Parachuting into a pandemic after historic spacewalk

Former Med School professor reflects on historic and jolting return to Earth’s new normal

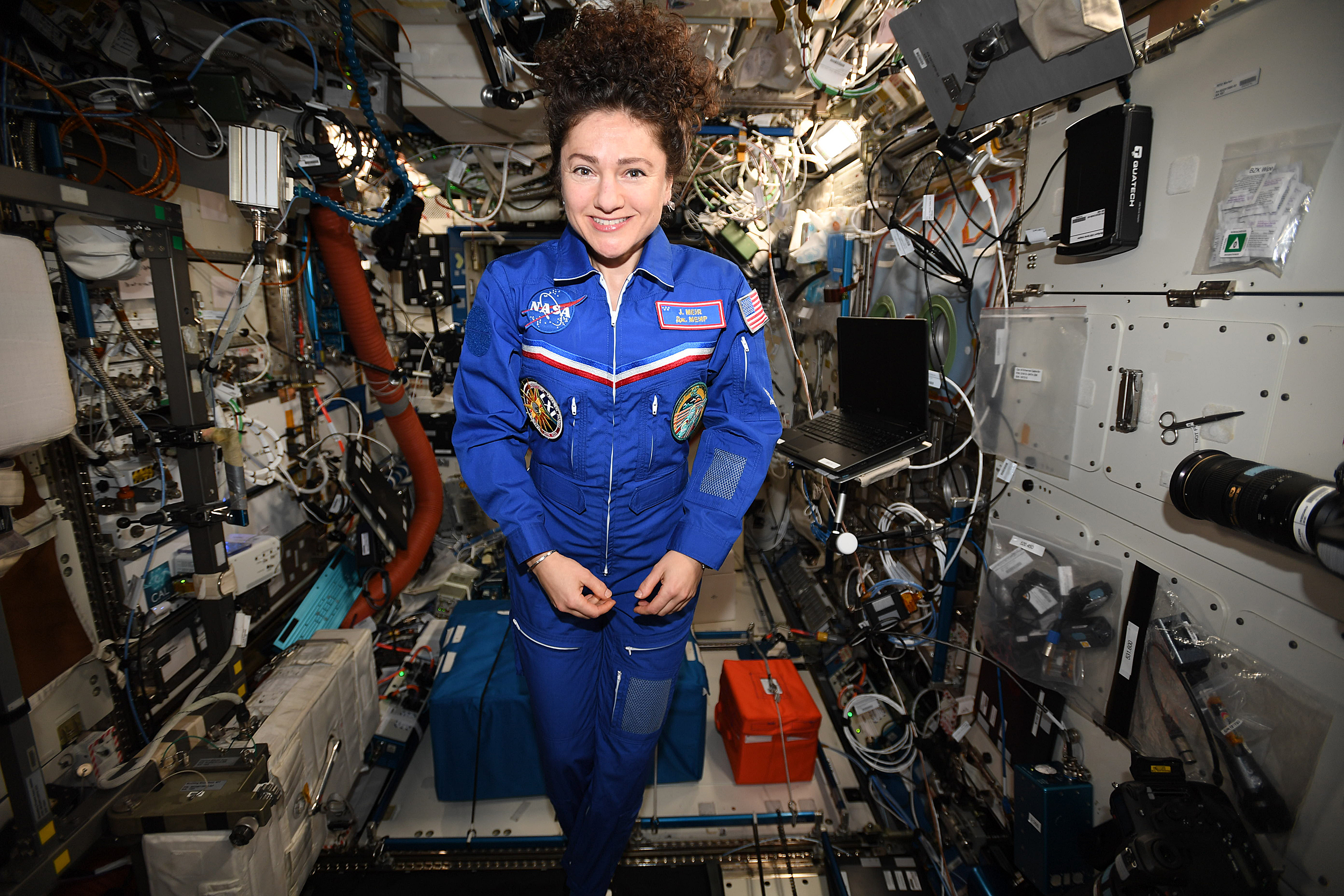

NASA astronaut Jessica Meir waves at the camera during a spacewalk with fellow NASA astronaut Christina Koch (out of frame). They ventured into the vacuum of space for seven hours and 17 minutes to swap a failed battery charge-discharge unit (BCDU) with a spare during the first all-woman spacewalk.

