New York City, Sept. 11, 2001.

AP File Photo/Chao Soi Cheong

Where were you when it happened?

Faculty and staff from across the University reflect on the day and the aftermath

One was at the World Trade Center. Another was a few blocks from the White House and lived near the Pentagon. A third was on the West Coast, where it was early in the morning. Still another was in the South. Others were on campus. The Gazette asked some Harvard affiliates from across the University where they were when the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks took place, and how they think about that day two decades later.

Annette Gordon-Reed

Carl M. Loeb University Professor, Harvard University

I was in the concourse of the south tower in Sam Goody’s record store to buy a new Walkman radio/cassette player. I had just returned from taking my kids to school, having come up from the subway. I heard a loud “whump,” and things began to fall around us. I ran out with everyone else and ended up in an area that gave me a view of the north tower, which had been struck. Horrific. Things were falling down from the collision. We were told to stay put. I remembered something my father told me when I was a little girl: “If you come upon a scene where there are lots of ambulances and evidence of a disturbance, go the opposite way.”

I decided against staying put and went out through a concourse connected to the south tower — opposite to where I was — to find my husband. We lived across from the World Trade Center, and I knew he was out in front of our building handing out political literature, as it was primary day. It was a pretty grim scene running through the debris, shoes, suitcases, and other evidence that a plane had crashed. By the time I got to the building, I turned around and saw a second plane fly into the south tower. We all took off running, and I heard my husband calling me. We quickly decided to leave the area, which was chaos as people were jumping from the towers.

We started walking north to get to our kids. I stopped at my office at New York Law School to call my father — only landlines were working — to let him know I was OK. As we talked, the first tower came down, and all our power went out. We left and resumed walking uptown. We caught a bus that took us to 59th Street. Then we walked up Central Park West to 91st and Columbus, picked up our kids, and got a hotel room.

I remember it as a horrific day. I saw lots of people die. I felt blessed because my kids could have been orphaned, and they were not. I felt so sorry for the people who were trapped in those towers and lost their lives. It was bewildering at first because the day was so beautiful. At first, I couldn’t see how a plane managed to hit the tower. When I saw the second, I knew that it was deliberate, of course. But it changed the course of my family’s life. We had lived downtown from the time we moved to NYC after graduating and getting married at Harvard-Epworth Methodist Church. After the attacks we moved uptown close to our kids’ school. I felt sad about losing our community. But others lost so much more.

The memory is very vivid. In movies when people are in danger, the characters sometimes seem flustered and confused. I don’t ever remember being clearer about what I had to do that day. I was shocked when I found out how close the time was between the first and second plane, the time that I was running around in the building and then out of it over to where I lived. It seemed like a long time had passed. But it hadn’t.

For a long time after that the sound of a plane was frightening. There are visceral feelings — the awful things seen, the smell of jet fuel, the knowledge that I just missed being in the area under where the second plane hit. You know that you made choices and that you were lucky. It could have been very different. What started as a beautiful day turned into a horror show.

Soyoung Lee

Landon and Lavinia Clay Chief Curator, Harvard Art Museums

I was in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City on the morning of 9/11. I had just started my year of fellowship in the museum’s Asian Art Department. Staff had begun to arrive at work, and I remember a colleague, who had been listening to the radio, calling out that two planes hit the World Trade Center. My brain didn’t — couldn’t — compute what that meant. A plane hitting a building? Even as news confirmed the event as a terrorist attack, and images and details were released, the shocking reality was simply unfathomable. You couldn’t tie it to any previous experience or knowledge — nothing like this had ever happened before.

In truth, much of that day is now a bit of a blur. But I do remember walking across Central Park after we were sent home from work and seeing billowing smoke from downtown even at that distance. And I remember the feeling of unreality, of shock and disbelief, a cognitive disconnect. And anxiety that I couldn’t get home to my husband in New Jersey. I think virtually all modes of transportation out of and into the city were cut off that day. Two years later, when the so-called Northeast Blackout of 2003 hit New York City on a blazing August day, everyone initially thought it was another terrorist attack. I was again in the Met Museum (this time as a curator) and again couldn’t get out of the city and ended up walking miles for temporary shelter at a friend’s home. That time, with the 9/11 incident still vivid in my mind, I felt visceral dread and panic. At times I find the feelings of those two days conflated.

I imagine that for those born after 9/11 the event is abstract. The now standard routines of post-9/11 travel — taking your shoes off, no liquids in your carry-on, even TSA pre-clearance — were not normal in pre-9/11 days and represent the more mundane facets of a world forever changed by those terrorist attacks. It’s actually staggering to realize it happened 20 years ago. My own experiences were circumscribed by the fact that I wasn’t at ground zero. I can’t imagine the seismic shift experienced by those who survived and the pain and depth of grief for the families who lost their loved ones that day.

