Emily Balskus, professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Harvard University and co-senior author of the recent study.

Photo by Sophie Park

Microbes might manage your cholesterol

Researchers discover mysterious bacteria that break it down in the gut

There are fewer stars illuminating the universe than there are bacteria in the world. Many species are known, like E. coli, but many more, sometimes referred to as “microbial dark matter,” remain elusive. “We know it’s there,” said Doug Kenny, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Chemistry in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, “because of how it affects things around it.” Kenny is co-first author on a new study in Cell Host and Microbe that illuminates a bit of that dark matter: a species of gut bacteria that can affect cholesterol levels in humans.

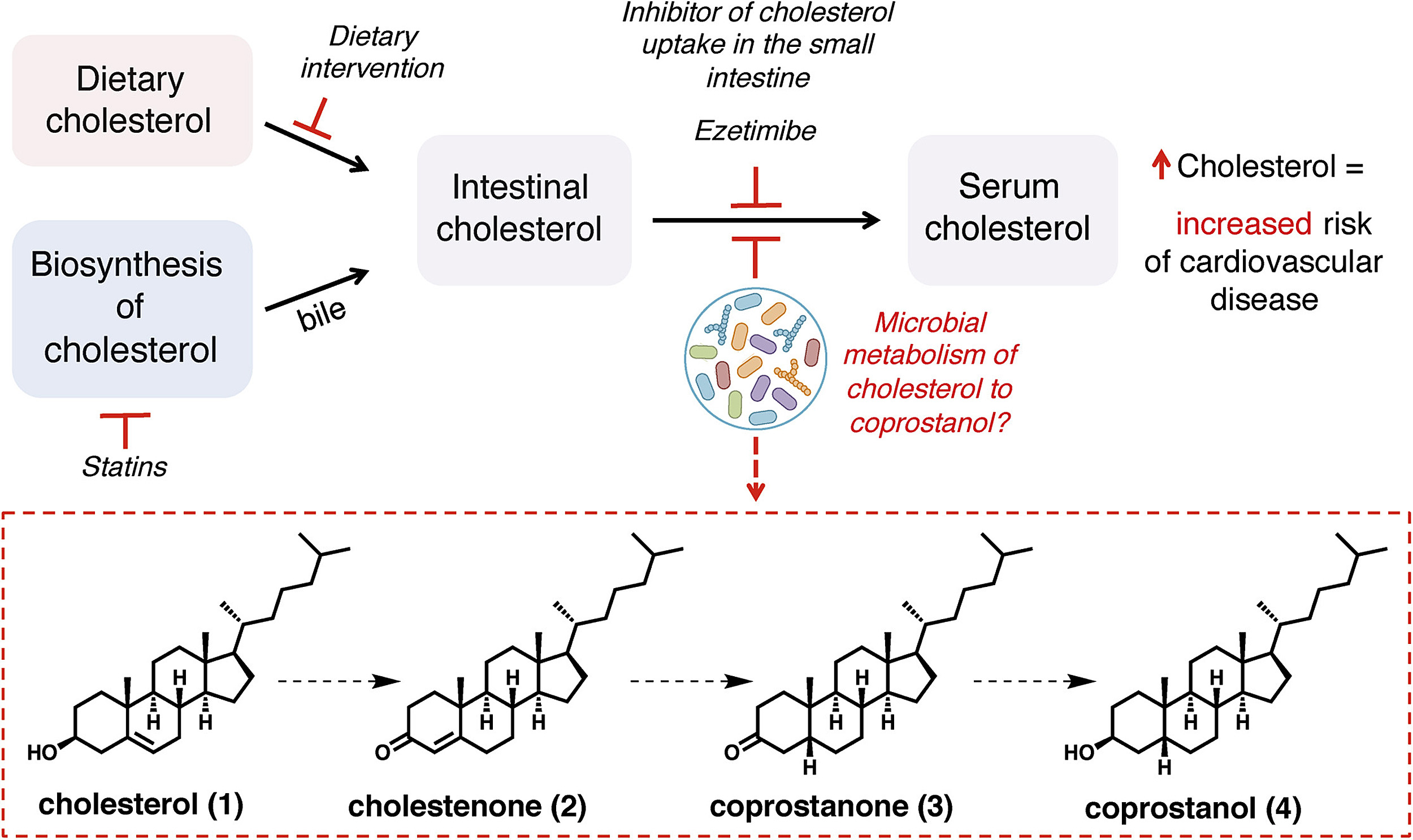

“The metabolism of cholesterol by these microbes may play an important role in reducing both intestinal and blood serum cholesterol concentrations, directly impacting human health,” said Emily Balskus, professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Harvard University and co-senior author with Ramnik Xavier, core member at the Broad Institute, co-director of the Center for Informatics and Therapeutics at MIT, and investigator at Massachusetts General Hospital. The newly discovered bacteria could one day help people manage their cholesterol levels through diet, probiotics, or novel treatments based on individual microbiomes.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2016, more than 12 percent of adults in the U.S. age 20 and older had high cholesterol levels, a risk factor for the country’s No. 1 cause of death: heart disease. Only half of that group take medications like statins to manage their cholesterol levels. While such drugs are a valuable tool, they don’t work for all patients and, though rare, can have concerning side effects.

“We’re not looking for the silver bullet to solve cardiovascular disease,” Kenny said, “but there’s this other organ, the microbiome, another system at play that could be regulating cholesterol levels that we haven’t thought about yet.”

Since the late 1800s, scientists have known something happens to cholesterol in the gut. Over decades, work inched closer to an answer. One study even found evidence of cholesterol-consuming bacteria living in a hog sewage lagoon. But those microbes preferred to live in hogs, not humans.

