Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker laments the rise of quackery in “Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters.”

Roy Scott/Ikon Images

Enough with the quackery, Pinker says

Harvard psychologist appeals to our rational faculties in new book

At a time when belief in science appears to be waning, conspiracy theories seem to be on the rise, and many Americans cannot agree on basic facts, Steven Pinker argues for a return to rational thought and public discourse in his latest book, “Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters.” Pinker, Harvard’s Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology, and author of “The Better Angels of Our Nature,” and “Enlightenment Now,” thinks “we will always need to push back against our own irrationality,” and that education, democracy, science, and journalism, along with an awareness of our own biases, can help us embrace a more rational approach to everyday issues. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Steven Pinker

GAZETTE: Can you define rationality in a sentence?

PINKER: I define it as the use of knowledge to attain a goal, where “knowledge,” according to the standard philosopher’s definition, is “justified true belief.”

GAZETTE: We see examples of seemingly irrational beliefs and behaviors every day, but you argue that people are fully capable of being rational. How do you explain that disconnect?

PINKER: First, rationality is always in pursuit of a goal. Sometimes that goal is rational for each of us as individuals but irrational for us as a society — a tragedy of the rationality commons, as when it makes sense for every shepherd to graze his sheep on the town commons, but when everyone does it, the commons gets denuded and they’re all worse off. In this case, if everyone is ingenious in gaining prestige within their political sect by glorifying its sacred beliefs and demonizing rival sects, that may work to everyone’s individual advantage, but not to the advantage of the whole society in its interest in the truth and the best policies.

Another part of the answer is that we are born with primitive intuitions that served us well in traditional societies but have become obsolete in a scientifically sophisticated one. For example, we have the intuition that living things harbor an essence, an inner stuff that makes them function and gives them their powers, and that disease comes from external contaminants that pollute it. That leads us to quack remedies like bloodletting, purging, cupping, and homeopathy, and opposition to genetically modified foods. Likewise, the intuition of dualism, that people have minds as well as bodies, leads naturally to a belief in minds without bodies, so we have ghosts and ESP and communicating with the dead. The intuition of design in our plans and artifacts leads to creationism and the superstition that “everything happens for a reason.”

Now most of us unlearn these intuitions when we buy into the consensus of the scientific establishment — it’s not as if we understand the physiology or neuroscience or cosmology ourselves. But many people don’t trust the scientific establishment, so they fall back on those intuitions.

Finally, the conviction that all our beliefs should be grounded in evidence is psychologically unnatural. I quote Bertrand Russell, “It’s undesirable to believe a proposition when there’s no ground whatsoever for supposing it is true.” But that’s not a truism: it’s a radical manifesto. Most of us insist on reality when it comes to our immediate surroundings and our everyday lives. We have no choice: It’s the only way to get the kids clothed and fed, to keep gas in the car and food in the fridge. But we may not care about literal factuality when it comes to distant and cosmic questions like: How did life arise? What happens in remote halls of power? What’s the ultimate cause of disease? Until there was modern science and record-keeping and journalism, we had no way of finding out the answers anyway. Mythology was the best we could do, and the criteria were uplift and solidarity and entertainment, not literal truth.

