Andres Mendoza ’23 has written a paper for his Expository Writing Class about how Harvard dealt with the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Keeping students on campus for their health and safety?

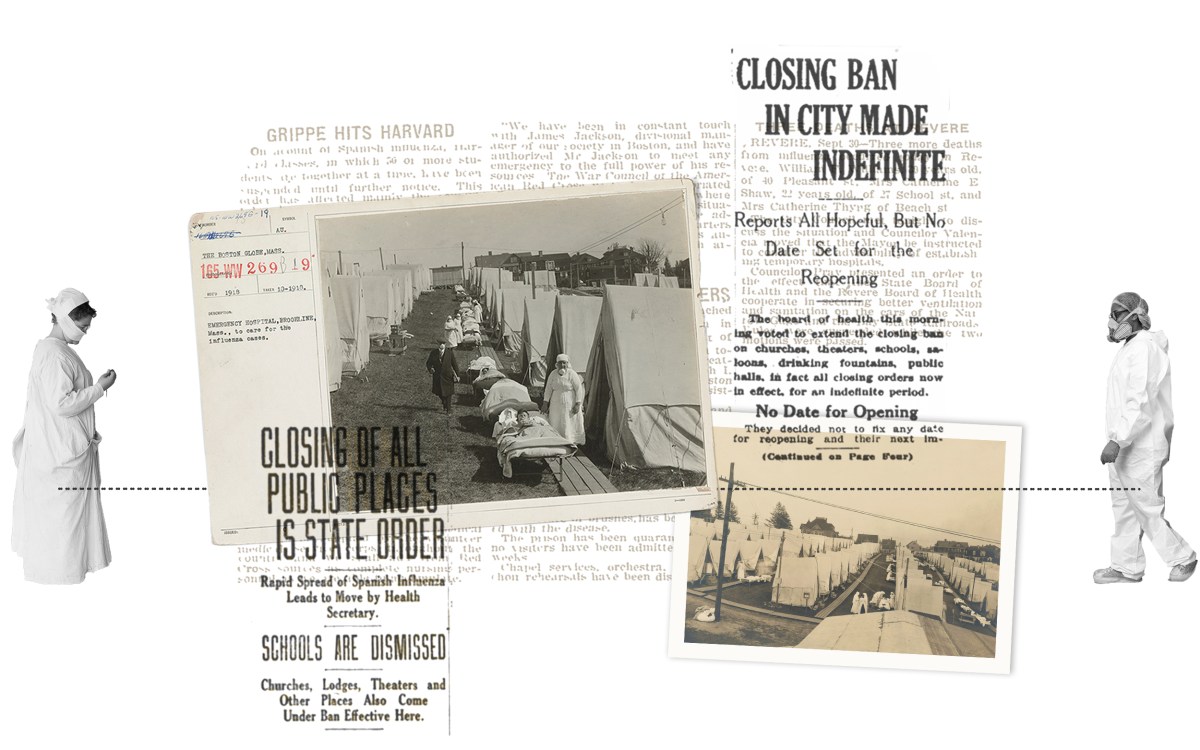

Student’s paper finds resonances between the 1918 pandemic and one a century later

Andres Mendoza ’23 wondered whether Harvard was heeding the lessons from history when it ordered students to evacuate the campus last March as the COVID-19 outbreak began to spread.

The then-first-year, who returned to his native Panama as the campus began to shut down, wanted to find out how the University had dealt with the 1918 influenza pandemic. And he chose to do what any curious student would do: He wrote a paper about it.

Events can be better understood from a historical lens, he wrote in his paper “Addressing Pandemics: 1918” for his expository writing class. Learning about the pandemic a century ago gave him insights into our current one, and along the way he learned something else.

“The biggest takeaway for me was that we should not ignore history,” Mendoza said on a Zoom call from Panama. “What we can learn from past history is the knowledge and ability to look back to inform our decisions and actions toward the future.”

As Mendoza plunged into his research, he became fascinated by the similarities and differences between past and present, including the controversies over the decisions taken 100 years apart. “It was interesting to study something that was being repeated,” he said.

In both cases Harvard decided to carry on with classes. But in 1918 students remained on campus; last March, students were sent home, and campus closed.

More than 2,100 were enrolled for the 1918‒1919 academic year, according to University records. Abbott Lawrence Lowell, President of Harvard (1909‒1933), justified his decision, saying the University was “acting under the best medical advice.”

In fact, in a letter to a student who questioned his decision, Lowell explained that his first concern was actually their health and safety. “The medical men thought it was better not to close the college; that to send the men here back to their towns would have a bad effect; that they could be better looked after here than they could if dispersed,” Lowell wrote.

The University implemented measures to contain transmission of the virus on campus. Classes were kept small, barracks uncrowded, and administrators focused on “careful supervision and treatment of students.” Lowell ordered that anyone who sneezed or coughed during lectures had to be quarantined.

The measures helped keep the epidemic under control. In his report to Lowell, Professor of Hygiene Roger I. Lee wrote, “The entire college population was examined, and quarantine and isolation measures were adopted when necessary. While these precautions did not eradicate influenza from the University, nevertheless the University suffered much less than most communities.”

A report by College physician Marshall H. Bailey provided more details about the effects of the pandemic on students. Bailey said 258 were treated for influenza on campus at the Stillman Infirmary. Sixty-one students developed pneumonia, and six died. Bailey attributed the low mortality to the “Harvard system of medical supervision.”

“With few exceptions these 258 students sick with influenza were put to bed before they felt much ill,” said Bailey, “often before they were willing to go until the importance of early care was explained to them.”

Mendoza relished digging into the archives of The Harvard Crimson, papers published in public health and medical journals, and other old records, but the highlights of his findings were the letters and accounts written by Lowell. “You could basically see that he wasn’t sure what decision to take,” he said.

Reflecting on President Larry Bacow’s decision to send students home last March, Mendoza said in the beginning he was frustrated, like many students, but after his research, he agreed that it was the right thing to do.

“What I learned is that the sooner you act and intervene and restrict social gatherings, the sooner you will be able to get on with post-pandemic life,” said Mendoza.

Mendoza, who spent part of his freshman year and all of last fall in Panama, returned to campus this spring. The Cabot House resident said he very much looks forward to the fall.