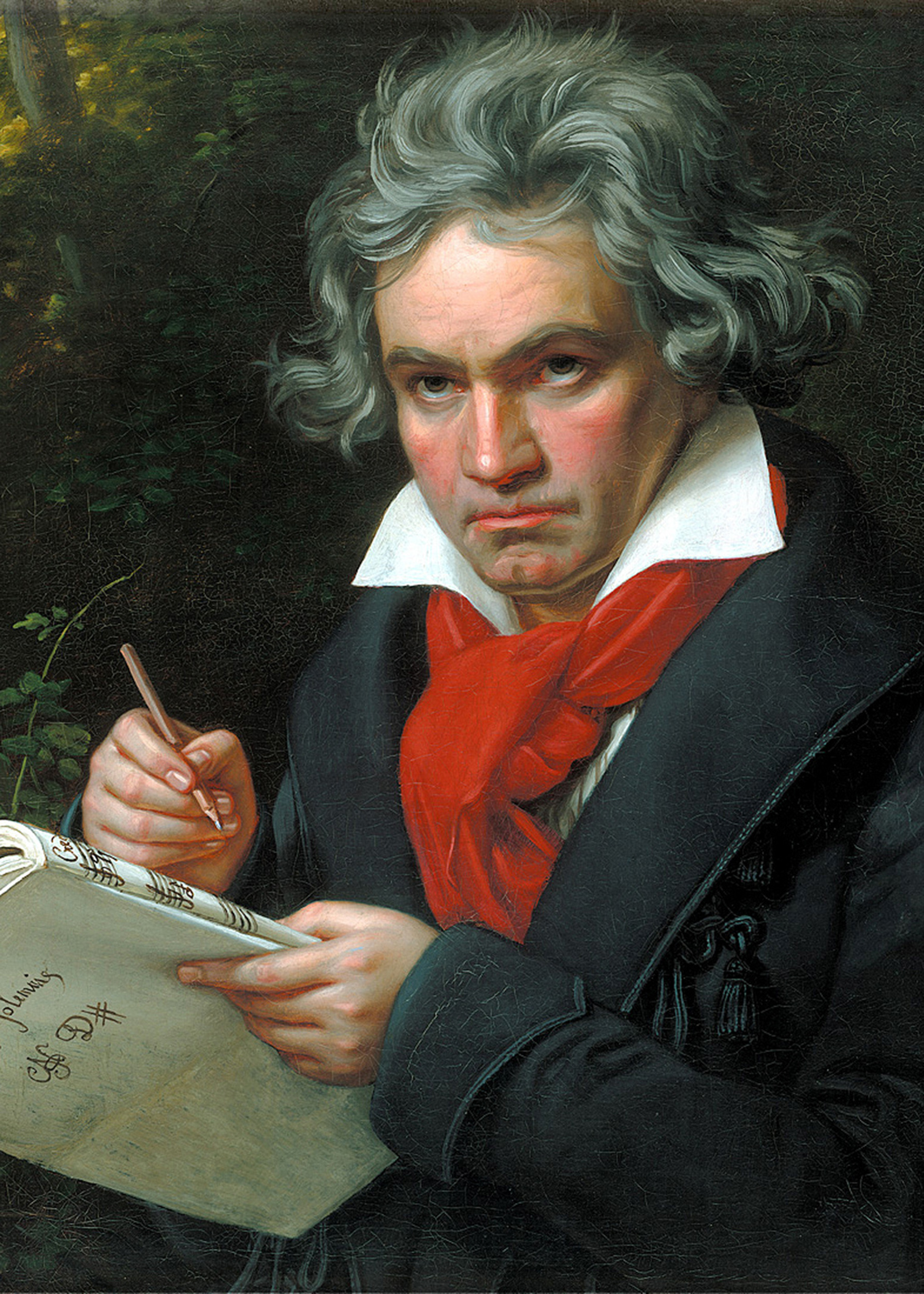

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820.

Wikipedia/Public Domain

Ludwig van Beethoven wrote music that has endured for centuries. Interpreted by classical musicians and contemporary artists alike, his work is found in everything from disco hits to movie scores to TV shows and rap songs. In his own day, the fiery, tempestuous composer was a skilled improviser and innovator, and the first major composer to include voices in his symphonic works. On the 250th anniversary of his birth in December 1770, six Harvard-affiliated composers reflect on the continuing significance of his work.