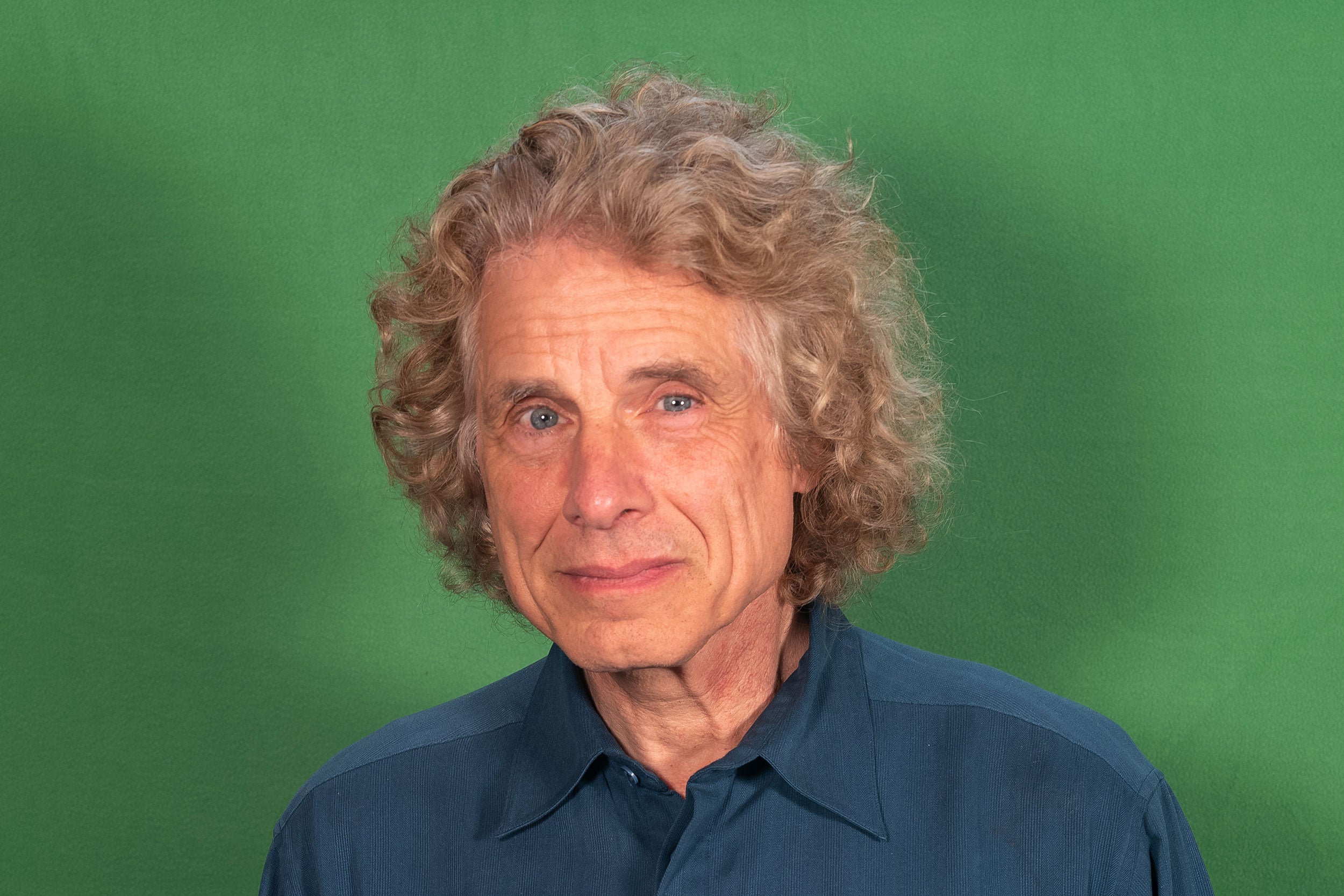

“It’s too easy to blame social media for certain developments, like the rise of know-nothing populism, that might be more attributable to cable news and AM talk radio,” said Steven Pinker.

Photo by Rebecca Goldstein

GAZETTE: Can you apply that directly to the opposition to vaccines and masks? Doctors and scientists would say that those beliefs are pretty irrational, but millions of people share them, despite scientific studies that prove they save lives.

PINKER: Opposition to vaccination goes back to the origin of vaccination itself, because it’s intuitively unnatural, indeed repugnant, to inject a disease organism into your body. The people who do resist that intuition are those who trust the scientific establishment: “Whatever the people in white coats say is good enough for me.” But people who are alienated from the political and scientific mainstream have no reason to doubt their intuitions.

