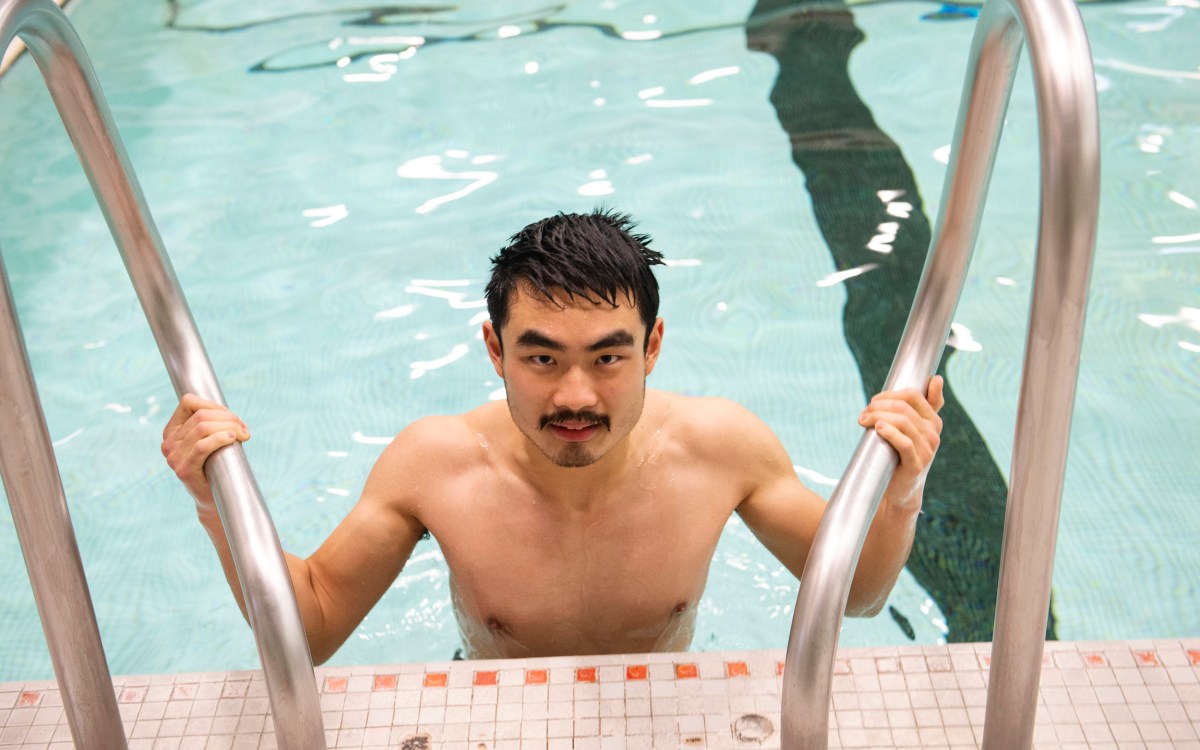

David Abrahams competes for Team USA at the Tokyo Paralympic Games.

Joe Kusumoto/USOPC

Making a splash

Student swimmer David Abrahams wins silver in his first Paralympics in Tokyo

Ever since he was a child, David Abrahams has loved the water.

The newly-minted Paralympian, who won a silver medal in the men’s 100-meter breaststroke event in Tokyo, can trace his passion for swimming back to when he was 6 years old, trying to keep up with his three older brothers.

“I always looked up to my older brothers, who all swam before me,” said Abrahams, 20, a junior math concentrator who lives in Eliot House. “It lit a spark under me, and it’s been one of the predominant forces in my life since I started. I can’t really imagine life without it.”

Abrahams began losing his vision when he was 13. He was diagnosed with Stargardt disease, sometimes called juvenile macular degeneration, a rare inherited illness that affects the retina. As of yet, there is no treatment for it.

“I have a blind spot in the center of my eye, so I have to use my peripheral vision to see things,” Abrahams explained. “Where it affects me most is when I’m training, I can’t see the clock, so I’m relying on my teammates and coaches for that. I’m lucky to have an impairment [where] everything is still manageable for me in the pool.”

He qualified for the SB-13 class in the Tokyo Paralympic Games, which is the least restrictive classification, based on how much an athlete’s disability affects them in the water. He also qualified for the Olympic trials in the 200 meter breaststroke but decided to compete exclusively in the Paralympic event as it would be too difficult to do both games, he said. (The Tokyo games were postponed from last summer because of the pandemic; the Olympics were held before the Paralympics.)

To prepare for competition Abrahams trained 15 to 20 hours a week, taking breaks after large meets to decompress. All of this in addition to his schoolwork. It was a rigorous schedule made even tougher by his Stargardt disease.

“The team has taught me to learn how to compete for something that’s bigger than my own goals and aspirations and a symbol that’s bigger — first the school and then team USA.”

David Abrahams

“With my visual condition, homework can take me two to three times longer than a traditional student,” he said. “You have to learn how to pick and choose and develop mechanisms to make one or more of those aspects easier.”

Abrahams also emphasized the difficulties — and rewards — of dedicating his life to the sport.

“I think a lot of people focus more on the physical side of things [of training], but more than that, the mental and emotional toll the sport can take on you is not something that everyone wants to deal with,” he added. “It’s very emotionally taxing putting the work in every day and spending a lot of time thinking about everything. Swimming has been an outlet to vent a lot of stress and frustration because it allows for that kind of physical activity so you can get rid of some of that weight you’ve been carrying around.”

Some of the challenges Abrahams faced were logistical ones. During spring and summer 2020, there were no pools open in his hometown near Philadelphia due to the pandemic. Abrahams swam in lakes when he had the opportunity and went running and cycling to stay in shape.

Last fall, he moved with several of his Harvard swim teammates to California — first to La Jolla and then to Coronado — where they were able to train in outdoor pools.

“More than anything, it motivated me even more to push through some more difficult things when I was back in training,” he said. “I’d been away from the sport for so long, and it was the longest break I’d ever taken. I was ready to swim by the time quarantine ended.”

David Abrahams competes for Harvard men’s swimming and diving in a meet against Duke University and Texas A&M in 2019.

Billie Weiss/Harvard University

Abrahams is currently the only member of Harvard men’s swimming with a disability. He says his teammates and coaches have been very supportive.

“The team has taught me to learn how to compete for something that’s bigger than my own goals and aspirations and a symbol that’s bigger — first the school and then team USA,” he said. “It takes a while to move out of the frame of competing for only yourself.”

In the coming season, the team is aiming to place in the top five in the NCAA championships. The last time Harvard captured a title was in 1989.

“I want to be a contributing member of the team and be able to pass on the legacy to the next generation of athletes here,” Abrahams said.

He’s also already looking ahead to the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris. While he would love to represent the U.S. in both the Olympics and the Paralympics, he may again be faced with the choice to compete in only one of the Games.

“When it comes down to it, I’m going to go with the option that allows me to swim for the longest period of time and the highest level of competition,” he said.