Jill Abramson

Senior Lecturer on Journalism, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

On Sept.11, 2001, I was the Washington bureau chief of The New York Times. The Pentagon, one of the terrorists’ targets that horrifying day, was just a mile from my house. The impact of the plane hitting the massive building bounced my son out of his bed. I was already at work. The White House is just a few blocks from the bureau. At one point we thought it too might be hit. I began compiling our noon list, the list of stories coming from Washington reporters. It grew and grew, the most stories the bureau filed in a single day. Eventually, I had it framed, and it still hangs right outside the bureau chief’s office. We chronicled everything from intelligence failures to the personal stories of those killed. One of the workers killed at the Pentagon was the brother of a New York-based editor. He waited with us for days while his brother’s body was found and identified. I will always remember his stricken look as he sat, waiting.

I didn’t leave my desk until I finally drove home at 3 a.m. I passed by the Pentagon, glowing orange, and still burning. As I neared our house, almost every home had an American flag outside. When I pulled into our driveway, I saw that my husband had put up the absurdly large Stars and Stripes that we pulled out every Fourth of July.

It was only then that I felt the emotional impact of the day and the terrible loss for our country. I sat in my car and cried. Then my phone rang, and it was an editor in New York. She told me the phone lines were down in Manhattan. We would have to divert all calls through Washington, so the bureau had to be reopened. The news never stopped that night or for scores of nights thereafter. Tanks appeared on the street outside the bureau. A huge box arrived from the Times containing survival equipment, including flashlights and gas masks. My colleagues, all the Washington editors, reporters, and photographers, did amazing work as did the entire paper. No one was surprised when the Times won seven Pulitzer Prizes that year — a record that still stands.

For me, the meaning of that day is why it is so important to provide the best, authoritative information to a stricken and worried world. In the midst of tumult, tragedy, and war, The New York Times provided a lasting public service that continues through time. It was an honor for me to be a part of its coverage on 9/11.

The attack on the Pentagon killed 184 people.

AP File Photo/Will Morris

Dana Born

Lecturer in Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School

Like virtually every American of age that day I remember exactly where I was and what I was doing — in my office at Bolling Air Force Base in D.C. preparing to hold a commander’s staff meeting. I also recall just how beautiful that Tuesday morning started while driving to work across the Potomac — sparkling waters, beautiful blue sky, and a cool, brisk early autumn breeze. Hours later the landscape, nation, and world were changed forever. My heart sank as I looked from my office window, across the Potomac and at the Pentagon in flames … with a cloud of thick black smoke and ash snaking down the river. It was not long afterward that I heard what no American should ever have to hear — fighter jets on patrol screaming overhead to protect our nation’s capital.

Despite these vivid memories, what I remember most is how this nation responded when our freedoms were attacked. I was inspired by the selfless acts of courage by service members, firemen, policemen, emergency responders, and the general public. When we were shaken by the worst of humanity attacking the Pentagon, the military (and others) responded by showing us the very best of humanity. I am particularly grateful for the role sailors, soldiers, airmen, and Marines played in evacuating our two daughters from the Pentagon day care center that morning and assisting other wounded out of the burning building. When every instinct leads one to run out of harm’s way, they chose to run into harm’s way. Although many find this difficult to understand, for members of the military community it comes as no surprise since this is the nature of who they are.

Like other families who experienced 9/11 on such a personal basis, our life journeys were forever changed. My husband resigned from his second career to become a stay-at-home dad for the next 18 years. I decided to continue serving since I felt that is where I could best contribute. And most poignantly of all, our two daughters decided to join the military to live a life filled with purpose and be part of something greater than themselves.

We must never forget 9/11, and most especially, those who made the ultimate sacrifice in giving their “last full measure of devotion.”