Another contributor is the Myside bias, probably the most powerful of all the cognitive biases, namely, if something becomes an article of faith within your own coalition, and if promoting it earns you status, that is what you believe. It’s somewhat arbitrary which positions get attached to which coalitions, but with Trumpian populism, opposition to vaccines became a rallying point of the political right. It wasn’t always this way. It used to be the tree-hugging Mr. and Ms. Naturals who were suspicious of vaccines — a romantic opposition to science and tech made vaccine resistance a leftish cause. But now it’s more attached to the right. In either case, people are more adamant about protecting the sacred beliefs of their political tribe than looking at the best evidence.

GAZETTE: Do you think that people are more or less prone to rational or rational or irrational beliefs and actions today than in the past?

PINKER: I’m always suspicious of the leap from “Things are bad today” to “Things were better yesterday.” That’s been a theme of my books “The Better Angels of our Nature” and “Enlightenment Now,” where I explain how people mistakenly think, for example, that war and poverty have increased, when the data show otherwise. As Franklin Pierce Adams said, “The best explanation for the good old days is a bad memory.” In the case of irrationality, conspiracy theorizing is probably as old as language. In past centuries, for example, we had the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the Illuminati. One longitudinal study of letters to the editor found no change in the prevalence of conspiratorial ideas in more than a century.

Likewise with belief in the paranormal: Many religions are based on miracles and other paranormal phenomena, and the scriptures reporting them were the original fake news. Before we had social media, we had supermarket tabloids, with sightings of Elvis and babies born talking, and we had urban legends, like the hippie babysitter and alligators in the sewers. Whether there’s been an uptick in recent years with the rise of social media is harder to tell.

There certainly has been an increase in rationality inequality. At the top end, we’ve never been more rational, with developments like effective altruism, evidence-based medicine, data-driven policing, Moneyball in sports. But at the bottom end, there has been a proliferation of nonsense, easily transmitted through social media.

GAZETTE: I am curious about social media, which have been the source of misinformation, as have certain news outlets. How can we use technology to instead help us think or act more rationally?

PINKER: We don’t yet know the answer because social media are so new. It’s too easy to blame social media for certain developments, like the rise of know-nothing populism, that might be more attributable to cable news and AM talk radio. And some features of social media like fake news don’t seem to be major factors in our politics: The studies suggest that it titillates partisans rather than persuading the undecided.

Some developments, to be sure, are almost certainly attributable to social media. Hyperpolarization in politics may be one. Another may be the intimidation of debate and the rise of cancel culture in academia, thanks to the ease of instant demonization and of amassing a shaming mob, as opposed to the slower and more deliberative mechanisms that push back against our irrationality, such as peer review, fact checking, editing, and a reputation for accuracy rather than shareable snark. The friction and slowness in proliferating ideas in the past meant that there were filters and ways of vetting claims for their accuracy rather than proliferating them instantaneously.

GAZETTE: So how can we balance the emotional with the rational in our lives?

PINKER: Emotional reactions like love, rewarding relationships, and an appreciation of beauty are not in opposition to rationality, because rationality is always in pursuit of a goal, and those are clearly worthy goals. When we speak of a tension between rationality and emotion, often what we are referring to is a contrast between immediate and longer-term well-being, like surrendering to impulse or doing what feels good now but knowing it will make you worse off in the long term. There are just goals in different time frames, what economists call discounting the future. Another real tension comes from conflicts between the goals of different people: What’s good for me may not be good for the people I work and deal and live with. There too, we ought to apply our rational faculties to reconcile conflicts among people. That’s what we mean by ethics and politics.

GAZETTE: You dedicated the book to your mother. Why?

PINKER: A lot of academics use “my mother” as a condescending term for “unsophisticated reader” when aiming to attract a broad audience. They’ll say, “Make it simple enough that your mother can understand it.” In my case, my 87-year-old mother, Roslyn Pinker, is not an unsophisticated reader; she’s rational and literate and intellectually sophisticated; she’s just not an academic. I showed her a draft and got her feedback. Making sure she could follow my arguments and understand the explanations was a test of whether my writing was clear and coherent.

There’s also a personal circumstance. When the pandemic began and she was confined to her home, as we all were, it intensified our long-distance interactions, and I think we grew closer while I was working on the book.