Alison Bechdel needs to know what happens next

Author explains time-sensitive process behind acclaimed graphic memoirs

Illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

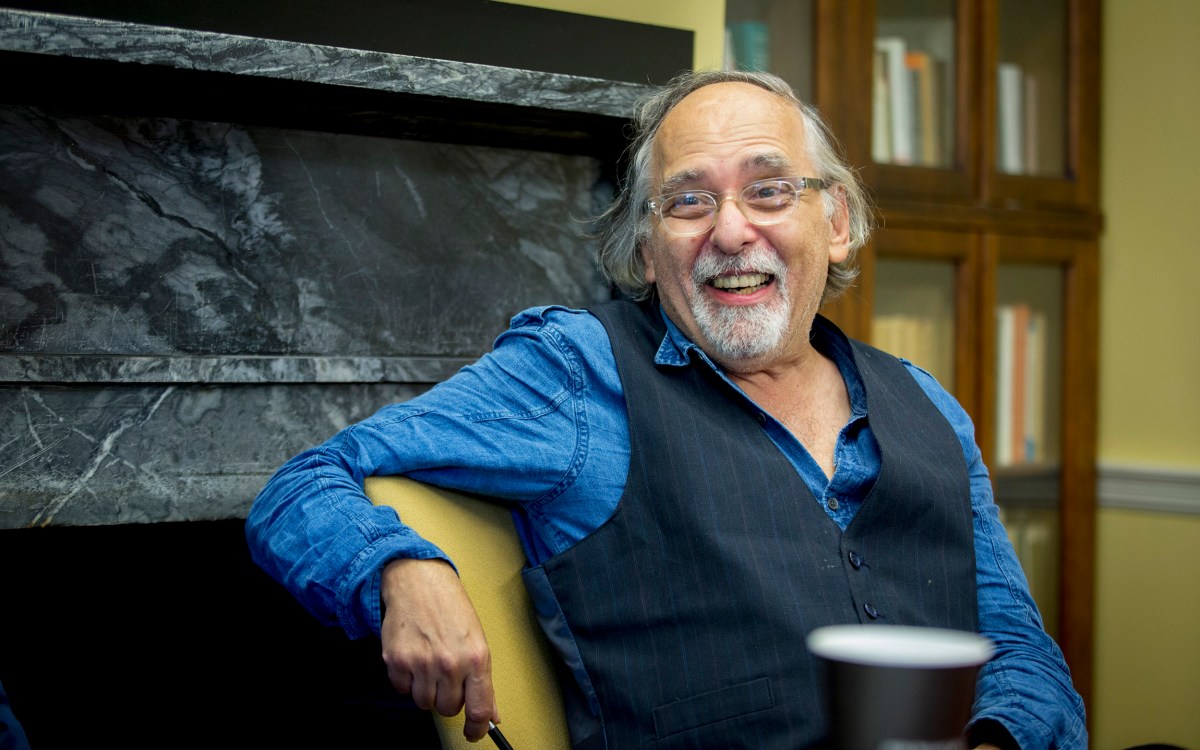

The cartoonist, memoirist, and MacArthur “genius” Alison Bechdel described the myriad ways she has wrestled with time during the 2022 Rita E. Hauser Forum for the Arts on Tuesday.

“The main thing I love about memoirs is the challenge of finding a coherent story in the random events of life,” said Bechdel, who published “The Secret to Superhuman Strength,” a book about her relationship to exercise, last May. “You can’t make anything up. So much of writing for me is … figuring out how to sequence things, how to figure out what comes next in the story or argument. And I find that it’s only by engaging in that process that I learn what the story’s about or what I’m trying to say.”

