The Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology’s curatorial staff had resources ready well before the coronavirus hit.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Though museums are closed, the work continues

Staffs using the time to update and build out databases for use by researchers now and in the future

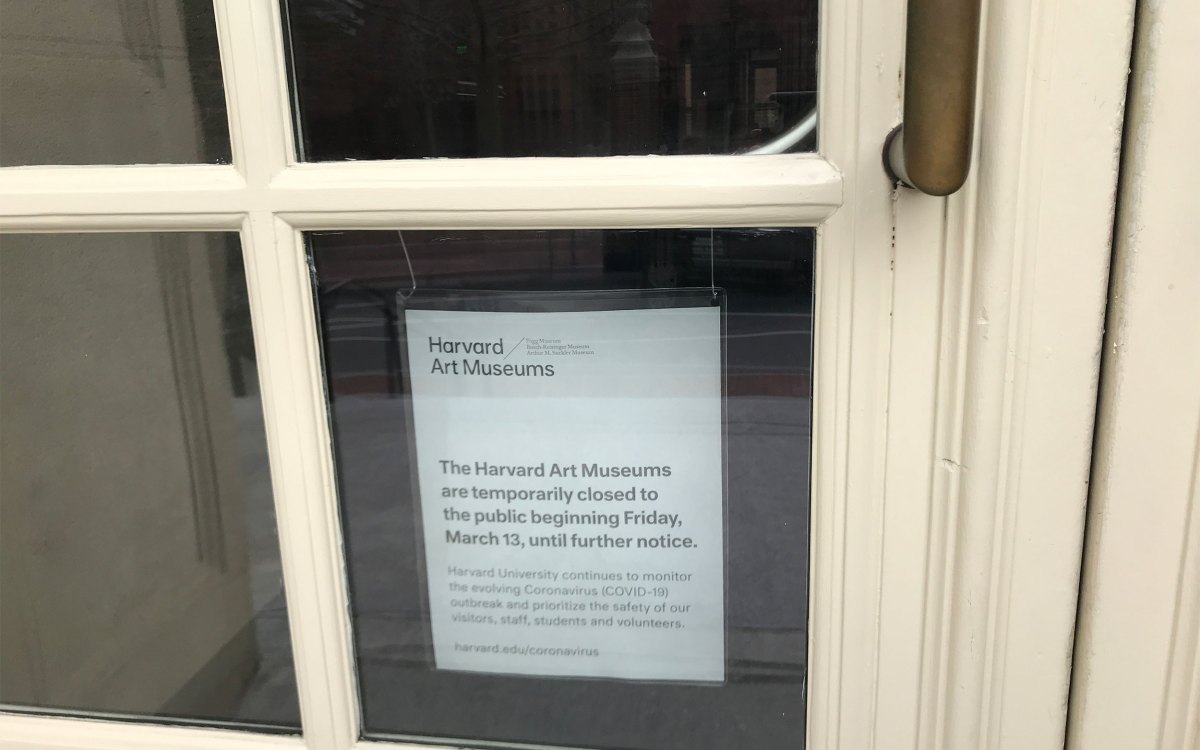

In the days since the pandemic sent Harvard’s museums online, many have been sharing their offerings with the public through virtual tours, talks, and gallery displays.

But behind the scenes, staff members across the network have pivoted from their normal duties in curation, collections management, and conservation to the enormous task of updating, adding, and editing data for millions of items housed in University collections, efforts that will prove invaluable for those doing research in them.

“This is where the work that’s been going on for so many years to digitize museum collections and records is really paying off,” said Jane Pickering, William and Muriel Seabury Howells Director of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography, noting that the Peabody and other institutions such as the Harvard Art Museums and the Harvard Museum of the Near East have recorded lectures, conducted digital programming, and made images of artifacts available to the public for years.

At the Peabody, staff sprang into action from home to expand and refine the museum’s digital database of records for 750,000 artifacts. Almost half of the 50-member team trained to work on the project, called Remote Access Data Verification and jointly run by the collections management and curatorial teams.

The group has been working to build out the information, including geographical and contextual data, on items from Panama, objects created by indigenous artists and makers in North America and Oceania, and a European archaeological collection excavated by Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Germany.

The initiative will be particularly helpful for researchers who may not have access to physical museum resources for months. One example is the detailed and corrected evidence of object histories that enables researchers to connect them to an original source, a process that would have required on-site access.

Despite the change in focus, some tasks continued unabated after the evacuation of campus, including faculty support and resources for courses and student research.

