Illustration by Elena Mozhviolo

Spirituality, social justice, and climate change meet at the crossroads

Divinity School’s Dan McKanan talks about Earth Day’s evolution

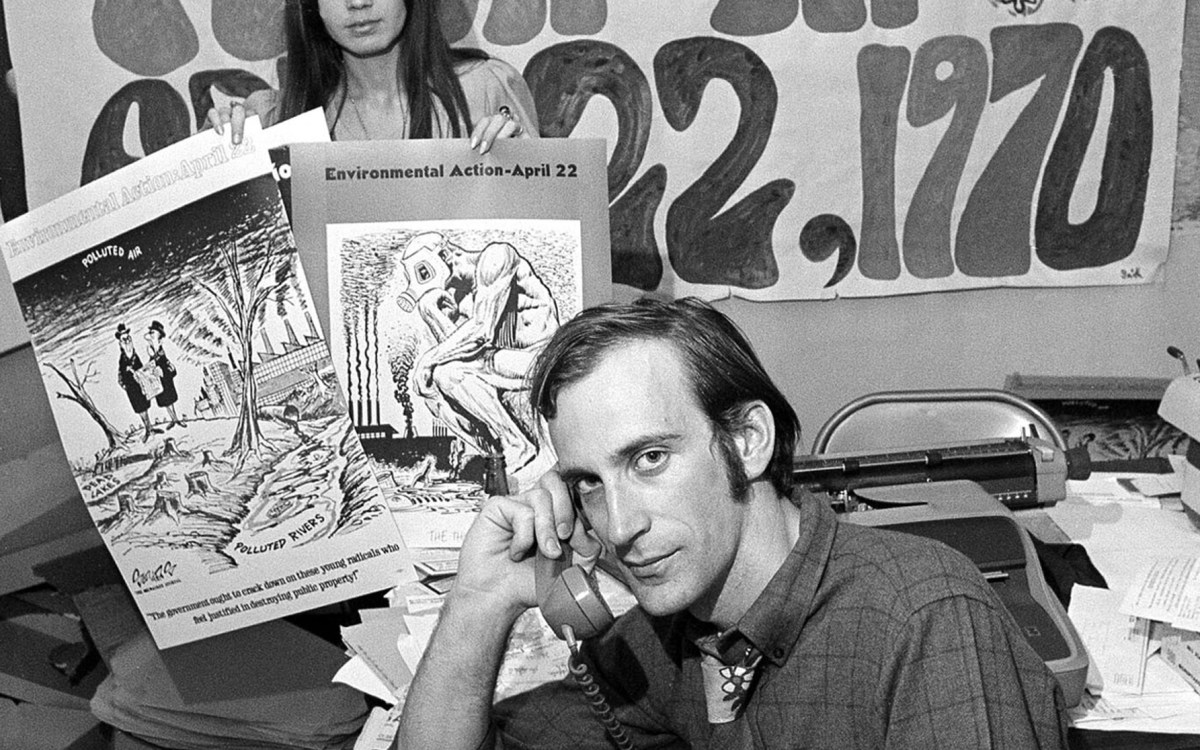

On April 22, 1970, millions of people in the United States took part in demonstrations and rallies in streets, parks, auditoriums, and college campuses to call for a healthy, sustainable environment and to decry its deterioration. That first Earth Day launched the modern environmental movement.

To understand how the movement has evolved 50 years later, Harvard Divinity School (HDS) spoke with Dan McKanan, Ralph Waldo Emerson Unitarian Universalist Association Senior Lecturer in Divinity and director of the new Program for the Evolution of Spirituality at HDS.

McKanan discusses the ways in which spirituality interacts with climate change, how religious communities are developing new rituals and practices to support climate activists for the long haul, and how religious organizations have ensured environmentalism includes social justice.

Q&A

Dan McKanan

HDS: Can you briefly describe the current ways in which spirituality interacts with climate change, and vice versa?