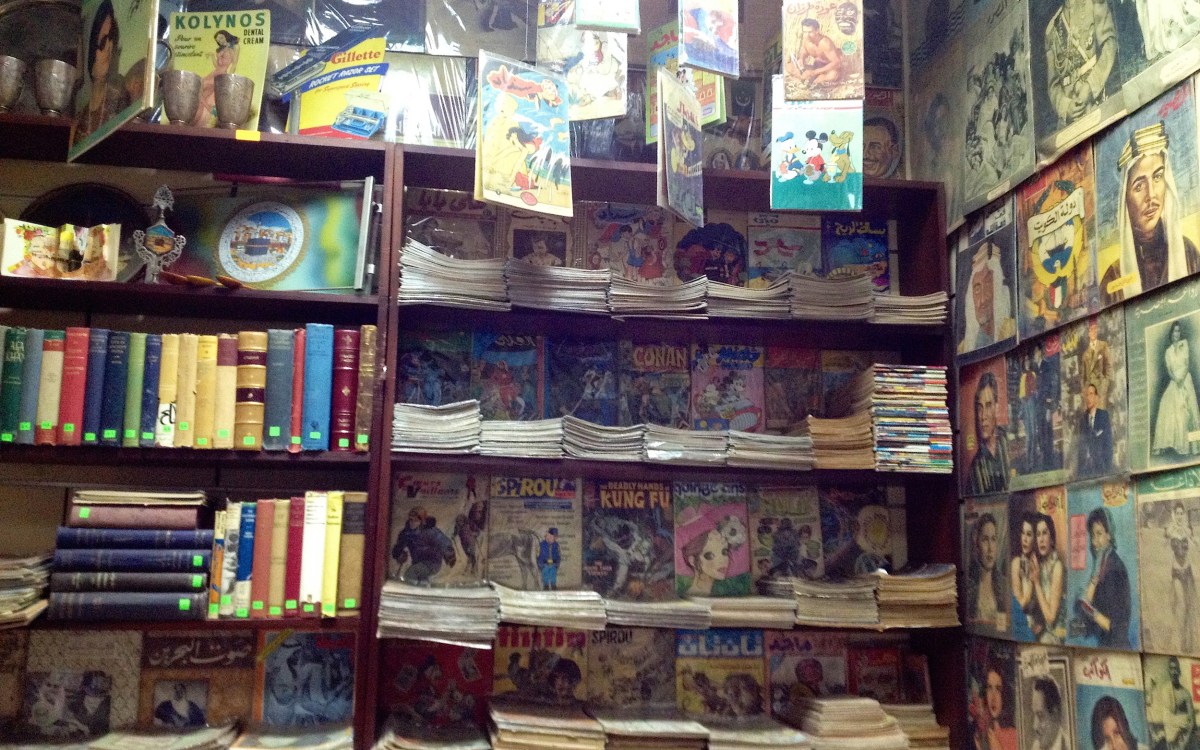

In her talk, titled “The Psychochronology of Everyday Life: Time In Graphic Memoir,” Bechdel explained how childhood diaries and old family photos served as source material for the larger stories she wanted to tell about generational divides and filial relationships in her first two memoirs, “Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic” and “Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama.” “Fun Home” examined Bechdel’s relationship with her father, an English teacher and funeral home owner who came out as gay when Bechdel was in college and died soon after in what his daughter suspects was a suicide. The book was later adapted into a musical and received five Tony awards.

“Are You My Mother?” focused on her mother’s unrealized artistic ambitions and how they affected their relationship. Bechdel recalled noticing in the contrast between photos of her mother as a young woman and in her 40s that something “had been extinguished from her eyes” as an older person. “That was the story” that she followed to structure the book, she said.

