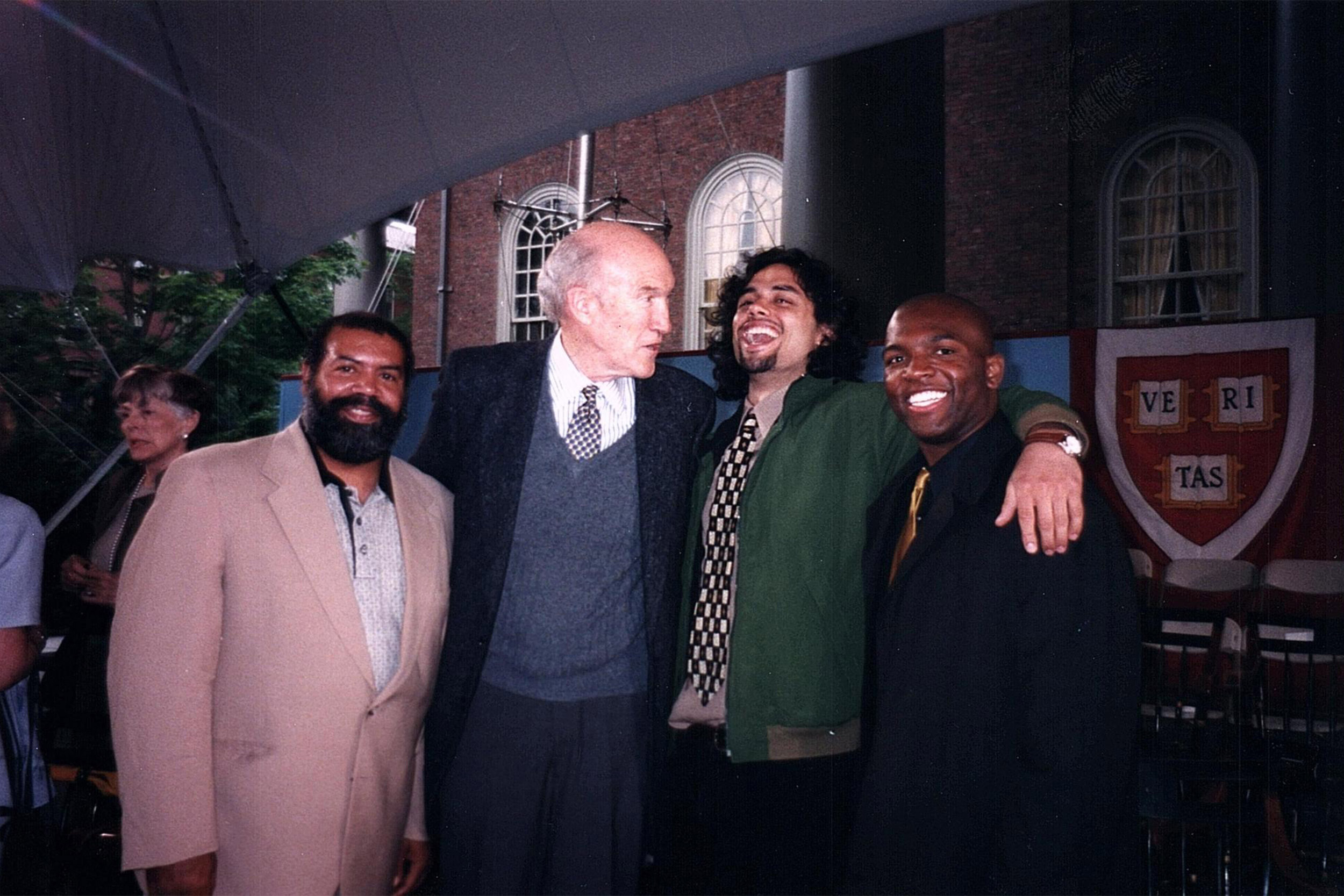

In 1997, Anil Menon participated in the Jumpstart program started at Harvard by undergraduate students. Menon’s stepfather, Martin Adams (from left), former Sen. Alan Simpson, Anil Menon, and Baratunde Thurston at Harvard’s 348th Commencement, June 10, 1999.

It was on a visit with Cha to see a Huntington’s patient that Menon began to consider a career in medicine.

“I really saw him help a patient directly with Huntington’s disease, and I got interested in having that hands-on, real-time, feedback and impact,” Menon said. “About my senior year I decided I wanted to go into medicine.”

Cha said Menon and a classmate worked at his lab at the same time, on transgenic mice that were models for the neurochemical changes Huntington’s causes in humans. He described Menon then as not only good at the science, but also friendly, fun-loving, and a good guy.

“They did some nice work,” said Cha, who has stayed in touch with Menon. Cha described an episode he said was typical for Menon. A former colleague contacted Cha because the colleague’s 6-year-old daughter loved space and asked whether Cha knew anyone at NASA. Menon was at SpaceX then and, when Cha reached out, sent the girl a video and SpaceX-related items.