Images courtesy of NASA

Harvard Medical School Assistant Professor Jessica Meir was named to NASA’s astronaut class in 2013. A researcher in anesthesia at Massachusetts General Hospital, Meir, a scuba diver, a pilot, and an investigator into the effects of extreme environments on animal physiology, endured two years of training before getting into line for her turn in space. That came a year ago, in September 2019, when she rocketed to the International Space Station and weeks later rose to fame when she and Christina Koch made history’s first all-female spacewalk. Meir and two teammates lived in the space station for 205 days before literally parachuting into the middle of a pandemic, landing in Kazakhstan during COVID-19’s mid-April peak. Rounding out the year, in September 2020, Time named her among its 100 most influential people. Meir spoke to the Gazette about her tumultuous year in space and back.

Q&A

Jessica Meir

GAZETTE: How important was influencing people, being a role mode, among the reasons you became an astronaut?

MEIR: For me, it primarily was about science and the sense of exploration. But outreach has always been incredibly important to me and now as an astronaut, it is part of our mission statement at NASA. I’ve never really thought of it as being an influencer, but more in terms of giving back. I’ve thought about how I can promote science and give back to the communities and all the people who helped me along the way.

GAZETTE: When you look back at the college student you once were and the astronaut that you are now, are there specific lessons you could offer to young women who are interested in science?

MEIR: Looking back, I don’t think I realized how fortunate I was. Hearing other people’s stories and experiences, I never had moments in college or when I was younger of feeling like there was something I couldn’t do because of my gender or because of my background. I know that there are still many, many hurdles in terms of having true equity for women, for minorities. But I was very fortunate that I didn’t feel that struggle directly. My advice is to make sure you are doing what you are most passionate about, not what you think you should be doing or what your parents want you to do. If you’re not pursuing something you’re passionate about, you’re not going to excel at it, and you’re not going to be happy. Also be aware that you need to push yourself, go outside of your comfort zone. Without taking a little bit of risk and a little leap of faith, I don’t think you’ll be able to accomplish great things. You also should realize that it is OK — actually expected and necessary — to fail along the way. That’s true for me and all the other astronauts I know.

GAZETTE: You were on the space station for 205 days and came back during the height of our first wave of COVID. How were things different for you when you landed?