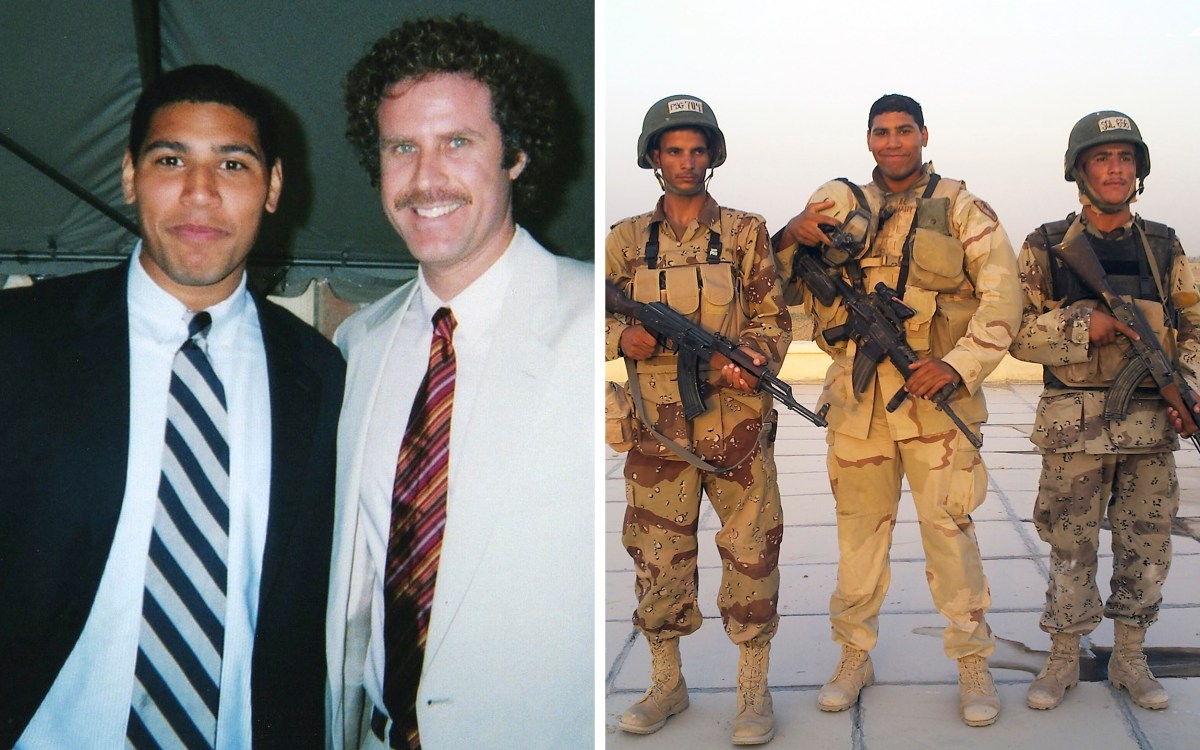

Khalil Abdur-Rashid

Muslim Chaplain at Harvard University

It was my first day on the job as a social worker for the state of Georgia. I asked my supervisor for permission to attend the Friday Prayer on my lunch break. She asked about the significance of the Friday Prayer, and I explained that it was a religious obligation for Muslims in Islam. She then asked me to explain a little bit about what Islam was, out of curiosity, and before I had a chance to answer a co-worker entered the office and exclaimed that a plane had just struck one of the World Trade Center towers and that the tower had just collapsed.

My conversation about Islam with my boss on the first day of work had been hijacked by the terrorist attacks, and it would forever change the trajectory of my life. That day was a day filled with an eerie feeling that the U.S. would be going to war and the fear of what it would mean for Muslims who might experience collective punishment. Airplanes weren’t the only thing hijacked that day. The lives and futures of millions of Americans were stolen as well.

Before 9/11, I was raised in a community that had primarily been focused on being Muslim through the African American experience of the struggle for racial justice. Fighting racial injustice and tending to the marginalized in our inner-city community was the major priority.

After 9/11, American Muslims became united in struggling against the stigma of being perceived as a security threat, whether on account of the hijab, the beard, a name, or wearing a turban or kufi cap. Opportunities emerged for Muslims in America to engage in real dialogue and conversations about Islam. This required a certain knowledge about what Islam says about various topics; mere cursory knowledge about the five pillars of Islam was not sufficient to allay fears rooted in ignorance and stereotypes.

This led to a migration by many African American Muslims abroad for education about Islam. I quit my job as a social worker and traveled to the Middle East, finally landing in Istanbul, Turkey, for Islamic seminary studies. After completing my seminary studies, I thought it prudent to combine my training with academic studies of Islam, which later led me to university chaplaincy.

It was through my journeys that I realized that as an African American Muslim, I had a responsibility to lead and represent the best of what my faith tradition and my community stands for. I believe in many ways that this realization exists in most of the American Muslim students I encounter today and therefore, in hindsight, the experience of 9/11, while traumatic on the one hand, resulted in both an individual and communal transformation on the other — a great awakening of sorts for American Muslims. This Great American Muslim Awakening entails diligently working to transform hate into hope through a devotion to enhancing human and civil rights. In my experience, such a struggle is actually paradigmatic of being an American Muslim — and part of what it means to be human!

Victor Clay

Chief of Police, Harvard University Police Department

I was living in Los Angeles at the time and working for the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department. It was 6 o’clock in the morning on the West Coast, and my wife was about to get our girls ready for school. I worked the evening shift the day before, so I was out like a light. Suddenly, she ran into the room and said, “Turn on the TV. I don’t know if this is real or not.” I turned it on, and they were showing the first tower on fire. I recall thinking, “This is real.” And then I watched the plane hit the second tower.