Menon and his Lowell House blockmates became close friends who are not only still in touch, they helped get him into NASA, conducting mock interviews during the application process. Baratunde Thurston, who roomed with Menon his junior year, said Menon asked for help when he applied for this latest class, since it was his fifth attempt and he had been told the interview had been his weakness in prior rounds.

“A lot of us find our weaknesses and we avoid them — that’s a part of our body that we favor because it’s weak, or a part of our mind that we don’t exercise, because we don’t feel strong,” Thurston said. “And he was like, ‘I’m weak here so I need to work it out.’”

“I went to Antarctica and had to climb from low camp to high camp on Mount Vinson. I remember it being absolutely exhausting. It was just a 12-hour window, but I used all the skills that are helpful in these different team environments.”

Anil Menon

Thurston, a comedian and author of the 2012 New York Times bestseller “How to Be Black,” said they all jumped into the effort, including three former blockmates who had become attorneys.

“We grilled him. We became a NASA committee, and we did all kinds of Google space research,” Thurston said. “We’re like ‘Why do you think …?’ And ‘Why does your career path look like this?’ And ‘What would you do if …? And ‘Why would you leave SpaceX?’ He heard the feedback from previous attempts. So, he was arrogant enough to keep trying, but humble enough to take the feedback and try differently. It’s kind of a unique combination.”

Thurston said Menon was fun and really smart, even by Harvard standards.

“I remember hearing about how he showed up in organic chemistry — which is a class I didn’t ever take and would never take because I don’t believe in masochism — but he took that class, at least according to what is now probably legend, and he didn’t take notes,” Thurston said. “He just sat there and learned organic chemistry. With his mind. That was frustrating to hear.”

After Harvard, Menon went to Stanford, where he received a master’s degree in mechanical engineering in 2004, an M.D. in 2006, and did his emergency medicine residency and a wilderness medicine fellowship. While in residency, Menon joined the California Air National Guard and served in Afghanistan from June to August 2009 with the 129th Rescue Squadron. From there, his military and civilian careers ran in parallel. He worked in hospital emergency departments in California and Texas, and, in 2011 became a flight surgeon at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. In 2016, he became a lieutenant colonel with the 45th Operations Group at Patrick Air Force Base in Florida, responsible for human spaceflight support. In 2018, he became SpaceX’s medical director, building a 50-person medical team and developing a medical research program. He held that post until December, when he joined NASA’s astronaut program.

Menon’s drive to prepare for extremes extends beyond formal training to fitness. He participates in Ironman triathlons and an extreme fitness challenge called Kokoro — 50 hours of crossfit-type exercise. As part of his personal preparation for astronaut training, he and a friend scaled Mount Vinson, Antarctica’s tallest peak, in December. Testing himself physically, Menon said, is part of his preparation for challenges that he knows will test him in all sorts of ways.

“I see it as an accelerated crucible. They’re good because they’re short-lived and really challenging,” Menon said. “I went to Antarctica and had to climb from low camp to high camp on Mount Vinson. I remember it being absolutely exhausting. It was just a 12-hour window, but I used all the skills that are helpful in these different team environments, things like setting micro-goals, positive self-talk, breathing, focusing in the moment.”

Though Menon’s preparation has allowed him to perform when others might crumble, that doesn’t mean it’s been easy. One of his most difficult times came in Haiti while he was working at the main hospital in Port-au-Prince after the 2010 quake. The building itself was unsafe, so he and other physicians worked in a temporary field hospital set up outside. Buildings had collapsed across the city, over 100,000 had died, and the injured flowed in nonstop.

“I got used to a certain amount of injuries in the ER and found good coping strategies for that. But when I went to Haiti, it was truly overwhelming,” Menon said. “I remember this lady — a leg amputation from a falling building — it took her five days to come in. We were giving her fluids and blood and needed to get her to the OR. Her son was by me and asked how his mom was doing. I remember saying, ‘She’s OK,’ just trying to be positive. Then she passed away. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back for me, in terms of just seeing too much injury. I needed a moment to mourn the loss. Luckily, there were people who understood, who were supportive.”

Menon met his wife, Anna, recently named an astronaut for SpaceX’s Polaris program, during his first stint as a NASA flight surgeon. The pair continued to work together later, at SpaceX, and have two young children. In January, Menon and the others in the 10-person astronaut class reported to the Johnson Space Center in Houston for the start of two years of training, which runs the gamut from flying T38 jets to Russian-language training to operating space station systems, robotics, and spacewalks.

Though their dad is headed for a space adventure, Menon said his kids are most excited about something else.

“I promised to build a tree house in Houston,” Menon said. “I think that’s probably a lot bigger than the astronaut thing.”