Prior studies are like a case file of clues. One huge clue is coprostanol, the byproduct of cholesterol metabolism in the gut. “Because the hog sewage lagoon microbe also formed coprostanol, we decided to identify the genes responsible for this activity, hoping we might find similar genes in the human gut,” Balskus said.

Meanwhile, Damian Plichta, a computational scientist at the Broad Institute and co-first author with Kenny, searched for clues in human data sets. Hundreds of species of bacteria, viruses, and fungi that live in the human gut have yet to be isolated and described, he said. But so-called metagenomics can help researchers bypass a step: Instead of locating a species of bacteria first and then figuring out what it can do, they can analyze the wealth of genetic material found in human microbiomes to determine what capabilities those genes encode.

Plichta cross-referenced massive microbiome genome data with human stool samples to find which genes corresponded with high levels of coprostanol. “From this massive amount of correlations, we zoomed in on a few potentially interesting genes that we could then follow up on,” he said. Balskus and Kenny sequenced the entire genome of the cholesterol-consuming hog bacterium, mining the data and discovering similar genes: a signal that they were getting closer.

Kenny then narrowed their search further. In the lab, he inserted each potential gene into bacteria and tested which made enzymes break down cholesterol into coprostanol. Eventually, he found the best candidate, which the team named the Intestinal Steroid Metabolism A (IsmA) gene.

“We could now correlate the presence or absence of potential bacteria that have these enzymes with blood cholesterol levels collected from the same individuals,” said Xavier. Using human microbiome data sets from China, the Netherlands, and the U.S., they discovered that people who carry the IsmA gene in their microbiomes had 55 to 75 percent less cholesterol in their stool than those without.

“Those who have this enzyme activity basically have lower cholesterol,” Xavier said.

The discovery, Xavier said, could lead to new therapeutics — like a “biotic cocktail” or direct enzyme delivery to the gut — to help people manage their blood cholesterol levels. But there’s a lot of work to do first: The team may have identified the crucial enzyme, but they still need to isolate the microbe responsible. They need to prove not just correlation but causation — that the microbe and its enzyme are directly responsible for lowering cholesterol in humans. And they need to analyze what effect coprostanol, the reaction byproduct, has on human health.

“It doesn’t mean that we’re going to have answers tomorrow, but we have an outline of how to go about it,” Xavier said.