Photo illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

Reining in growing powers of the presidency

Two White House vets say experience with President Trump highlights need for long-overdue curbs

Both Republicans and Democrats have voiced concerns over the past few decades about the expansion of presidential powers — some of it ceded by Congress looking for political cover, much of it a result of White House legal interpretations of constitutional gray areas. The balance of power now tilts in favor of the Oval Office, but since President Richard Nixon leaders have held themselves largely in check, respecting long-established informal rules and norms.

Then came President Trump. A self-described rule breaker, he has ignored tradition and standards of presidential decorum and tested the limits of the office, violating traditions, norms, and even laws, according to many legal scholars. The Constitution provides two tools intended to keep recalcitrant presidents in line: impeachment and reelection. But as the past four years — including these weeks before President-elect Joseph Biden’s inauguration on Jan. 20 — have demonstrated, these correctives do not always work as intended. And they won’t curb a president who may regularly act in problematic, but not illegal, fashion.

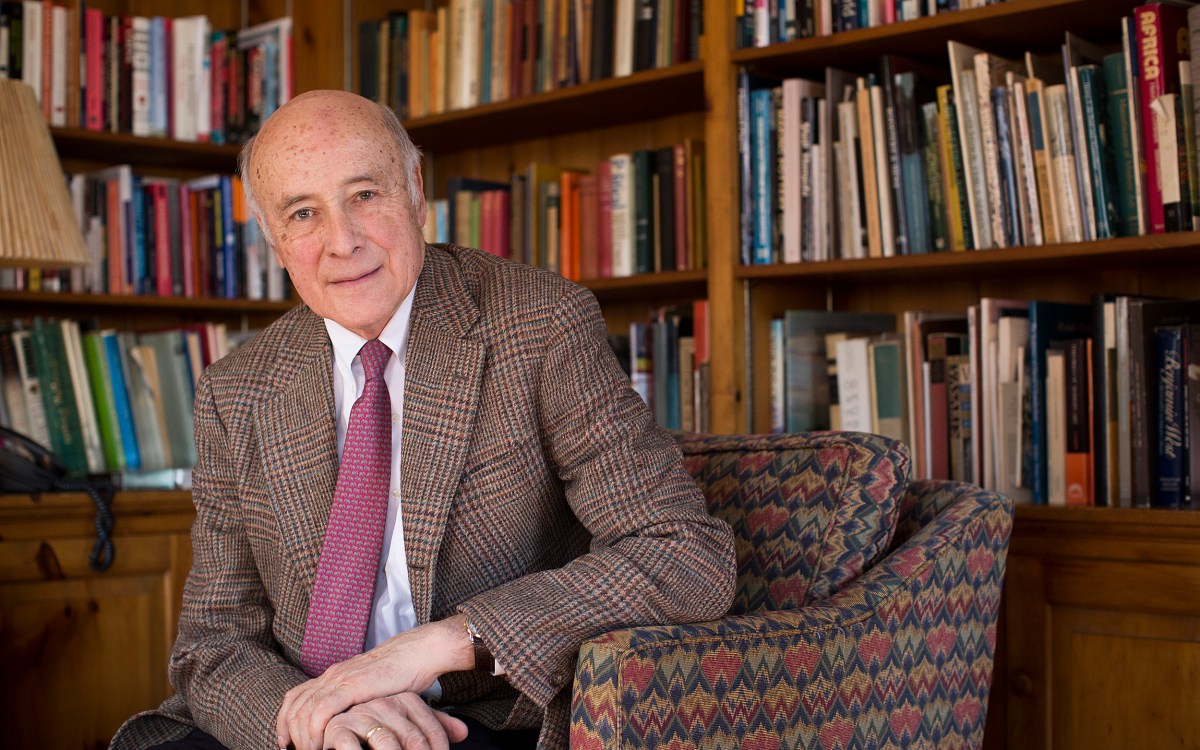

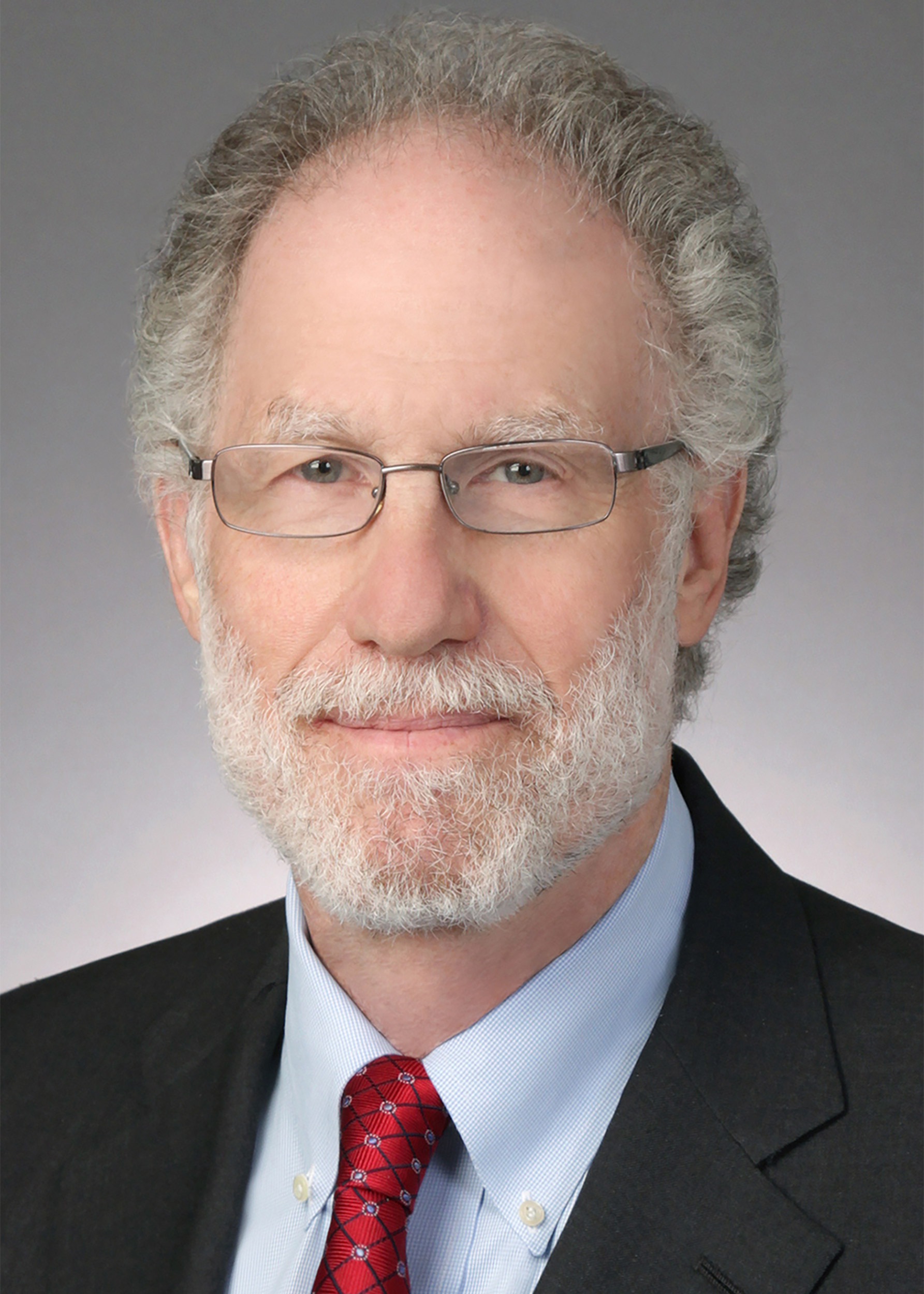

In a new book, “After Trump: Reconstructing the Presidency,” attorneys Bob Bauer ’73 and Jack L. Goldsmith, veterans of Democratic and Republican White Houses, respectively, propose what they say are long-overdue reforms to the Office of the President that can rein in future presidents who try to exploit the position for their political or personal benefit.