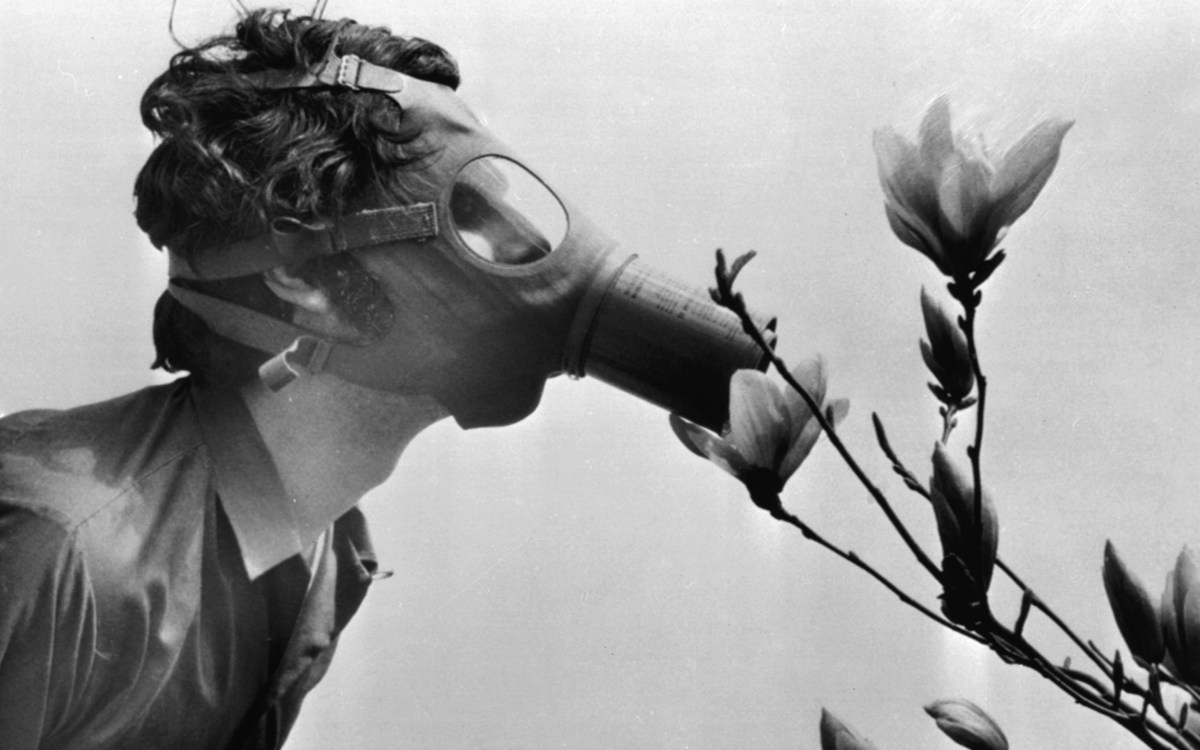

McKanan: Climate change is a global phenomenon that touches every aspect of human experience, and so it is no surprise that spiritual practices are changing as a result. More and more people seek spiritual disciplines that remind us of the continuity between humanity and the rest of nature. These disciplines include tending a garden, following a long-distance hiking trail, “forest bathing” in an urban park, and even climate activism itself. Many people are finding new meaning in ancient dietary laws, which they now recognize as strategies for honoring the more than human life forms on whom we depend. And rituals of mourning and lament are increasingly important, as we recognize that many species and many human communities will suffer irreparable damage.

HDS: The description for your course “Introduction to Religion and Ecology,” says that “‘Religion and ecology’ is one of the fastest-growing subfields within the study of religion.” Why is that?

McKanan: I am sure there are many reasons, but I will highlight three. First, climate change, biodiversity loss, and the disproportionate impact of environmental problems on the poor and marginalized constitute an urgent moral crisis that demands the attention of religious ethicists and public leaders within all faith traditions. Second, these challenges are global in scope and are impacting all religious traditions simultaneously. This creates unprecedented opportunities for the comparative study of how religions respond to new challenges. Third, ecology is itself a powerful method of study. The practice of attending to interconnections and the ways in which the whole may be more than the sum of its parts is relevant not only for the study of biological systems, but also for the study of cultural systems that are themselves fully immersed in biology.