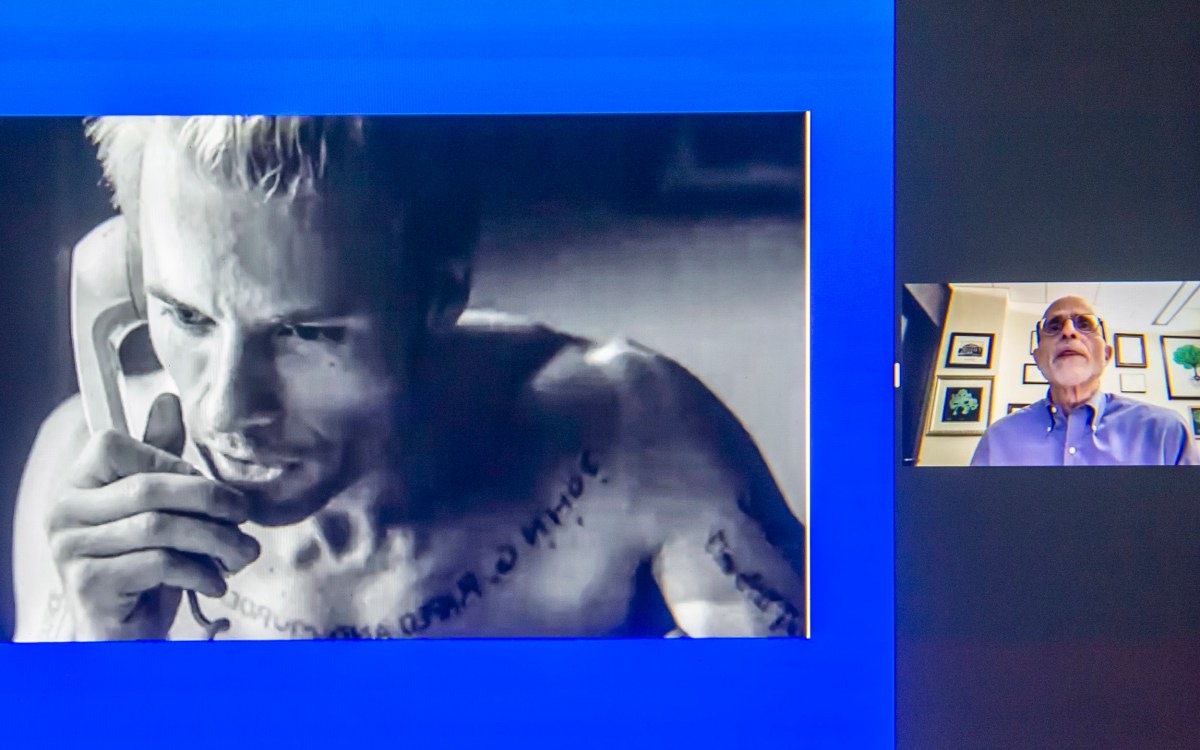

“It’s a neurological fact that every time you remember something, you degrade it a little bit in your circuitry,” said cartoonist and memoirist Alison Bechdel in a virtual talk. “So all my once-pristine memories of my father will become layered over with what I’ve written … I kind of lost my originals.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

After a long break from keeping a regular diary, Bechdel developed a new kind of creative practice while writing “The Secret to Superhuman Strength.” Feeling stuck, she used a brush to draw one vignette every day as a way to get into her body and out of her head.

“Using a brush instead of a pen was a way of getting outside of my comfort zone, because there is no sketching or reworking,” she said. “In a way it’s still me obsessively keeping track of myself in this kind of compulsive way I used to do. … But it feels very different. My mind and my body are working together.”

After her presentation, Bechdel spoke with Hillary Chute, an English professor at Northeastern and a comics and graphic novels columnist for The New York Times Book Review. Chute asked Bechdel about her use of literary and historical figures as characters in her books, including James Joyce, the 19th century English Lake Poets group, and the 20th-century psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, famous for his work on play and childhood.

“I’m getting something from these people, trying to know what they know, trying to link my experience to theirs,” said Bechdel. “I’m just alone in my basement 24 hours a day, so to be able to touch Margaret Fuller, and climb a mountain with Jack Kerouac — that’s great.”

A College student writing an essay on “Fun Home” submitted a question for Bechdel about how nostalgia influenced her narratives.

“Nostalgia comes so easily, especially when looking at family photographs, because all the pain and the Sturm und Drang is over,” said Bechdel. “I’m always trying to be honest, and see clearly, and not trying to imbue what I’m doing with anything except what is actually there, which is what any good writer would do.”

Another audience member asked if Bechdel’s rituals of documentation had affected her memory.

“They have definitely eroded it,” she answered. “It’s a neurological fact that every time you remember something, you degrade it a little bit in your circuitry. So all my once-pristine memories of my father will become layered over with what I’ve written, what I’ve seen in the musical version of ‘Fun Home,’ things people have written about it. I kind of lost my originals. But I guess that’s just a trade-off that I’m willing to make.”