Goldsmith, Learned Hand Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, served as assistant attorney general in the Office of Legal Counsel during the George W. Bush administration. He writes frequently about national security, government, and politics, and is a founding editor of Lawfare. Bauer, a longtime legal adviser to President Barack Obama who is now advising the Biden campaign, is widely regarded as a leading authority on executive branch powers. He served as White House counsel from 2008 to 2011 and is now a professor of the practice and distinguished scholar in residence at NYU Law.

Q&A

Bob Bauer and Jack L. Goldsmith

GAZETTE: Plenty of presidents have pushed the outer limits of executive branch power for their own political gain. Is Trump the only reason we need to “reconstruct the presidency”?

GOLDSMITH: There were norm violations and legal concerns before Trump. But in almost every one of these areas, [he] has acted in ways that make all of the problems that were on the radar screen before much, much, much worse. Trump has exposed a lot of ways of exploiting the presidency and skirting norms and skirting laws that we worry a future president can exploit.

Norms are principles of right action that are not backed by legal enforcement but rather are part of the culture of the executive branch. They’ve worked remarkably well since Watergate. A lot of the post-Watergate reforms were about instantiating norms in the executive branch to deal with problems, some of which can’t be regulated by law. Because the president under Article II of the Constitution controls the executive branch, for example, it’s very hard to have a legally independent entity examine the presidency. You have to do that through norms and internal regulations.

But some norms can and should be changed into enforceable laws. In the past, we had presidential tax disclosure and compliance with conflict of interest norms — everybody agreed that the president would abide by them. There was no need to have a law. Every president since Watergate abided by these norms. But if there’s a president who is shameless and wants to accept the political cost, they can be violated. Trump has done that over and over again in a number of ways that should never be allowed to happen again.

We believe in a strong presidency. We’re not trying to fundamentally diminish the office. A strong presidency is necessary in the dangerous and very complex world we live in and that’s why the presidency, over time, has gained so much power. But the question is whether the president is adequately accountable to law, to the public, and to the Congress. Those things have to go hand in hand if you’re going to have a strong presidency. It has to be adequately constrained.

GAZETTE: Given the partisanship in Washington, are there some areas ripe for reform that both sides are most likely to agree on?

BAUER: It does seem to us that there are basic issues around which a bipartisan consensus might be possible: Presidents should produce their tax returns, and we need more controls on financial conflict of interest. Every reform is going to require, some more than others, some balancing of interests where the objective is meaningful reform without damage to the president’s legitimate personal rights or constitutional role.

It seems quite simple to require the president (and vice president) to disclose their taxes. But how will the requirement be structured? What happens if he or she refuses to do it? What rights does Congress have to obtain them if the president won’t comply? What about the IRS audits of every president’s tax returns, which are conducted as a matter of IRS policy since the 1970s? Why shouldn’t the public see the results of those audits?

Under our proposal, the president would be compelled to produce his or her tax returns through the same statute that requires presidents to file a global picture of his or her financial interests: the Ethics in Government Act. The act would be amended to require the April 15 release of returns, with no extensions granted. All presidents have managed to comply with the April 15 deadline and that would be the expectation under this reform. And we would extend the tax disclosure requirement to members of the president’s family who occupy senior positions in the government. Trump has installed his son-in-law and his daughter in the West Wing: Their tax returns ought to be disclosed. And then, remedies for enforcement should be available. Congress could provide that the secretary of the Treasury produce the returns if the president doesn’t supply them as required by the law to the Office of Government Ethics for review of completeness and for public release. If the secretary of Treasury fails to do so, Congress should be specifically authorized to obtain relief in federal court.

GOLDSMITH: The devil is in the details. It’s not enough to say, “The president should disclose his tax returns.” You need to fit that into extant law and the extant obligations. You have to think about questions like, “What if he wants to get a delay? Is he allowed to?” The answer must be no. You have to worry about enforcement. It was really important to us to get down into those details because those details matter, frankly, if these reforms are going to work.

Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith.

Courtesy of Lawfare Institute

GAZETTE: President Trump has directed the FBI and the Department of Justice to pursue his perceived enemies, including former President Obama and President-elect Biden, and urged federal prosecutions and sentences against his friends be soft-pedaled or dropped outright. He has also shared top-secret intelligence about national security with Russia and journalist Bob Woodward, which only he is permitted to do. Given the wide latitude presidents have over national security, intelligence, federal law enforcement, especially the DOJ, how can we ensure this power isn’t abused?