From her home in Hyde Park, N.Y., history and literature concentrator and museum student worker Keziah Clarke ’20 kept up her research assignments for Museum Curator of Visual Anthropology Ilisa Barbash for the forthcoming book “To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes,” co-published by the Peabody Museum Press and Aperture, and a planned complementary exhibition.

“It’s really interesting work looking at photography and the interconnecting areas of art and science and racism in America,” said Clarke. “Working has helped me stay focused, and I’m really grateful to be able to work during this time.”

“These resources are already up and running and available for people who want them, even though they were created well before we ever expected that we would need to use them in this manner.”

James Hanken, Director of Museum of Comparative Zoology

To prepare for a long period of working from home, curatorial staff at the Museum of Comparative Zoology brought home as many paper files on the museum’s zoological specimens as they could, and began to input and update information in MCZbase, the museum’s extensive digital database of records for around 10 million specimens — about half of the total number of objects in the collection.

The database includes images, geographical and species information, and 3D models. The museum is also in the midst of a larger initiative to link its information to other collections databases around the world.

“These resources are already up and running and available for people who want them, even though they were created well before we ever expected that we would need to use them in this manner,” said James Hanken, director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, curator of herpetology, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology, and professor of biology.

Hanken noted that museum staff had to pause the process of taking 3D computed tomography scans of skeletons and images of specimens for the MCZbase while away from campus. But, he said, “Typically, only a portion of the workday for curatorial staff is spent attending to the database, but the campus evacuation has restricted the range of other things they can do, and as a result [this] is something they can focus on.”

The pause affected curators’ offered new opportunities to reimagine pedagogical practices using the online offerings.

“On the one hand, this has hit us hard because we can’t physically access the specimens we use in research and teaching. On the other hand, because so many of our past activities have emphasized digital data and digital representations of these specimens, conversely we’ve been able to successfully make this transition,” said Hanken. “I won’t say it’s painless, but we have the materials already available that allow us to continue our scholarship and our teaching.”

Pickering noted that many of the staff members are working outside of their areas of expertise to continue to educate and support scholarship.

“I think it’s a really great example of staff coming together and thinking about what it means to be in this new situation, [and] to continue the critical work of the museum even when we’re not in the building,” she said. “It’s been a really wonderful thing to see. People think of our shuttered institutions, but the museum work continues.”

Programming staff at The Harvard Museums of Science and Culture, which comprises the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East, Harvard Museum of Natural History, and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, utilized the resources of six different Harvard collections and, in April, launched HMSC Connects!, an initiative that expands online educational activities.

In addition to existing online resources such as exhibit videos and tours, and live-streamed and recorded lectures, the team launched “HMSC Connects! Families,” an email newsletter of museum resources to help children and parents with at-home activities focused on nature and culture, including language mini-lessons, a seed sprouting tutorial, and a weekly Nature Story Time session. They also started the HMSC Connects! Podcast, a weekly behind-the-scenes look at the research and collections at the museums, and an Instagram-based Explorer’s Club, and planned a digital version of the popular Solstice events held in June ever year.

“What this [situation] has forced us to do is look more broadly and deeply at how we can still connect with our audience and build upon what we’ve already been doing in a much more thoughtful way,” said Janis Sacco, director of exhibitions at HMSC. “We’re engaged and feeling like we’re building something together and creating something we can all be proud of. I think it will make us a stronger institution.”

Jeff Steward, director of digital infrastructure and emerging technology at the Harvard Art Museums, praised his staff for adapting quickly to changes in their workflow and tasks after moving online. Like their colleagues across the campus museums, the staff turned their attention to building out online stores of information for the roughly 250,000 objects in the museum’s collection.

“We were in a good place because over the past 10 years or more we had put so much effort into being ‘digital first,’” said Steward. “Our staff is largely mobile to begin with, and we’re in this moment where our data is being enriched by more people on our staff than I could have ever imagined.”

After training on data entry cataloging standards with collections information and database specialist Kathleen Kennelly, each staff member started researching his or her assigned pieces and adding biographical and contextual information using an internal database system accessible only to museum staff. The information is used to populate a different, public collections database on the HAM website, where visitors can read biographical and acquisition information about pieces on display and in storage at the museum. The information refreshes daily and links to other resources like the Getty Union List of Artist Names database.

“A collections database, in the best situations, can be used as the single source of truth for information about a collection,” said Steward. “This is a highly collaborative and distributive effort, and it’s a big undertaking for any museum to build a catalog” that incorporates art historical scholarship, conservation information, and proper visual descriptions for scholarly and accessible use.