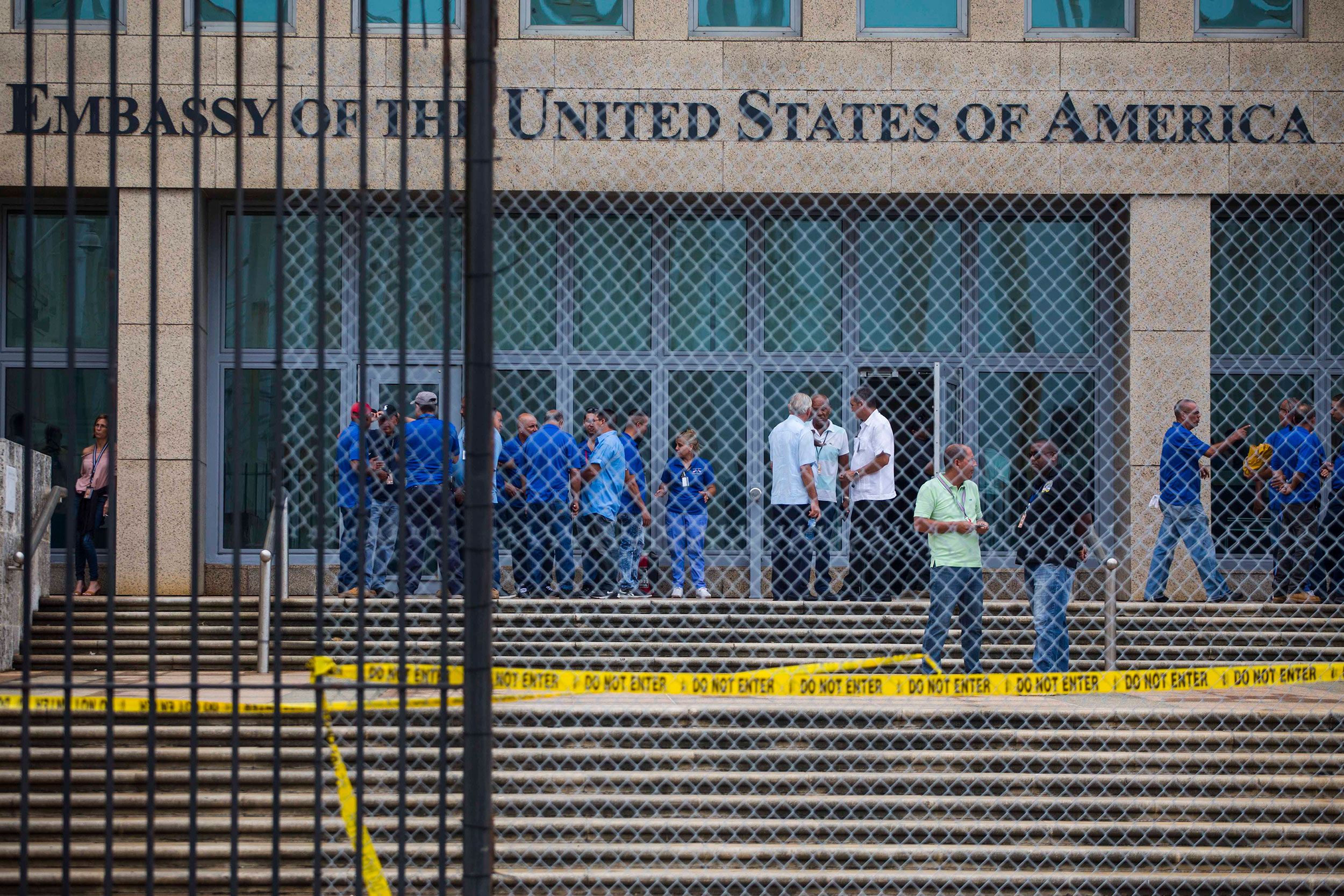

In September 2017, following months of mysterious health ailments at the U.S. Embassy in Havana, more than half of the U.S. diplomatic corps was ordered home. A recent flurry of cases overseas has created new concerns.