GOLDSMITH: It’s very hard. How you guarantee independence and integrity of law enforcement by the Justice Department that is under the control of the president of the United States is one of the great challenges of American constitutional law. We don’t think there are any easy solutions. You just mentioned the president ordering the attorney general to investigate and to prosecute his opponents. Trump has been pushing that since the first week he’s been in office. People don’t appreciate this: [former U.S. Attorney General] Jeff Sessions and now, William Barr have not, in fact, done that. So I would say that Trump has actually been ineffective in getting his Justice Department officials to prosecute his enemies. In part, that is attributable to Trump’s incompetence, but it should give at least some comfort.

But the Justice Department has not always appeared to resist Trump’s pressure. Attorney General Barr has been criticized for carrying the president’s water on [former National Security Adviser Michael] Flynn, trying to abrogate that conviction and the Roger Stone sentencing recommendation.

Barr also broke norms in connection with his choice of John Durham, the U.S. attorney from Connecticut, to conduct an investigation of the investigation of the Trump campaign. There is an argument to be made for looking thoroughly at that investigation so there could be lessons learned for the country. But the way that that investigation has developed seems illegitimate to us. We don’t think that should be the job of a U.S. attorney. Th[at] should be done by an inspector general, not a criminal investigator.

Also, and this is very bad in our judgment, Attorney General Barr has, for almost two years, prejudged publicly that investigation. He’s commented on it incessantly. The attorney general has delegitimated that investigation by having a running public commentary on it, which is contrary to Justice Department norms. The problem is that the regulations don’t explicitly apply to the attorney general. We would make very clear that the attorney general, absent very special circumstances, shouldn’t be doing that. Finally, if an inspector general does uncover criminal wrongdoing by a prior administration, it’s very important that investigation be done by a special counsel with some independence for the appearance and reality of fairness.

“It turns out that it has been very difficult for Donald Trump to enlarge his core base of support precisely because there is still in the American electorate an attachment to democratic norms, and we can build on that.”

Bob Bauer

GAZETTE: We’ve never had one president try to criminally prosecute another, whether warranted or not. Should that be permissible?

GOLDSMITH: There are two opinions in the Justice Department, one from the Nixon administration, one from the Clinton administration, that say the president cannot be prosecuted while in office. What that means is that when a president does wrongdoing in office, he can be impeached or the evidence can be collected. Those opinions make clear that it’s allowed in theory for the president of the United States to be prosecuted after he leaves office for crimes committed in office.

My basic view is, in the right circumstances, it’s perfectly legitimate to investigate and prosecute a former president for crimes committed in office. I argue, on pragmatic grounds, that it would be a mistake to do so in Trump’s case. (There are some ongoing investigations of Trump right now. Those should continue because they don’t concern actions that he took in office.) What I’m concerned about is having a new administration investigate and prosecute the prior administration for crimes committed in office — not as a universal rule, but in this context.

- It is not at all clear what crimes he committed. The most likely is obstruction of justice, which is a very difficult crime to prosecute under the current set of obstruction statutes. So it’s not at all clear that that investigation would be fruitful in reaching prosecution.

- We’re in a very dangerous situation now where we’ve already had two rounds of criminal investigations.

First, we had the Obama administration investigating the Trump campaign and then the Trump transition, and then it became the Trump administration. Whatever you think of that investigation, right, wrong, or otherwise, it was hugely controversial to have one administration investigating criminally another administration’s campaign [and] transition. That is something that 40 some-odd percent of the country are really upset about. Second, you have Barr doing an investigation of those investigators through the lens of criminal law. And then we’re talking about having the next administration do an examination of Trump through the lens of criminal law. I think it’s a terrible precedent to set, and it’s establishing a pathway for how we deal with disagreements and prior administrations. In a democracy, that is a very fraught path to go down. It would consume the next administration. It’s going to make it very hard for the Justice Department to try to restore belief in objectivity in the rule of law when it’s going after what many will deem [are] political enemies.

