Kaleidico/Unsplash

How COVID experiences will reshape the workplace

Scholars say shutdowns and remote work yielded insights for employers, workers

Now that COVID-19 vaccines are finally here, employers have begun looking ahead to an eventual full return to the workplace in the coming months. But even though their offices may look exactly as they did last spring when most white-collar organizations shifted to remote operations, they will find that things will be very different, say Harvard Business School (HBS) faculty who study the work world.

The pandemic has sped up macro trends in consumer behavior, business management, and hiring. That, along with insights gained by months of adjustments to work roles, schedules, routines, and priorities, have prompted employers and employees to reconsider many default assumptions about what they do along with how and why they do it.

The changes will vary by field and employer, but experts predict flexibility and safety will be top priorities that could bring, for instance, a rethinking of the five-day work week and the way employees earn and spend vacation time. Also, the power dynamics between employers and employees will shift as each reappraise the other’s roles in light of what they learned during the pandemic. And organizations will likely give more attention to employees’ mental health care, getting a closer look at the daily personal pressures their staffs face.

“It’s the Next Normal we’re headed to, not ‘back to normal,’ and that, for a lot of companies, is going to feature changes in work practices, changes in employee expectations of their employer, and companies learning from this duress about what they can do to be more effective and efficient and attractive employers,” said Joseph B. Fuller, professor of management practice and co-founder of Managing the Future of Work project at HBS.

One of the first challenges businesses face will be the question of whether to ask, or even insist, that employees be vaccinated before coming back to work. For a variety of reasons, not everyone will agree to do so, leaving employers to struggle with how to protect their other employees, customers, and clients, while not violating civil rights laws.

One year into the pandemic, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the federal regulatory agency that oversees private sector workplace safety in all 50 states, had not established national COVID safety standards under President Trump, leaving individual companies and industries, like meatpacking, to set their own protocols and policies.

“It’s bananas to entrust our public health decisions to disaggregated, atomized employers making their own decisions about what’s good enough and what’s not,” said Terri Ellen Gerstein, director of the State and Local Enforcement Project at Harvard Law School’s Labor and Worklife Program. “With OSHA abdicating its responsibility, that’s been happening in too many places.”

“It’s the Next Normal we’re headed to, not ‘back to normal …” said Joseph B. Fuller, co-founder of Managing the Future of Work project at Harvard Business School.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

President Joseph R. Biden Jr. signed an executive order Jan. 21 directing OSHA to issue revised COVID-19 safety guidance for businesses within the next two weeks. The order also calls for the agency to consider setting emergency temporary COVID safety standards, including whether masks should be required in workplaces, by March 15; a top-to-bottom review of OSHA enforcement efforts, which worker advocates, including Gerstein, have called lax; and begin focused enforcement on firms engaging in large-scale violations. The order did not, however, address the issue of whether workers could be required by employers to receive vaccinations before returning to their workplaces.

Employers should “absolutely recommend” employees get vaccinated, if that’s their goal, but not demand they do so, advises Ashley V. Whillans, a behavioral psychologist at HBS who recently surveyed 44,000 remote workers in 44 U.S. states and 88 countries to study how the pandemic is affecting workplace attitudes and behaviors.

“Make it an opt-out policy but have a formal process for opting out that doesn’t involve having to email your boss or talk to a specific manager in the office. We’ve shown in other contexts that having formal policies that don’t involve speaking to another person who’s directly responsible for your compensation can help employees feel confident in making decisions that are more aligned with their personal values and less likely to make decisions based” on how others may perceive them, she said.

“I think the workplace issues in our country so often are dealt with in this zero-sum way, where worker interests are seen as adversarial to business interests,” said Gerstein. “And this is really a situation where everyone has to make sure that people are safe at work.”

That’s just the beginning. The pandemic has jolted the foundation of a workplace model that had been relatively unchanged since the late 1920s: employees traveling from home to a workplace five days a week, between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., to complete their obligations.

Since March, employers have had time to reassess which jobs and employees are truly essential to the success of their business, while workers have been able to reconsider the daily demands their jobs place on their lives, such as travel, commuting, or following rigid work day schedules, and whether they’re still willing to tolerate them, said Fuller, who also co-chairs the Project on Workforce with Harvard Kennedy School and Harvard Graduate School of Education faculty.

That’s led to once less-common trends like workplace flexibility, “work from anywhere,” and virtual meetings becoming more mainstream. With broader acceptance, Fuller expects many knowledge-based industries will move to a four-day work week, cut back significantly on travel for internal activities like training and sales meetings, and do away with vacation policies tied to an employee’s years of service. Instead, workers could take as much time off as they wish provided their work is done, an approach first embraced by Silicon Valley firms.