Yosvany Terry

Senior Lecturer on Music and Director of Jazz Ensembles

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Without a doubt, Beethoven was one of the most celebrated composers of his time. I believe he is one of those figures that you cannot escape, in the same way you can’t escape Mozart, Bach, Brahms, Debussy, Ravel, Prokofiev, Shostakovich. Studying music without studying Beethoven is like trying to become an opera composer without knowing Mozart, who contributed so much.

Beethoven is very interesting because he represented that special connection between what historians would call Classicism and Romanticism, and you can see this transformation/connection in his music. Another thing that fascinates me about Beethoven — in addition to his mastery of both composition and musical transformation — is that he was a great improviser. You can hear that, but you really see it when you study his music. It is known that he was an incredible improviser during his time and that ability, I think, brought freshness to the natural way in which he was able to take his music material and develop it over and over. I consider this to be one of the aspects that connects him with some genres of music that have improvisation at its core, and as a jazz and contemporary musician who studied classical music, I take a lot of inspiration from it. When you listen to his sonatas, piano trios, string quartets, symphonies, you are just facing a genius, and you have to stop and celebrate his ingenuity as a composer.

Piano Sonata No. 29 (“Hammerklavier”) (Peter Bradley-Fulgoni)

Beethoven also helped to revolutionize the pianoforte, which is one of the ancestors of the piano as we know it today, with his compositions and musical explorations. The “Hammerklavier” sonata is a testament to how he pushes the boundaries of the instrument searching for new ways of expressions and sonorities. But to focus just on his piano work doesn’t really capture the genius composer, because when you hear his music, you realize he really understood what for us is the ultimate instrument, the orchestra. He understood it from the inside out and in incredible detail.

As a composer, you go back study the scores, analyze the music, and learn from the composition process and the principles that earlier composers created for their own work. Beethoven is one of the key figures you have to grapple with, like Bach, Mozart, Ravel, and Bartok. As a jazz artist, you need to study Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and John Coltrane. You cannot skip them.

Yvette J. Jackson

Assistant Professor, Department of Music

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

The first eight measures of the second movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 are a magnificent whirlwind of energy. I cannot resist listening to a recording of the Molto vivace scherzo in D minor without repeating the opening sequence six or seven times before allowing the movement to unfold; it’s an attempt to sustain the feeling that it brings me. The immediacy with which Beethoven demands the listener’s attention is something I think about with my own compositions. I also think about who gets memorialized and who does not and the reasons behind these decisions.

While the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth is being celebrated by different communities around the world, my attention is on George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, the Afro-European virtuosic violinist who inspired Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” sonata. Beethoven ended up removing his name from the dedication and, like many Black musicians and composers, Bridgetower’s contributions have been forgotten or obscured until recently. As efforts to resurrect these histories are being expanded by artists, scholars, and artist-scholars, I am influenced by FORGEWITHGEORGE and its commissioned composers; it is a music project Nicole Cherry began in 2016 to celebrate Bridgetower’s legacy. Cherry, assistant professor of violin at the University of Texas at San Antonio, is premiering a new body of repertory for solo or chamber violin each year until 2033, the 200th anniversary of the Slavery Abolitionist Act in England. (Bridgetower lived in London.) While audiences convene for online lecture series and virtual concerts to commemorate the works of Ludwig van Beethoven, I hope the same audiences will devote an equal level of enthusiasm toward learning more about the artists of color and women who have contributed without receiving the deserved recognition.

Matthew Aucoin ’12

Director, American Modern Opera Company

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

One thing that sets Beethoven apart, especially from the Viennese Classical music of the generation before him, is its sheer explosiveness. You often have the sense, with the very first note of a Beethoven piece, that it bursts into existence as a result of some uncontainable pressure that must have been building for a long time before the piece was born, a pressure that finally became unbearable.

Coriolan Overture (Fulda Symphonic Orchestra, Simon Schindler)

Just listen to the chords that open the “Eroica” Symphony, or the “Coriolan” Overture. These pieces begin with a tearing, rending gesture — some fabric is being ripped, some curtain is being torn down so that we can gain entry into a new space. That was a radical gesture, fundamentally different from the way an immediate predecessor like Mozart would begin a piece. A lot of Mozart pieces seem to emerge fully formed, as if through a virgin birth. With Beethoven you can feel the struggle.

And I think that sense of struggle, of effort, is part of what makes Beethoven’s music so affecting. It’s magnificently wrought, of course, but it almost never feels easy. There is clearly a human subject at the center of the whirlwind, standing calmly in the eye of the storm, and it can be a powerful experience, as you play Beethoven’s music or listen to it, to try to identify with that subject.

