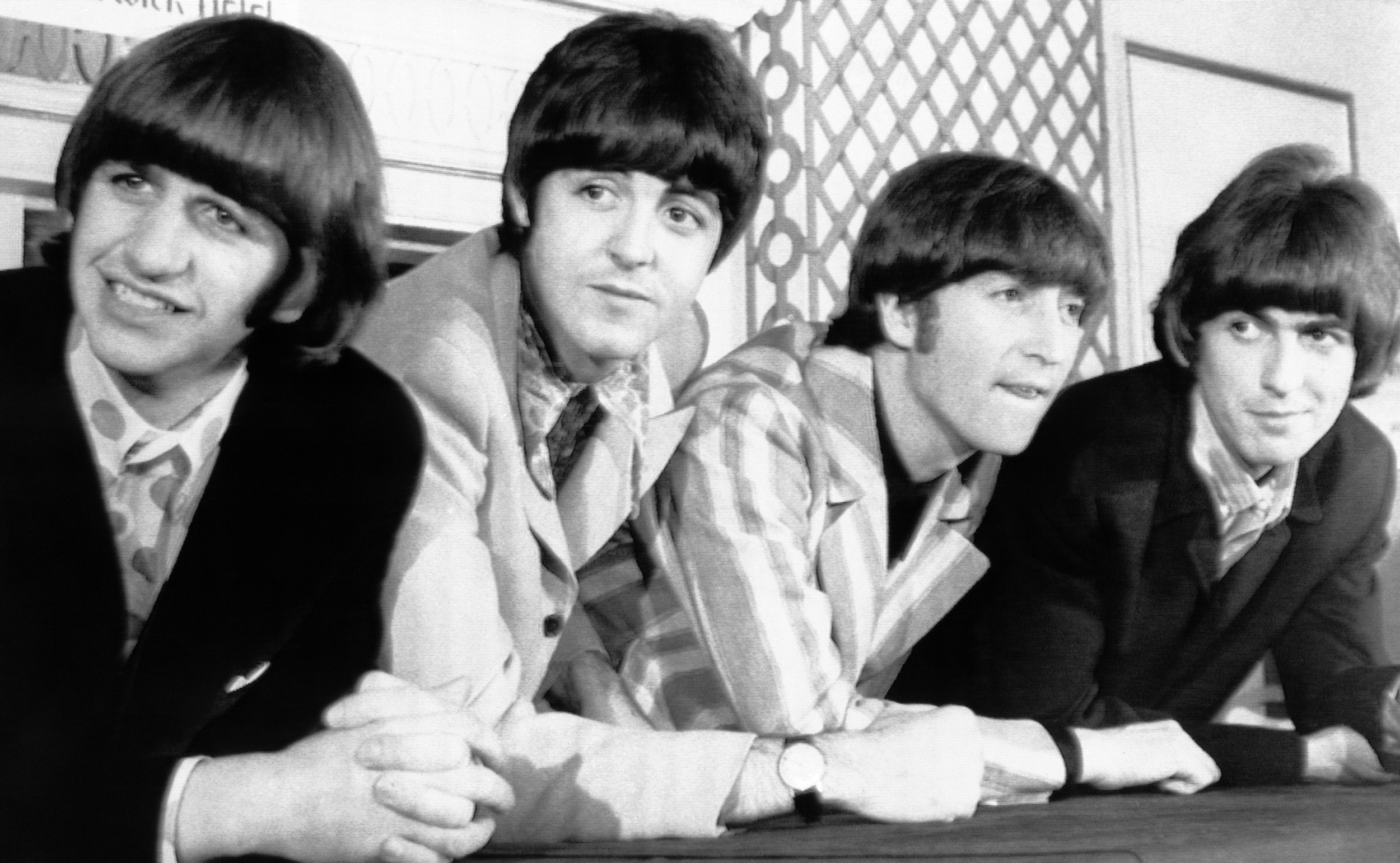

The Beatles in 1966.

AP file photo

Why do some bands rocket when others sputter out?

Don’t discount influence of serendipity in success of Beatles, other artists, Cass Sunstein says

Why do some bands catch fire while others don’t? Is it a matter of talent? Or are there other factors? Take the Beatles: If they suddenly appeared for the first time on TikTok now, would their exceptional talent be as apparent and embraced as it was in the early 1960s? Would they have evolved creatively to become a revolutionary musical force if they had not first found enormous pop chart fame? Maybe, said Cass R. Sunstein ’75, J.D. ’78, the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard, and longtime Beatles fan. Writing for The Journal of Beatles Studies, a new academic publication from the University of Liverpool that will debut in September, he argues that as great as they were, the early Beatles needed some “serendipity” to break through. The Gazette spoke with Sunstein, founder and director of the Program on Behavioral Economics and Public Policy at Harvard Law School, about the recipe for superstardom. Interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Cass R. Sunstein

GAZETTE: Tell me about your interest in the Beatles.

