Jordan “Trey Deuce” was featured in Rudy Hypolite’s documentary, “This Ain’t Normal.” Jordan, who scored high on his SATs, had to drop out of school and go to work at a young age.

Photos courtesy of Rudy Hypolite

His hobby? Making award-winning documentaries

Longtime AV staffer chronicles inner-city lives in his spare time

Rudy Hypolite is known among faculty in the Science Center as the go-to guy who records lectures and provides multimedia support for their courses.

“He’s delightful and endlessly helpful,” said Professor Dan Lieberman. “I had no idea he was a filmmaker.”

Indeed, the Trinidad-born Hypolite has been making documentary films for much of his adult life. His latest work, “This Ain’t Normal,” which was released in June to North American audiences, tells the story of young men involved in Boston gangs and the efforts to help them get the support they need to transform.

“I grew up with gangs in Academy Homes, a low-income housing complex in Roxbury. You never on the news saw their backstories. It was just always negative,” said Hypolite, who spent two years following five young men around with digital cameras and his Kreateabuzz production team, including co-producer Dennis G. Wilson.

transcript

Transcript:

Rudy Hypolite: It was important to me to tell this story through film of young men involved in gang activity because when I looked on the news, all I saw was the violence and the negative. So for me as a filmmaker, I wanted to see if I could get to the backstories of these young men or the youth advocates who work with them. Because in growing up in Academy Homes in Roxbury, I grew up around a lot of young men who later became involved in gangs. And so I saw them in a very different light. They were my friends, they had dreams and aspirations like anyone else. So I wanted to see if I could get to that story and allow them to share their life experiences and what led them to the gangs.

Hypolite has always kept his filmmaking separate from his work at Harvard, where he has been employed for 24 years. He takes time off in the summer for filming and edits at night and on weekends during the winter months.

“Funding is tough,” he said. “Sometimes it’s out of pocket, or on the credit card. Lately it’s grants. But I’ve established myself as someone who can get things completed. We have an incredible team.”

“This Ain’t Normal” was a natural progression of storytelling for Hypolite, who produced “PUSH: Madison vs. Madison” in 2012. “PUSH” told the poignant story of a troubled basketball team at Madison Park Technical Vocational High School that was a state championship contender, and their head coach and teacher, Wilson, who is trying to hold the whole thing together. The dramatic 2011 season, set against a backdrop of grinding poverty, family instability, and gun violence, won the Roxbury Film Festival award for best documentary and showed at the New York International Latino Film Festival.

The success of “PUSH” — it played on ESPN Classic and PBS World Channel for three years — gave Hypolite affirmation that audiences wanted to see and hear from voices in ignored and neglected communities, which he had heard himself as a 14-year-old immigrant who began English High School in Boston in 1974, when desegregation was just beginning.