Vijay Iyer

Franklin D. and Florence Rosenblatt Professor of the Arts

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Beethoven has occupied an outsized place in the U.S. zeitgeist for as long as I can remember. An arrangement of his Symphony No. 5 even showed up on the “Saturday Night Fever” soundtrack in 1977, when I was 6. Harvard’s string quartet in residence, the Parker Quartet, put out a spectacular recording last year of three of Beethoven’s quartets. Even though I grew up playing and enjoying his music, I always felt a little removed from his legacy. The composer’s presence in the American imagination plays into a fantasy of continuity with European culture, which is also imagined to be “pure,” free of any non-European presence.

Symphony No. 5, first movement (Fulda Symphonic Orchestra, Simon Schindler)

But what we know of Beethoven’s world complicates that picture, even beyond theories around his ethnic heritage that I won’t get into here. The fact is that all of Europe participated in the economies of imperialism and enslavement, and the continent was home to many individuals who were born of those violent histories. Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9, more commonly known as the “Kreutzer” sonata, was initially composed not for violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer, but for the composer’s friend, the Afro-European violinist and composer George Bridgetower. In 1803, Bridgetower performed a dazzling premiere of the piece, with the delighted Beethoven at the piano; but the two musicians quarreled after the concert, and the composer decided to revoke his original dedication.

In recent years Bridgetower has been the subject of considerable research and speculation, notably in poet Rita Dove’s book “Sonata Mulattica.” In 2015 the violinist Jennifer Koh asked me to write a companion piece to the “Kreutzer” sonata. My response was “Bridgetower Fantasy,” a collection of musical imaginings about George Bridgetower.

From our 21st-century vantage, considering Bridgetower’s unique circumstance, we can only see him as an ambiguous figure who, in embodying difference, provoked inspiration, fantasy, desire, anger, and finally, erasure. When reflecting on the greatness of a figure like Beethoven, I find it helpful to remind myself how much of music’s history lies deep beneath its surface — and particularly how many great music-makers barely left a trace in the archive.

Chaya Czernowin

Walter Bigelow Rosen Professor of Music

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

If composers are allowed to contribute to the flow of the music stream through their voices, Beethoven has imagined and was able to intervene and change the riverbed. In his middle period we can hear modernity, which can never become conventional: We hear the premonition of the conventional and its subversion in action. This is a live testimony for modernity because both are there, the convention and its subversion, the act of intervening for the sake of reexamination or finding a new path is asserted as something tangible, a kind of an essence of modernity which can be always experienced, regardless of style.

However I am truly fascinated with Beethoven’s late period. There all dialectics have melted away and ceased to exist. The intense and conflicting emotions comprising the fabric of the music interweave into a new transparent fabric of unified reflection. This fabric is so different from the fabric of dialectic of the middle period: In Beethoven’s late period he reaches a gaze, which has left the rebelliousness and anger behind and originates in a bird view of emotionality and behavior, which is sublime and abstract. At times one is unsure whether this is acceptance or total dissolution or delirium, whether this is utmost spirituality where one maintains a belief learned through emotional strain or a descent into the deepest crevices of the bodily existence and delirium. As unfathomable as it is, it seems to me to be both. The constant seismographic micromovements, which draw a path or a continuum between acceptance to dissolution or delirium makes the authenticity of this gaze even stronger and deeply touching for me.

This gaze is strange. It is at the same time universal and truly singular. At its base there is a foreign element, which is like a diamond of expression which is not breakable, never diluted or possible to explain and with which I remain forever fascinated.

Veronica Leahy ’23

Courtesy of Veronica Leahy

From all accounts, Beethoven was not only a great composer but also a legendary improviser. His famous improvisation duel with Daniel Steibelt was almost like the equivalent of a modern-day jam session. Something to note about this duel was that Beethoven did not fabricate an entire new sonic world on the fly; rather, he embellished upon the first few measures of the sheet music that Steibelt dramatically threw to the ground. His ability to embellish on themes and organically develop motifs is apparent throughout his entire catalog and is what has had the greatest impact on me as a composer and, perhaps even more, as an improviser. Sometimes the most compelling pieces or solos, regardless of genre, consist of taking a simple rhythm or a small sequence of notes and repeatedly turning it on its head. Beethoven could imagine the same melody from many different perspectives, which is quite remarkable considering that he could not literally hear them. Take his Fifth Symphony, which we all know and love. He could twist around those four notes in such compelling ways that, nearly two and half centuries later, we still feels its resonance and ingenuity. Beethoven’s music can be connected with on both a highly intellectual and intuitive level, forcing both the mind and body to respond intensely.