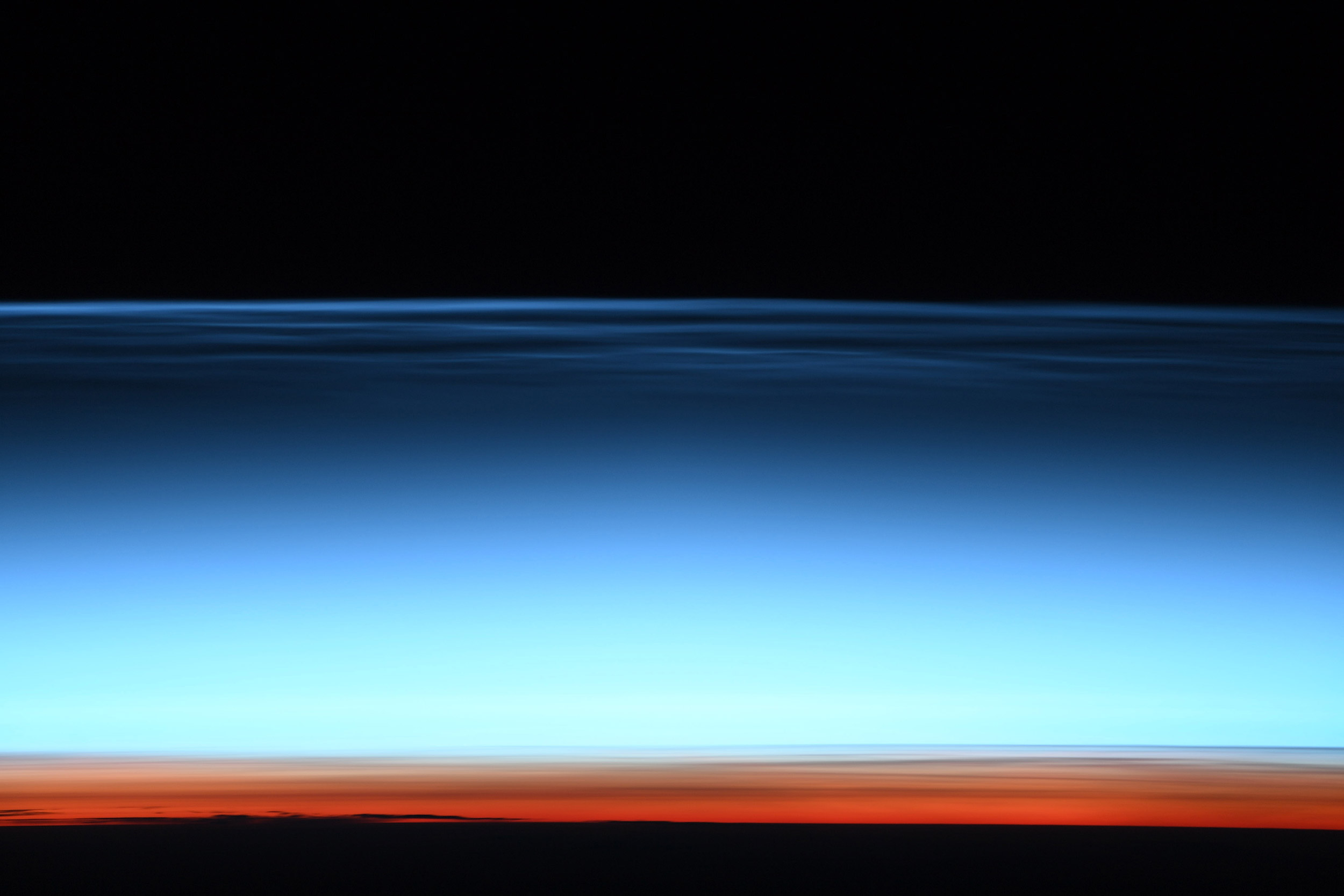

MEIR: When we launched in September there was no COVID and watching it unfold from up there was kind of surreal. We were very, very busy, and we weren’t able to deal with it, process it, as much just because we had to focus on the tasks at hand. But we were looking out the window at these extraordinary views of our planet, as beautiful as before COVID, and thinking about the magnitude and the scale of what was happening down there and how everybody’s lives were being affected, all 7.5 billion people, whether they were actually sick or if they just had their routines changed. We were thinking this is like a bad science-fiction movie, where there’s three humans on the space station during a global pandemic. All the people supporting us, of course, were affected, but NASA Johnson Space Center set up a secondary Mission Control Room that they would disinfect between shifts. The same people always worked in one room, and the other shift worked in the other room so they didn’t come in contact with each other. If we had not had those news sources and been talking to people, we wouldn’t have known what was happening. That’s a testament to the ground teams and how NASA always rises to whatever challenge comes our way. For the last 2½ months, it was only three of us up there: Drew Morgan, a medical doctor, and our Russian Commander Oleg Skripochka. Then we were joined by NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy and two other Russian cosmonauts for the last eight days of our mission. Chris talked about it a lot. He said, “You have to prepare for this. You’re going back to a different planet, and it is extreme.”

GAZETTE: Were you worried about your family?

MEIR: I was worried in the same way that everybody was, but nobody was in a dire medical situation. One of my sisters actually did have it, but it was so early on that it was before people realized that she and her husband had the stereotypical symptoms. They did end up testing positive for antibodies later, but they weren’t too sick. I was worried about my mom the most, given that she’s older. I’m actually only just getting to see my mom this week. I’ve been back for five months. As it has been for everybody else, just adapting to it and navigating through it has been hard. I actually got kind of depressed when I got back, not being able to see people and do anything. In the end, I was able to travel, see some family members, and spend a lot of time outside in nature. That cured me because that’s something that you can still do, and I have such a close connection to nature that that usually cures me anyway.