I remember this chill coming over me. My first thought was, “This is no accident; this is an attack.” We lived close to Los Angeles International Airport at the time, and I wondered if it was a targeted thing for all the big airports. We weren’t near downtown, so I felt relatively safe, but as it started to develop, I just remember feeling this numbness. I realized that this was happening on continental United States soil, and we were actually experiencing one of those historic moments. But I wasn’t able to take it in like a civilian because the phone started ringing.

I remember thinking, “What if I get dressed and leave the house and never see my family again?” But then you just click into work mode, and you go from there. My family knows my job well enough to say, “We love you. We’ll see you later.” And I just kept in touch with them every few hours. But it was one of the craziest internal feelings I’ve ever had as a citizen of the U.S. and as a first responder.

In the days that followed, we had to monitor protests, stop attacks on mosques, and protect folks just walking down the street, because if they were wearing anything that might indicate they were of the Muslim faith, they could be a target. We were probably given a 48-hour window to take the national perspective and say, “Oh, my God, America was attacked.” But pretty quickly it became, “Oh my God, now America is turning in on itself. And we need to protect our folks from bigotry and hate.”

A lot of my colleagues at the time were very angry and didn’t always distinguish the terrorists from the others living in those countries. I was always bothered by that, because the innocents who had absolutely nothing to do with the attack were being forced into the enemy category. I realize war is ugly and dangerous, and lives will be lost, but after 20 years and 2,500 or more U.S. military members being killed in Afghanistan, not to mention the numbers of allied service members killed, and the hundreds of thousands if not millions killed in the Middle East … what was it all for?

Steven Pinker

Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

At 10:28 a.m. on Sept. 11, I watched the north tower collapse. At 2 p.m. that afternoon I was scheduled to lecture in Introduction to Psychology to 300 undergraduates, half of them freshmen. On top of the shock and horror, I was faced with a decision. I knew that the events would be even more upsetting to them —18-year-olds who had begun university life just the week before — than they were to me. Soon enough the issue was forced by the expected email from the head TA: Would I be canceling the lecture?

I told her the lecture was on. My decision involved not just the pedagogy of the lecture content but of the decision itself. The biggest part of adulthood is fulfilling one’s responsibilities in the face of adversity and stress. Students in earlier generations continued their education during the Civil War, two World Wars, and other national traumas. I had received correspondence from young people in poor and violent parts of the world who were envious of my students’ opportunities. Parents or benefactors had paid exorbitantly for their privilege. Though I certainly would not penalize anyone who was especially vulnerable or who had lost a loved one, I decided it was reasonable for everyone else to collect themselves, summon their concentration, and carry on with their adult lives, as I myself would conspicuously be doing.

Smaller decisions faced me. My prepared lecture was an introduction to Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis and B.F. Skinner’s behaviorism, and it did not miss the many opportunities those theories provide for levity and satire. I quickly edited my PowerPoint to excise the cheekier jokes that would seem to make light of the gravity of the moment, while keeping just enough whimsy to convey that we were still permitted to be human.

No one complained. I wonder whether the decision would be controversial today, when conceptions of victimhood, vulnerability, and trauma have been expanded and valorized.

President President Lawrence H. Summers addressed a crowd of students, faculty, and staff in Harvard Yard in the hours after the attacks.

Harvard file photo

Drew Faust

Arthur Kingsley Porter University Professor, Harvard University

President Emerita

I was just beginning my deanship at Radcliffe when 9/11 happened. I had come the previous January, and my first new crop of fellows was to gather for orientation on the 12th. Many of them were in the air on the 11th and got stranded all over the place — I remember one European ended up staying with nuns in a convent in Canada until flights resumed many days later.

It was, as everyone notes, a gorgeous crystal-clear day. I had just arrived in the office in Fay House when someone came rushing in to say that a plane had hit the tower of the World Trade Center in New York. I, at first, thought it might be just pilot error, but almost immediately, the Radcliffe executive dean, Louise Richardson, whose academic expertise is terrorism, said that this was certainly a terrorist attack. Throughout the day, her clear-eyed and informed perspective helped keep us calm and able to deal with the many issues we faced.

First and foremost was the effort to get news about everyone’s whereabouts and safety and that of their relatives and friends: Who was in NYC, or on a plane, or stranded somewhere? We also were completely uncertain about how many more attacks there might be and where they might occur, so the anxiety level was very high. I remember that late in the day, there was a gathering in Tercentenary Theatre — people came and stood by the steps of Memorial Church, and there were prayers and music of some sort. A sense of community was consoling.

Thinking back, I would say 9/11 changed everything. It led us into the two terrible and purposeless wars that are only now coming to a close. It shattered American confidence and complacency, creating a sense of national vulnerability that has provided fuel for some of the extremes of American politics we see today. And much more …

Share your own Sept. 11 memories and reflections with editor Ryan Mulcahy: ryan_mulcahy@harvard.edu. If we hear from enough readers, we’ll publish the responses.