Rain and mud in WWI battlefields have long been chronicled. In August 1917, a team of stretcher bearers struggle through deep mud to carry a wounded man to safety during the Battle of Boesinghe in Belgium.

Creative Commons/Public Domain

Six-year deluge linked to Spanish flu, World War I deaths

Study offers clues to how weather affected world’s deadliest disease outbreak

A new collaborative study by a group of scientists and historians finds a connection between the Spanish flu’s European outbreaks, including its most deadly one at the end of World War I, and a six-year period of atrocious weather taking place at the time, which blew in cold temperatures and torrential rain from the North Atlantic.

The findings by a team led by Alexander More, a research associate in the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard, combines ice-core data from a European glacier with epidemiological and historical records, as well asinstrumental readings in order to map temperature, precipitation, and mortality levels from what they term a “once-in-a-century climate anomaly.” They find the most miserable weather overlapped or just preceded peaks in Spanish flu mortality. The crests also coincide with some of the war’s most notable battles in the years before the flu’s arrival — the Somme, Verdun, Gallipoli. Historical accounts of those actions detail bloody warring between combatants additionally plagued by frostbite, water-filled trenches, and unending mud.

More, who is also an associate professor of environmental health at Long Island University and an assistant research professor at the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute, said though many other factors doubtless played roles in the outbreak’s deadliness — not least the virus’ natural virulence in a population whose immune systems had never seen it before — the unusual environmental conditions likely also played a role, causing crop failures, physically stressing millions of men living in precarious conditions, and potentially interrupting migratory patterns of waterfowl that are known to carry the disease.

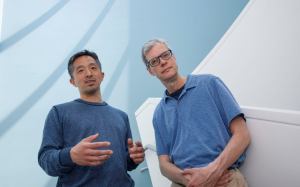

Alex More, research associate in the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard, who led the study.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

While the rain and mud of the battlefields have been heavily chronicled, “the thing that we didn’t know was what anomaly caused that,” More said. “We also didn’t know how that anomaly functioned, that it was a six-year anomaly. We didn’t know the close pattern between the precipitation record and the pandemic. Basically, we saw a spike in cold, wet marine air from the northwest Atlantic that came down into Europe and lingered.”

The work was published in the journal GeoHealth and supported by a grant from Arcadia, a charitable foundation of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. It came about through a collaboration between researchers at Harvard, the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute, the University of Nottingham — including archaeologist and historian Christopher Loveluck — and Long Island University. The findings are the latest to stem from an ongoing partnership between Harvard’s Initiative for the Science of the Human Past and the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute. The project pairs Harvard historians and University of Maine climate scientists who’ve drilled and analyzed a 72-meter ice core from the Colle Gnifetti glacier on the Swiss/Italian border.

“The fact of the matter is that the ice core has been full of surprises … when we applied for the grant we did not expect to shed light on the flu pandemic of 1918 and weather conditions in the trenches of World War I,” said Michael McCormick, Harvard’s Francis Goelet Professor of Medieval History, chair of the Initiative on the Science of the Human Past, and a senior author on the paper. “With the ice core — over 100 years — you can see what you can’t with the historical record, that this was an extraordinary anomaly.”

Senior author Michael McCormick.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Climate Change Institute Director Paul Mayewski, another senior author, said their analysis included chemical proxies for 60 different variables and is able to detect changes in the ice column that relate to specific storms. The most meaningful find was elevated concentrations of sodium and chloride — a marker of the anomaly’s origin in the salty waters of the North Atlantic — between 1914 and 1919 that were unmatched in 100 years.

Mayewski said an important factor in enabling the findings was the central European location of the glacier from which the core was taken.

“The closer the ice core is to the action, the more relevant it is,” Mayewski said. “I think the most interesting thing [is] that, in a bad sense, a perfect storm occurs. … In this particular case it was the combination of a pandemic and climate change and we all know that that’s exactly what’s happening right now. In the case of World War I, the people who were impacted by this — up to 500 million — were even less likely to get through it because of all the stresses that were already in existence, everything from the battlefield to malnutrition.”

“The environment is a complex system. We can’t account for all variables of how climate affects the outbreak of disease, but we know for a fact that it does.”

Alex More

Historical accounts of conditions at the front commonly mention torrential rains that filled trenches with water, keeping troops continually soaked, and creating seas of churned mud that swallowed, horses, machines, even men. More cited poet Mary Borden, a war nurse and suffragette, who after The Somme wrote “The Song of the Mud,” in which she refers to themuck as “the vast liquid grave of our armies” whose “monstrous, distended belly reeks with the undigested dead.”

The study picked up three peaks of heavy rains followed by spikes in mortality in 1915 and 1916, which led to crop failures and hardship during what was called the “turnip winter” in Germany. The final leap in 1918 preceded the Spanish flu’s most deadly wave in autumn as the war was drawing to a close.

Though debate remains over the Spanish flu’s origins, there seems little doubt about the deadly impact of waves that began in the spring of 1918 and its connection to wartime troop movements. Though estimates vary, it is thought to have infected 500 million and killed 30 million to 50 million.

“The environment is a complex system,” More said. “We can’t account for all variables of how climate affects the outbreak of disease, but we know for a fact that it does.”