The argument on the other side, which I get, is: “The rule of law will be damaged if he committed crimes [and] you don’t go after him because it means that the president got away with it.” That’s a cost to what I’m proposing. But we have to take into account the possibility that they’ll fail just like the impeachment failed. There are many ways of having accountability besides political prosecutions. It’s really not about politics. It’s about the many costs, political and normative, and healing.

BAUER: I take issue with the position we may have maneuvered ourselves into. And that is, on the one hand, we have executive branch law that immunizes the president from prosecution while he or she is in office. And on the other hand, we have at least the emergence of a norm that counsels against prosecution once he or she has left office, in the name of national unity and healing. This is the legacy of Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon. It concerns me a great deal. All of Jack’s concerns are entirely valid. But it is critical that we not backslide from the overriding principle that a president is not above, but is accountable under, the law.

This can be done through the adoption of rigorous process, coupled with transparency. … I recognize, and I think everybody does, that not only could the investigation and prosecution of an ex-president consume the country, but a former reality TV star like Donald Trump, particularly an aggrieved one, could seize upon and revel in his role as victim. He will argue that it is all an extension of the “witch hunt” against him from the moment it appeared that he might be elected in 2016 all the way through the impeachment process in 2020 and beyond. But we pay a price for the rule of law and withstanding this demagoguery is one such price. We shouldn’t subscribe to the proposition that presidents have that much leverage over us — that their ability to disrupt the political process in their own interest will be rewarded by effectively conferring upon them lifetime legal immunity.

Moreover, if we cannot accept that the federal government may proceed in some disciplined and principled way to investigate, and if warranted prosecute, the actions of a past president, this may simply push this pursuit of legal accountability to the state and local level. District attorneys and state attorneys general may be under pressure to try in helter-skelter fashion to uphold the rule of law because federal authorities won’t act. I don’t know that that’s terribly helpful, and it may exacerbate the fear that the prosecutions are political “witch hunts.”

GAZETTE: Can anything be undertaken right away under a new administration?

GOLDSMITH: About half the reforms in the book can be implemented by the attorney general and the president very early on in the next administration. Almost all of the special counsel reforms can be done by the attorney general just issuing new regulations. Some of the Justice Department independence proposals can be implemented by the attorney general. The idea that the Durham investigation is not the right approach, that can be changed by regulation and set down a new norm for those kinds of prosecutions. There are reforms we haven’t talked about, some problems in the way the FBI and Department of Justice investigated both the Hillary Clinton email investigation and aspects of the Trump campaign. We think it’s very important for there to be guidance about the allocation of authority between the Justice Department and the FBI about when and under what circumstances and by whose order presidents and presidential campaigns should be investigated. All of that can be implemented by the next administration. It will depend upon what the president and what the attorney general think are important.

On the statutory front, the norm of tax disclosure, the norm of avoiding presidential conflict of interest was widely accepted by both parties and pretty well followed for 45 years before Trump came into office. We think once Trump is out of office, the low-hanging fruit can be implemented very quickly. Some of the things get more politically contested. There’s already a bill that instantiates our pardon reform. It seems like there should be bipartisan support in Congress for that. Other stuff, like [executive branch] vacancies reform and war powers reform, that’s going to be very hard because that implicates traditional separation of powers disputes between the branches.

GAZETTE: What can ordinary citizens do?

BAUER: There’s no question that tolerance for norm-shattering is often rooted in the perception that institutions have failed to deliver on basic commitments, and further, that the norms protect the elites and allow for corrupt governance without accountability. So we’re going to have to confront and address this concern that all the talk about institutions and norms is meaningless, a cover for institutions that help those on the inside and don’t deliver for people on the outside.

It is important that as a consequence of this election and in the years ahead, that individual officeholders be called to account for their behavior on these issues. We have to hope for an exchange between the electorate and elected officials that rewards and reinforces the defense of institutions and honoring of norms and punishes behavior that is destructive to institutions and devalues norms. If we have that, those norms are going to make a comeback, along with everything Jack and I have suggested in the way of statutory and regulatory support of this revival. It turns out that it has been very difficult for Donald Trump to enlarge his core base of support precisely because there is still in the American electorate an attachment to democratic norms, and we can build on that.

Interview was lightly edited for clarity and length.