AP File Photo/Desmond Boylan

Rush to stop ‘Havana syndrome’

But cause, suspects unclear as scores of U.S. spies, diplomats, security staff hit by mysterious neurological injuries overseas

In 2016, dozens of diplomatic staff at the U.S. and Canadian embassies in Havana began experiencing a sudden onset of health troubles with no apparent cause. They reported a variety of symptoms, including vertigo, nausea, vision and hearing difficulties, memory loss, and headaches. Many said they felt something pressing or vibrating around them or heard noises just before the symptoms appeared, leading some to suspect they had been exposed to a high-intensity burst of energy or sound waves.

Known as Havana syndrome, today there are at least 200 CIA, State Department, and Pentagon personnel stationed overseas who have been affected. (President Biden signed a bill on Friday providing financial help to victims.) Intelligence agencies have been unable to determine what’s behind the incidents, although some officials believe they are the result of attacks by a U.S. adversary. Now, a recent flurry of high-ranking U.S. diplomats, spies, and security aides have been treated for Havana syndrome, possibly signaling an escalation of some sort, intelligence analysts say.

“Perhaps this is a message sent — that nobody is immune to this,” said former CIA senior operations officer Marc Polymeropoulos during a recent Harvard Kennedy School talk with Paul Kolbe, director of the Belfer Center’s Intelligence Project, and Adam Entous, staff writer at The New Yorker, who started reporting on the topic in 2018.

The most recent victims include a U.S. diplomat in Serbia who was evacuated by the CIA last month, according to a Wall Street Journal report, and an aide traveling with CIA Director William Burns in India who developed symptoms. In August, Vice President Kamala Harris’ trip to Vietnam was delayed after two officials at the U.S. embassy in Hanoi became ill. The CIA replaced its Vienna station chief for failing to adequately respond to reports of Havana syndrome-like symptoms by two dozen intelligence officers and diplomats this summer. Police in Vienna are investigating the incidents.

“I lost my long-distance vision. I couldn’t drive. I could barely go to work,” said Marc Polymeropoulos, who experienced Havana syndrome firsthand. Polymeropoulos (clockwise from left), Paul Kolbe, and Adam Entous discussed who might be behind what they see as a national security threat.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The cause of these illnesses has not been identified, but one theory is high-intensity microwaves may be to blame. Russia has a well-documented history dating back to Josef Stalin of using microwaves against the U.S. to disrupt intelligence operations. An assessment of Havana embassy victims by the National Academies of Science in 2020 said “directed, pulsed Radio Frequency energy” was the “most plausible” primary source of those injuries. Private companies sell weapons systems that use directed energy to knock out drones.

“This is not newfound technology,” said Polymeropoulos, a 26-year counterterrorism specialist who believes he was attacked during a trip to Russia in late 2017. “I think we know what it is.”

As the CIA’s deputy chief of operations for Europe and Eurasia, he went to Moscow to meet with the U.S. ambassador and embassy officials, as well as his counterparts in Russian security services. Though the Russians were “not thrilled” to see him and he was surveilled and hassled by authorities, there had been nothing alarming about the trip to that point, said Polymeropoulos.

Then one night, he woke up in his hotel room with vertigo-like symptoms.

“The room was spinning. I had a blinding headache; I had ringing in my ears; I felt like I was going to be physically sick,” said Polymeropoulos. “This was pretty alarming and frankly, a scary incident, because I’d lost control.”

Back in the U.S., he sought help for what he first thought were lingering effects of severe food poisoning. From neurologists to infectious disease specialists, none were able to offer a conclusive diagnosis, and his health grew worse throughout 2018.

“I lost my long-distance vision. I couldn’t drive. I could barely go to work. I was pretty incapacitated,” he said.