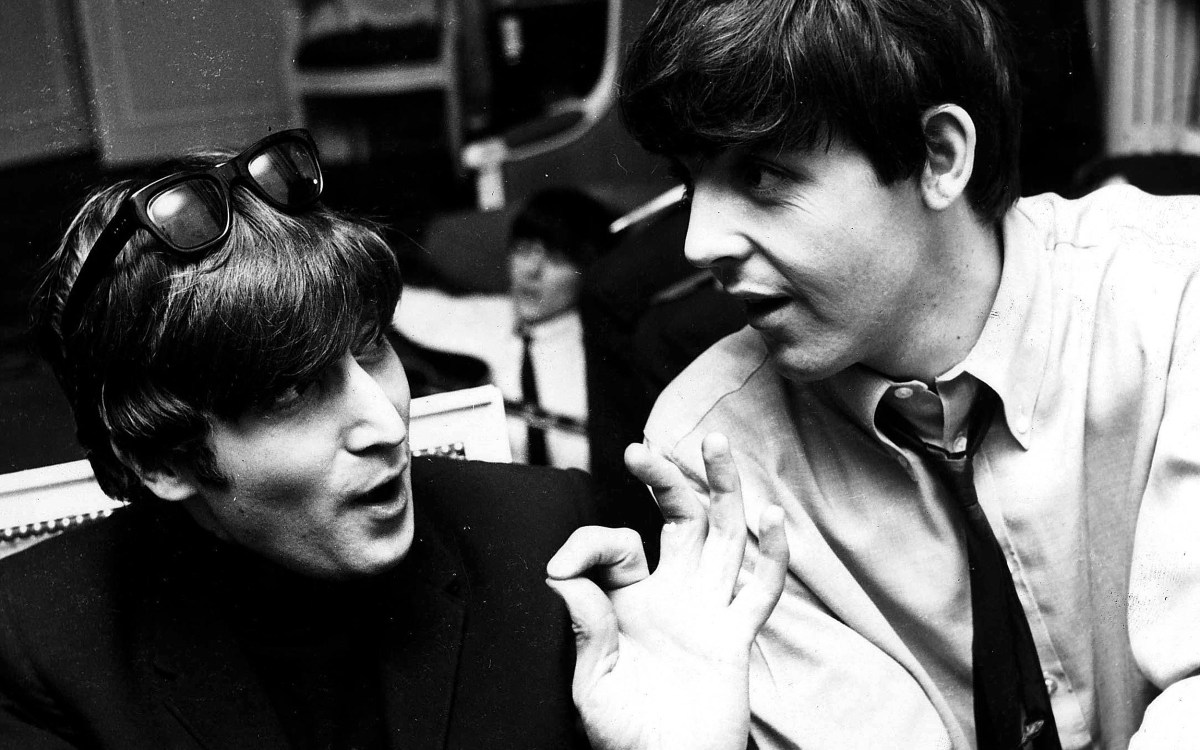

SUNSTEIN: I’ve liked the Beatles for a long time — very much. As much as I’ve always liked and loved them, I’d say my amazement at the Beatles has grown over the last 10 years. The amazingness of their songs — John Lennon and Paul McCartney are both out-of-this-world extraordinary and so different. Ringo is as terrific a rock drummer as there could be for that group. George is extraordinary, too. That these four guys from Liverpool could be who they were is magical, and that Lennon and McCartney met each other in their teens and turned out to be genuinely geniuses — that’s magical.

GAZETTE: You examine the “Fab Four” era of the Beatles to explore the mystery of why some artists become hugely popular while others don’t. Quality is often a reason, but not always. What are some determinative factors, and why is it so hard to predict?

SUNSTEIN: Whether we’re talking about musicians or poets or novelists or actors, the people who really make it might not be better than the people who don’t. What gets the people who make it to make it is often captured by the word “serendipity,” which is a placeholder for such things as who is enthusiastic about what song or what poem at what point in time; whether seven people or 80 people or 8,000 people get excited when that excitement turns out to launch the person; whether the person gets access to economic backing, perhaps because someone happens to read a poem or read a novel or hear a song who thinks “that one’s extraordinary” rather than another one that was also extraordinary that they didn’t read or hear. That role of early enthusiasm, influential enthusiasm, a single sponsor, a group of fans, or just a night when everything goes really well, that is what’s neglected.

Now, let’s think of the Beatles: After they were turned down by a bunch of studios, they almost gave up; the very person who was famously their great producer, George Martin, didn’t think much of them and had to be persuaded to release singles by them. “Love Me Do,” which was their first hit, the studio had no big hope for. It turned out that it did well for reasons that were not related fully to its quality. These and other things probably lost to history could have gone the other way, and who knows?