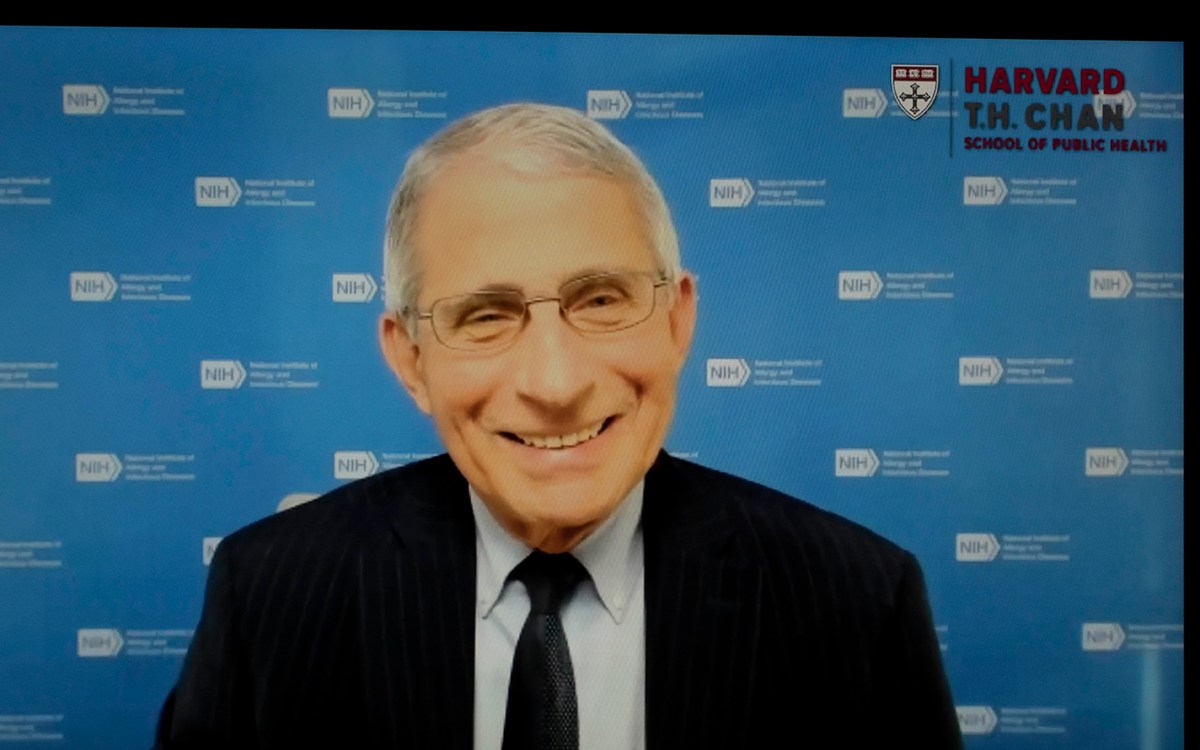

In the coming months, employers will need to provide more support to employees than ever before, said Ashley V. Whillans, a behavioral psychologist at Harvard Business School.

Courtesy of Ashley V. Whillans

It has also disrupted the balance of power at work. Where employers used to set the terms of employment — where, when, and how the work gets done — Fuller said the question of “who decides” is now much more up for grabs.

Organizations that offer employees the ability to work flexible workday schedules, to choose when and how they come into the office, and that have adopted increased COVID safety precautions score highest with their own workers, Whillans said her COVID survey data shows. So as employers prepare to reopen, they would be wise to maintain and emphasize work flexibility and safety regulations and allow staff to come back to the workplace at their own discretion.

“Organizations need to clearly communicate with employees their expectations for employee engagement, how often they assume that employees need to come in, and if there are any changes to office policies, like lunches or common spaces not being available, they should clearly communicate this as a safety precaution,” said Whillans. Too often, firms “under-communicate” out of fear of how messages will be received, when research shows that conveying as much information as possible, being almost “overly transparent,” helps businesses win trust.

One effect of the pandemic that will persist long after businesses reopen is employees’ mental health, Whillans and Fuller say.

The virus’ physical, social, and economic impacts have not been felt equally, which has led to “significant” mental health strains, including increased anxiety and depression, on people at every level within organizations and across industries. Even those who did not become sick or laid off report worries about their own health and that of loved ones, the possibility of losing income, or just the constant uncertainty over when, or if, their lives will return to normal, said Whillans.

“This is really a situation where everyone has to make sure that people are safe at work.”

Terri Ellen Gerstein, Harvard Law School

“We are observing high levels of burnout and stress,” even among workers who still appear to be high functioning, said Whillans. With the current economic recession, employees are “disincentivized to speak openly and honestly about their stress and frustration” out of fear, or they cope by minimizing its effect with comparisons with others who seem to be worse off.

“Workplaces don’t have a good grasp on the depths of the stress that employees are experiencing,” she said.

Fuller said many business leaders got a “real wake-up call” about the ubiquity of mental health issues among employees during this work-from-home period, especially the stress and depression caused by the pandemic, and “it’s been sobering” for them to see firsthand how acute the effects can be. It’s also given many a better understanding of the daily complexities their staff members must navigate, like caring for young children or elderly parents, just to be able to get to the office and be productive. “It’s caused them to have to reflect on the totality of their workers’ life experience,” he added.

In the coming months, employers will need to provide more support to employees than ever before, either in the form of temporary relief, job sharing, or other incentives, in order to help them deal with the increased stress they’ve been experiencing, said Whillans.

More like this

“Organizations are likely to miss thinking about well-being as one of the decision-making factors that goes into whether they open and how they open,” she said. “I would really underscore the importance of organizations not overlooking employees’ health and safety concerns because burnt-out employees are going to be less productive and more likely to quit.”

Virtually every business has discovered new things, both good and bad, about themselves over the last 10 months, but the smartest ones will have used the time to also ask new and different questions of themselves, said Fuller.

“They should use their learning from this period to ask themselves questions like: What have I learned about what allows people to be productive and have a better quality of work life? And, should I be revisiting the way we do things around here based on that? What have I learned about communicating with my workforce? And what do I want to make sure we continue to do because [the] practice that we developed in this crisis is better than what we were doing?”