Victims say the U.S. government, which calls Havana syndrome a “possible anomalous health incident,” has been slow to see a connection between those affected, to label the incidents as attacks, or to even acknowledge victims suffered from a physical illness.

A 2018 FBI report on the Havana embassy victims declared their conditions psychologically-driven, most likely due to stress. That “undermined” the efforts of those stricken, including Polymeropoulos, to get U.S. intelligence to take seriously Havana syndrome and the national security threat it posed, said Entous.

Still experiencing debilitating symptoms with no relief in sight, Polymeropoulos retired in 2019. Frustrated by the CIA’s inaction, he took his story public last year. In January he was admitted to the traumatic brain injury program at Walter Reed National Intrepid Center of Excellence, where he was diagnosed with occipital neuralgia. Traumatic brain injury is now the most common diagnosis, said Polymeropoulos, who has spoken to many other victims.

‘Largely guessing’

Though President Donald Trump publicly accused Cuba, “the suspicion right from the very beginning of the Trump administration … was that the Russians or the Chinese were responsible,” said Entous. “And that was based on who’s got the technological capabilities, who’s got the ability to project force in these parts of the world.”

Some Obama officials also believed Russia could be to blame. The Russians were very unhappy about the U.S. role in the Maidan Revolution in 2014 and other efforts to pull Ukraine closer to Europe. They also may have gotten wind of secret diplomatic talks between the U.S. and Cuba that had begun in spring 2013 and progressed well into 2014. President Barack Obama’s speech during his historic visit to Cuba in March 2016 had been well received, perhaps further irritating the Russians, said Entous.

But no one knew for sure.

“American officials were largely guessing,” said Entous. “I remember John Bolton, the national security adviser, was split 50/50 between China and Russia being the most likely culprit. When it happened in China [April 2018], he decided it must be Russia because he doubted the Chinese would do it in their own backyard. So that gives you a sense of the grasping-at-straws nature of this, rather than these assessments being based on concrete intelligence.”

Though not enough to establish “high confidence,” there is circumstantial evidence that points to Russia. U.S. intelligence has cellphone data of Russian military intelligence officers who were in the vicinity of Americans at the same time they fell victim to Havana syndrome. Many of the officers have been part of other Russian operations, said Polymeropoulos.

The attacks fit the Russian government’s penchant for outlandish acts of aggression on foreign soil, including the 2006 poisoning in London of Alexander Litvinenko, a former Russian Federal Security Service officer, with a radioactive isotope; the 2018 attack on former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter in England with a military nerve agent; and the 2019 shooting death of a Chechen separatist at a Berlin park in broad daylight, said Kolbe.

And the elements of the attacks fit “all the parameters” of hybrid warfare — “profoundly asymmetric,” not attributable or very hard to trace, extremely disruptive, and deniable, he added.

It’s a combat style the Russians, among others, favor.

A suite of measures

The quickening tempo of attacks and close proximity to Harris and Burns has escalated the sense of urgency in intelligence circles to positively identify the perpetrator and formulate an effective U.S. response.

“This has been an ongoing source of tension within the intelligence community, our reluctance to respond to these provocations as they’re happening,” said Entous. During the final days of the Trump administration, some ideas for how to respond were discussed by Pentagon officials but they “didn’t go anywhere” because many thought Russia was merely doing it as a “provocation,” he said.

Now that Burns has put counterterrorism experts out front, Polymeropoulos said he’s “confident” we’ll find out “soon” who is behind the attacks.

“There’s going to be a lot of pressure to take some relatively severe action,” perhaps even “a suite of measures,” he said.

But whether the U.S. will finally respond consequentially remains an open question.

“Are we going to be able to do enough to … ‘detect, disrupt, deter’? That’s sacrosanct language in the counterterrorism community,” he said. “Those policy recommendations are what we’re all going to be looking at, because that is how this is going to be stopped.”