If it seems a little provocative to suggest that the Beatles could have failed, well, John Keats died thinking he was pretty much a loser and a failure. “Harry Potter” was turned down by multiple publishers. Jane Austen was not thought to be the best of the novelists of her time. William Blake was essentially unknown. Just like the fact that Taylor Swift becomes who she is and (I’m going to make up a name) Mary Johnson gave up at the age of 19. That might not be because Taylor Swift is better than Mary Johnson. I’m a huge fan of Taylor Swift, I should say. I think she’s phenomenal, so this is not a knock on her, and I’d be amazed if there’s a Mary Johnson who’s as good who gave up. But I probably shouldn’t be amazed. There probably is a Mary Johnson who’s maybe as good or good in a different way who gave up. This is about success and failure generally.

GAZETTE: Does the enduring popularity of the Beatles demonstrate that their extraordinary talent was perhaps more influential to their success than the early serendipitous factors?

SUNSTEIN: That’s a counterargument to the thesis I explore, which is that the Beatles could have disappeared. According to that thesis, they were both amazing and fortunate, and it was social influences and serendipity that helped them become the Beatles. The counterargument would be to look at their constant rise to popularity, where lightning didn’t just strike once, it struck many times over the years, with new generations discovering them. You could say that’s testimony to their extraordinariness, which could support the implicit thesis of the movie “Yesterday” — that if people heard the Beatles now, they’d go crazy with enthusiasm. Maybe. If my thesis is that, in their era, they could have fallen apart if they hadn’t gotten fortunate at a key time, then that’s consistent with the view they were excellent then and became even more amazing over the years they were together. But you could still say they needed that stroke of serendipity at the time when they were extremely vulnerable.

It was probably multiple things. They needed manager Brian Epstein to go crazy for them. They needed him to be who he was; they needed George Martin to be convinced by people at the record label; they needed George Martin himself to give the nod; they needed Liverpool to have a kind of cascade of support. So, they needed a lot of stuff.

What I don’t know is whether the fact that they get rediscovered is really independent rediscovery. You’re not just discovering some obscure group. You’re rediscovering the Beatles. And the Beatles are iconic. So, the fact that people discover them and love them isn’t independent. It’s tainted in the sense that it’s not uninfluenced by the fact that they are the Beatles.

“Are there other people who — if they had a couple of years to be inventive — could have done a ‘Revolver’ or ‘Rubber Soul’? Every bone in my body cries out, ‘No!’ But my brain whispers, ‘Maybe.’“

GAZETTE: For those who are not exceptionally good or terrible, research shows that a band’s popularity can be directly influenced by social factors mostly unrelated to its musical quality. What are some of those influences?

SUNSTEIN: Bob Dylan, who I confess is one of my very favorites, he was part of a folk music scene, a group of singers in Greenwich Village who basically didn’t do albums. A guy named Robert Shelton wrote a story in The New York Times on Sept. 29, 1961, that said, “20-Year-Old Singer Is Bright New Face at Gerde’s Club.” That rave review vaulted Dylan to a different league and helped him get a record deal, which was extremely unusual among his crowd.

What would have happened to Bob Dylan without Robert Shelton? Not at all clear. So that’s one kind of social influence. It might be an appearance — it could be some television program; it could be the Grammys. It could be that someone gives them an opportunity. Let’s say there’s a band or person who’s super popular and great and says, “Here’s the next big person” and they open for them. That could turn into something great. Taylor Swift, I know because I was at a concert of hers, the people who opened for her then were Haim. She also helped Vance Joy, a guy from Australia who is amazing. Ed Sheeran was another. You open for Taylor Swift, and something great can come for you. That’s another example.

GAZETTE: After considering other possibilities, you conclude “with trepidation” that the Beatles likely would have succeeded even without Beatlemania because of their extraordinary talent, but you said we can never be certain. Why not?

SUNSTEIN: Basically, the answer to your question is that history is run only once, so we don’t know. This is extremely intriguing and not knowable. The Beatles, at the time they first became the famous Beatles, were very, very good. Were they really Beatles-level good? No, they weren’t. Think of their early songs. “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” is very good. “She Loves You” was really good, and “Love Me Do” is really good.

Are they a lot better than the other groups at that time? If you listen to Dave Clark Five — the insufficiently beloved Dave Clark Five — I like them. Listen to “Glad All Over” or “Catch Me If You Can.” They had about seven really good songs, in my view. Were they significantly less good than the Beatles at that time? I think so, but I’m not sure.

The Beatles became the Beatles only after they were sensationally popular. Lennon and McCartney were freed to go in a lot of amazing directions. My favorite Beatles album — I think it’s their best— is “Revolver.” They were able to be more inventive. Are there other people who — if they had a couple of years to be inventive — could have done a “Revolver” or “Rubber Soul”? Every bone in my body cries out, “No!” But my brain whispers, “Maybe.”