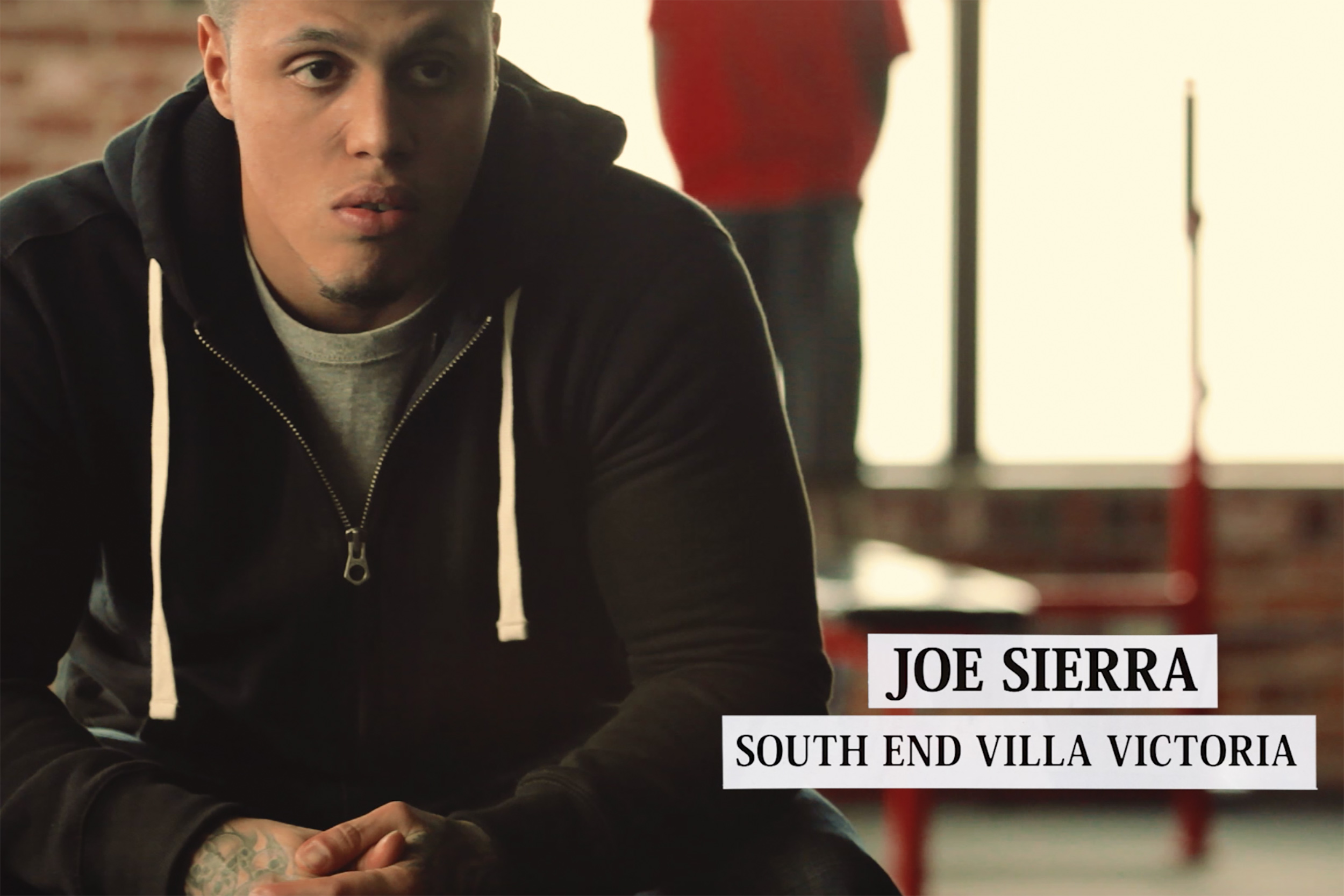

Some of the people featured in Hypolite’s film.

“It’s been a theme of my work to show the resiliency of a people, the resourcefulness of a people even given those types of institutional challenges.”

Rudy Hypolite

“Coming to Boston was a shock to me. School was pandemonium, and there were lots of fights between Blacks and whites. We would see on the news how young people of color were treated by white adults in South and East Boston,” he said.

That Hypolite would eventually become a filmmaker seems nearly inevitable in many ways. His great-uncle, E.R. Braithwaite, had written “To Sir With Love,” the autobiographical novel that was the inspiration for the 1967 hit movie of the same name starring Sidney Poitier. Hypolite’s own passion for filmmaking was fueled watching Henry Hampton’s documentary series “Eyes on the Prize,” which premiered in 1987 and concluded in 1990. Still, as the first in his immediate family to attend college, he found life in his first year as a commuter student at Boston University “tough.”

“The level of writing and analysis — I don’t think I was up to par. I had to work hard at night to keep up. In most classes I was the only person of color, but I wanted to show I belonged,” he said.

After graduation, he joined Cambridge Community Television, an innovative environment in which he produced work that won an American Film Institute award for excellence in local television programs. But he wanted to try TV directing and moved to Los Angeles to work in post-production on “The Big Easy,” a USA Network show.

“By that time I had a spouse and two daughters, and my family stayed here. I was working six days a week, 15 hours a day, and I couldn’t see doing my own productions. After a couple of years, I came back and reestablished myself to do documentary filmmaking,” he said.

transcript

Transcript:

Rudy Hypolite: Growing up in the low-income black neighborhood of Roxbury, I feel I’ve definitely benefited from the richness of those experiences, which are reflected in my films. For example, growing up in this close-knit neighborhood, where all families knew and looked out for each other and witnessing the resourcefulness and resilience of these families, and then having friends who later became involved in gangs, was my motivation for wanting to dig deeper into the backstories resulting in this current film, This Ain’t Normal. My prior film, Push: Madison Versus Madison, about the inequities and challenges of an inner city high school basketball team, may have been connected to my attending high school in Boston, during the desegregation of the schools and busing of students and the racial turmoil I saw firsthand and on the nightly news.