GAZETTE: Any lessons that you have gleaned while being confined in the space station for folks here who may be dealing with isolation from COVID?

MEIR: In space, isolation is just part of the mission. We expect that, and there’s a very good reason for it. And there are so many extraordinary things that we’re experiencing and doing that isolation isn’t a negative part of that experience. But here on Earth, our society is not built that way; we humans are not wired that way. I find it much more difficult to have this isolation on Earth. There are a lot of common strategies that we use as astronauts that people can benefit from down here. Part of that is sticking to a routine: still getting up and getting dressed and going through your day instead of just sitting home in your sweatpants all day. I don’t think that helps your mental attitude and your psyche. Then, making sure to make exercise part of that schedule. That’s so important for physical and mental health. And having good communication strategies with your loved ones and remembering the importance of interacting with people outside of your bubble.

GAZETTE: Do you still go into work every day now? I imagine being an astronaut isn’t something you can do via Zoom.

MEIR: How it works when we come back from a space station mission is that the first two months are very busy. From a physiological and medical standpoint, that’s when you’re the subject, and they collect lots of data right upon your return. We do a lot of debriefs to make sure that we give back whatever is fresh in our memory to help improve the program. The first week back we lived in quarantine at NASA, on site at the facility. They did an extended quarantine for us — given COVID — because the immune system is actually dysregulated in spaceflight. Psychologically, I wouldn’t say I was more stressed. I was probably less stressed in space, but whatever stress being in space has on your body, whether it’s the microgravity, the radiation, the different environment, those things seem to have an effect on the immune system that we’ve measured for decades now. After two months, we enter a four-month period that is a mix of doing PR and having time off to recoup. Then you go back into the office for your official ground job again. That time is coming up for me, so in the middle of October I’ll report to the office. I don’t know what my assignment is yet, but I’ll become a normal person in the office again, working the ground job and also maintaining proficiency training, with spacewalk training and flight training, until I’m assigned another mission in the future.

GAZETTE: Speaking of spacewalks, your historic spacewalk was a highlight of your time on the space station. What was that like? Can you describe stepping outside, what you saw and what you felt?

MEIR: It was absolutely incredible. Just being in space in general was so much more incredible than I ever imagined, which is saying a lot because I’ve thought about it since I was 5 and had been training for it for seven years. But there’s just something about floating all the time and looking back at the Earth and having that perspective that I cannot even put into words. It was even more extreme and overwhelming than I ever imagined. Doing a spacewalk is up one more level. You are out there in your spacesuit, your own little mini-spacecraft, completely dependent on it. Even the Earth looks a little bit different than it does through the windows of the space station when you’re looking at it through your thin visor. I think it literally looks different, but there’s also the realization that there’s just this visor and then the vastness, the void of space. On your first walk, you’re always the second person out of the hatch. Christina had done a spacewalk before, and she was already out there. It was daylight when I came out. I look down, and I see my boots, and then I see the Earth below. The sense of motion is stronger when you’re out for a spacewalk than it is looking through the window and you see how quickly Earth is moving beneath you. I didn’t know how it was going to feel. Some astronauts describe a feeling of falling — not everyone feels that way. Some people are terrified. They are able to get out there and get the job done, but sometimes they’re uncomfortable. But I didn’t really have a sense of fear. I was just in awe of the fact that this was actually happening, this dream was coming true.

Jessica Meir brought a Harvard flag along for the ride. The Expedition 62 crew poses for a portrait aboard the International Space Station’s U.S. Destiny laboratory module. Roscosmos Commander Oleg Skripochka (middle) is flanked by NASA Flight Engineers Andrew Morgan and Jessica Meir.

GAZETTE: What was your mission out there? Were you nervous at all about that?

