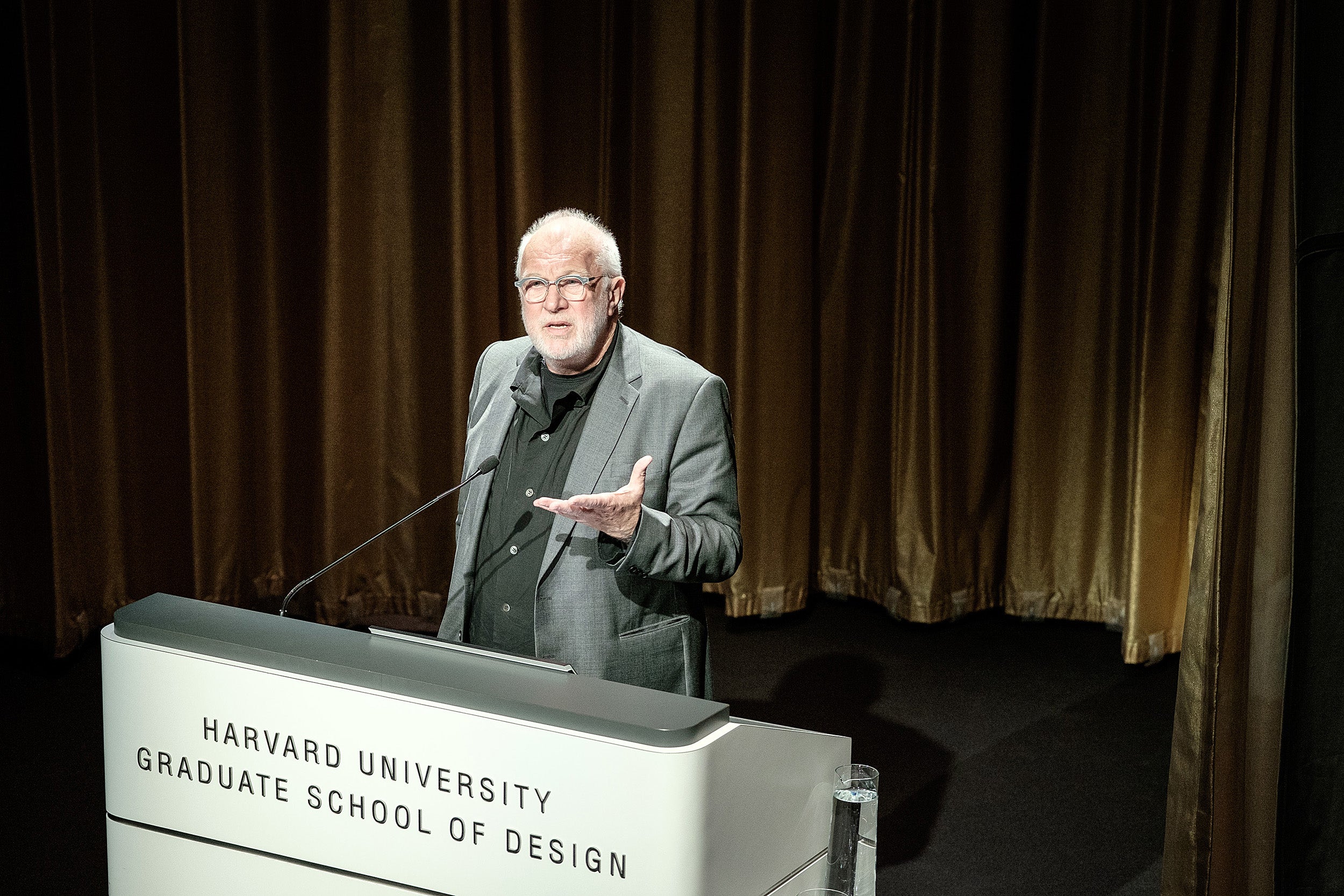

“We are not changing to solve a problem with the program. We’re changing to expand the influence of the program,” said K. Michael Hays, program director and Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory.