One of my earlier films, Moving Up, dealt with the migration of young Black women from the Deep South to cities like Boston, New York, Chicago, in search of a better life as domestics, and then being exploited, which as I reflect back is directly related to my own family’s migration from Trinidad to Boston in search of more opportunities, and my father’s experiences as an undocumented worker. So those and other life experiences, really informed the type of person I am and the films I choose to make about the people who live in Boston. We’re currently working on a film on the experiences and atmosphere of black barbershops and hair salons. Our film company, Kreateabuzz Films, positions itself as black Boston on film. And I now realize there’s a reason why our films have such a national broadcast appeal. Boston really is a microcosm of the nation, and I’ve found that these subjects and experiences on film, are relatable and resonate in other parts of the country.

He returned in 1996, joining the AV Department at Harvard to direct and produce documentary videos on campus life, research, and faculty and alumni profiles. He continued to work on his own documentaries on his own time. In 2010, he moved to the Science Center, joining the multimedia team as supervisor supporting FAS Sciences and Gen Ed high-profile lecture classes.

His first documentary was about young Black women who had migrated from the South to work as domestics and had been exploited.

“I have seen systemic racism — people who from growing up have not been able to realize their full potential,” Hypolite said. “It’s been a theme of my work to show the resiliency of a people, the resourcefulness of a people even given those types of institutional challenges.”

For “This Ain’t Normal,” Hypolite, who now lives in Stoughton, intended to document a front-line worker at StreetSafe Boston, an antiviolence nonprofit that works with youth and young adults. But, once embedded in the organization, he found the young male gang members eager to tell their stories.

“No one wants to know their story, not even their family members,” he said. “These young men were able to speak to what had transpired in their young lives. Jordan ‘Trey Deuce’ from St. Joseph’s [Crew], who has a young daughter” — Jordan tells the camera that he’s both a great father and a terrible one — “spoke so eloquently and exhibited a high level of intelligence about so many subjects, about how many people lost their lives in different cities, his anger, and his own internal battle between knowing the importance of education and liking having a reputation. He had no father in his life, his mom [was] a crack addict. He scored high on his SATs but had to drop out and work at an early age. I saw that in each of these young men.”

transcript

Transcript:

Rudy Hypolite: I’ve worked in different aspects of filmmaking, but I love documentary filmmaking because you get a chance to craft a story from real life. And I’m inquisitive by nature, so I get a chance to learn about people, learn about a subject. And in my approach, there are so many stories that can be told. I try to choose stories and give voice to those who normally would not have a chance to talk about themselves or their experiences. So, if I’m able to get the right access and the trust of those folks, then I know I can get to the core of their story, so that’s wonderful. And then, the collaborative nature of the process, you’re working with others, you’re working with a production crew, you’re working with an editor, you’re working with a composer, so there’s that aspect of it, the collaborative aspect, that is terrific.

And the final piece is some of the soundbites you get that people say, I always chuckle to myself and say, “If you’re a writer and you’re creating something for an actor, there is no way you can come up with that.” So, it’s a real privilege and I love doing it.

Hypolite depicts StreetSafe worker Leroy Peeples as a kind of Sisyphus-like character, facing a task both necessary and seemingly destined to fail.

“What I do isn’t a job,” he says. “I have to make sure this kid doesn’t get killed. What is that!?”

Hypolite spent months editing the 200 hours of footage with his production team, but he said having it debut at a moment of racial reckoning in this country has been powerful.

“George Floyd just opened things up to a conversation people weren’t willing to have, and everything in this film speaks to that. I feel like it will contribute to the conversations we need to have,” he said. “The feedback we were getting humanizes these young men, and when that officer’s knee was on Mr. Floyd, he treated him as subhuman. If we want to make a change, we need to provide equitable services to have productive citizens who will contribute.”

“This Ain’t Normal” is available to rent or purchase on several video streaming services.