MEIR: Your muscle memory kicks in because you’ve trained for so many hours and you know exactly how to operate the suit and how to use the tools. We have to be focused on what we’re doing, because spacewalks are the riskiest thing that we do and are the most challenging thing that we do mentally and physically. So you really have to just focus on your job. You’re not up there philosophizing. You go through the actions you’ve trained for on the ground. I tried to remind myself to steal a few moments to look at the Earth and appreciate that, to look down to Christina and see the Earth behind her and just try to sear this into my memory because it’s so extraordinary. We had to replace this box that had failed, the battery charge-discharge unit, which is an essential element of the power channel on the space station. We needed to replace that unit to bring this power channel back to life, and there’s only two other spares out there. If we damaged it or didn’t install it correctly, it would be quite a bad thing for the space station. So most the time you’re just thinking, “OK, don’t make a mistake. Don’t damage this hardware.” It’s all-consuming for sure.

GAZETTE: What about its significance as the first all-women spacewalk?

MEIR: Even though it was also historic, I had to be focused on the job. You need to make sure that you’re operating safely and that you can react to an emergent situation with your crew member, if necessary. I had also only been in space for two weeks so I was still figuring out how to float around and getting used to everything. The historical component of the spacewalk meant more to me after it was conducted, after we were back in the hatch safely, and we looked at each other and hugged, and we were really happy with how it went. But that’s not to take away from the significance. We felt so privileged to be a part of it, but it was more of a tribute to the generation of women and other minorities who didn’t have a seat at the table, who had to break those glass ceilings, and that pushed to get us where we are today. We are the result of their work and the fact that we had this opportunity is a result of all of that work. We were really representing those generations, and that’s most important to me. Obviously, we have a way to go in terms of social equity in this country, but I hope that this did show that we’re moving in the right direction.

GAZETTE: Other than the walk itself, what was the main work there like? Was it conducting experiments the whole time? Were there maintenance tasks?

MEIR: A blend of all those things. Our primary purpose is science but from a realistic point of view we’re not up there doing science all day long. The space station is over 20 years old, so things break, and we have to fix them. We have to maintain things to keep them functioning. So, one day we might be fixing the toilet all day — the toilet happens to break a lot while you’re up there. It was very rewarding for me as a scientist to be conducting the scientific experiments. They ranged from physiology and medicine to combustion science — even flames burn differently in space without convection. We do protein crystal growth experiments — you can grow larger and more pure proteins, which has had a lot of implications for the pharmaceutical world. There are even drugs in clinical trials right now based on those space station experiments. There’s one for Duchenne muscular dystrophy in clinical trials.

GAZETTE: Was there an experiment thought particularly interesting?

MEIR: We were working with what are called “mighty mice.” Myostatin is the inhibitor to muscle growth, part of our normal physiology, but in certain bone and muscle degenerative states, this pathway plays a really important role. We had mice that were myostatin knockouts and others that we were giving therapeutic doses that were disrupting that pathway. These mighty mice had much larger muscle mass, and they were able to maintain that muscle mass in space, despite the microgravity, and also maintain their bone density. That is interesting in its implications for long-duration space travel for humans. We exercise for 2½ hours a day, and we have to lift weights. We need that resistance, that loading to keep our bones and muscles healthy. But on long duration missions to Mars, for example, the machines that we’ve built in the space station are too big to have their equivalent in a small spacecraft. So we need to come up with either some small piece of equipment that still accomplishes all of that or some other therapeutic strategy. There’s also a possible benefit back on Earth. There are a lot of disease states — osteoporosis and other bone and muscle degenerative states — that could benefit from some kind of therapeutic. So it’s really exciting work.

GAZETTE: Are you definitely going to go back into space?

MEIR: I hope so, but we never know for sure. Assuming everything goes well during your mission, which it did for me, and you’re still medically qualified, then you get back in line for another mission. You’re not even medically certified again until six months after you land and for me, that’ll be in October. I would love to be part of those Artemis missions and go to the moon, but I’ll have to wait and see how that plays out. Right now, we’re in an incredibly exciting time because we’re developing new vehicles. We have SpaceX with their successful test flight so we’re launching from the U.S. again — and hopefully with Boeing too down the line. Then, with Artemis, we’re getting ready to send the first woman and the next man to the moon. We have the Orion spacecraft being built to make these missions beyond low Earth orbit, to go back to the moon, to go on to Mars. And the Space Launch System, the rocket that will enable that, is currently being built by NASA. So we’re at this precipice where lots of different things are happening.

Interview was lightly edited for clarity and length.