Courtesy of Graduate School of Design

Graduate School of Design revises master’s program

Curriculum aims to encourage multidisciplinary studies, real-world results

Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) today announced a substantial revision of its Master in Design Studies (M.Des.) program. The new curriculum is designed to encourage multidisciplinary study and to address the changing real-world needs for design.

The new program replaces former eight concentration areas with four “domains,” all designed to address the interaction of design with landscape, ecology, infrastructure, and other environmental concerns. The domains are: ecologies, which explores the connection of design with landscape and infrastructure; mediums, taking up innovative design methods to engage the public and social realms; narratives, centered around the social, technical, cultural, and political contexts of design; and publics, focusing of the relationship between the built environment and its surroundings. More than a dozen possible “trajectories” will be offered across any of the domains for greater flexibility, allowing students to design his or her own program.

“We are not changing to solve a problem with the program. We’re changing to expand the influence of the program,” K. Michael Hays, program director and Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory, said this week. “When this program started in the ’80s we had four subject areas, which exactly mapped the curriculum. It was very efficient and solid, but very boring.

“Over the past 10 years we’ve built up areas that were more topical — art in the public domain, what we call critical conservation, risk, and resilience. These address concerns which don’t fall strictly within the profession but can be addressed by collaborative design practices. This has made the program successful. It draws students who have a background in design but want to work outside and across the limits of their profession.”

Hays said this heightened desire for a curriculum that was more urgent and useful inspired the decision to widen the lens. “The need for further expansion came directly from a concern about the climate, given the past government administration’s rollback of regulations and denial of climate change. This was something we thought design could and should address. The Black Lives Matter movement also had very direct impact on our curriculum. Students rightly demanded more courses that address issues of social equity in spatial terms. Also, there are various ways design could address racial and gender equity. These events directly impacted our curriculum and we felt like we needed to add more areas.”

The idea that the curriculum should be linked to larger social issues has grown over time. “That’s a philosophy or attitude that has developed. I don’t think it was solely the product of a change of deanship or a change of administration,” Hays said, referring to Sarah Whiting’s installation as dean last year, following the 11-year tenure of Mohsen Mostafavi.

“The Black Lives Matter movement also had very direct impact on our curriculum. Students rightly demanded more courses that address issues of social equity in spatial terms.”

K. Michael Hays, GSD

“It was something that affected faculty and students alike, as the world has changed in terms of recognition of different human groups and communities of individuals who are making new kinds of social demands,” he said. “For instance, you might say ‘I don’t want to get training to be a corporate architect. I want to design products or even software that will solve different kinds of problems.’ That would be one case for change. Another is the very idea that climate change is driven by human activity — which would mean that you can intervene in it. The general recognition is that you can intervene in things that were thought to be unchangeable and that design could make those changes.”

As an example of this philosophy in action, Hays cited the work of Professor Krzysztof Wodiczko, particularly a celebrated video installation that his students created in 2015, when the John Harvard Statue in Harvard Yard was made to appear to speak to students about the history of race and design. “This was something unique — not a painting, not a sculpture, but highly sophisticated digital technology used for social activism.”

He envisions a further blending of disciplines in the future. One example might be to integrate design with public health, creating areas that are conducive to hiking or biking. Another would be linking design with surrounding landscapes.

The program, Hays says, encourages innovation on the students’ part. “The student we expect to get already has a bachelor’s degree and maybe a master’s in a related field — a student who has some life experience after college. This kind of student would enter into one of the domains when they get here and start learning more about the curriculum and the offerings. The domain gives you the foundation; the trajectory is where you launch from it. For a student there is the flexibility of any graduate program, but also the choice of where you want to be. Do you want to walk away with an understanding of digital technology and its applications, or knowledge of ecological science?”

The program, he says, also benefits from other departments’ willingness to make resources available to GSD students. “We owe something to the department chairs and directors, who in a way have to agree that they will make these courses available to people who are not actually in their department. So there has been an enormous amount of goodwill.”