HDS: What are some ways religious communities are taking climate action? How are they uniquely positioned to do so?

McKanan: Globally, religious denominations have led the way in divesting endowments from fossil fuels, accounting for 30 percent of all endowments that have divested. (University endowments, by contrast, account for only 15 percent.) Denominations can also model ways to hold environmentally sustainable conventions. In recent years, for example, the Unitarian Universalist Association has partnered with the convention centers that host its General Assembly to establish or expand composting, recycling, and local purchasing programs. Locally, religious congregations are present in every community and thus are perfectly situated to model good environmental citizenship. When congregations install solar panels, plant gardens, or serve as pick-up-sites for community supported agriculture, they make these practices accessible to millions of people.

HDS: How does social justice fit into the intersection of spirituality and climate change?

McKanan: Probably the most important way that religious organizations — especially ecumenical Christian and Jewish organizations — have influenced environmentalism is by insisting that the well-being of ecosystems can never be separated from the well-being of human communities. The concept of “environmental racism” — which names the ways in which pollution and other negative environmental impacts are concentrated in communities of color — was introduced by the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice in the 1980s, building on a local campaign to stop the dumping of toxic waste near a majority-black community in North Carolina. This was possible because Christian churches had a long tradition of fighting against racism, dating to well before the first Earth Day in 1970.

HDS: Bad news stories seem to outnumber good news reports related to the environment. More species becoming extinct, massive loss of forest land, global average temperature inching higher, and other irreversible damage done to the planet by humans. What can individuals do to not be overwhelmed by these reports and to continue to take climate action? What spiritual resources are there for environmental activism?

McKanan: Countless traditions, congregations, and movements are developing new rituals and practices to support climate activists for the long haul. One thing they have in common is an awareness that we are never alone when we work to save the planet. As is evident from the rebirth of forests in the eastern United States, ecosystems have the capacity to heal themselves with just a little help from humanity — and in so doing they provide human activists with spaces for reconnection and spiritual practice. And most environmental organizations are themselves communities of mutual support, where people look out for one another as well as for the planet. If you are involved in an environmental organization that does not enhance your personal connection to people and nature, please look for another!

HDS: In 2020, you launched the Program for the Evolution of Spirituality at Harvard Divinity School. The program supports the scholarly study of emerging spiritual movements, marginalized spiritualities, and the innovative edges of established religious traditions. What topics or themes will this program explore in relation to the study of religion and ecology? How do you hope this program informs students’ and participants’ understanding of climate change, climate action, and environmental activism?

McKanan: The anonymous donor who endowed the Program for the Evolution of Spirituality wanted HDS to support both scholarship about emerging spiritualities and leadership within emerging spiritual communities. So we plan a series of thematic conferences that will connect scholars and leaders to one another, as well as to critics who highlight the ethical abuses of many spiritual communities. We’ve chosen ecology as the first theme because of its potential to highlight connections among diverse spiritual paths. We had hoped to host a mini-conference on “Emerging Spiritual Practices for a Wounded Planet” in May 2020. That has been postponed to next year due to coronavirus, and we are now seeking proposals for our spring 2021 conference on “Ecological Spiritualities.” Please see the program’s website for details and updates.

HDS: This year marks the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. What’s your view of how the movement has evolved over the last half century? Do you have any plans to mark this occasion?

McKanan: The first Earth Day accomplished three things. It expanded public awareness of environmental concerns, unified the diverse strands of the environmental movement, and aligned environmentalism with a set of social justice movements generally regarded as “progressive” or “leftist”: socialism, anti-racism, feminism, and queer liberation. Before 1970, by contrast, wilderness preservation was often separate from organic agriculture, and both were as likely to make political alliances on the right as on the left. Since 1970, public awareness has continued to expand, albeit in fits and starts, and the leftist alliances are as strong as ever, evident in proposals for a Green New Deal that would address wealth inequality and ecological imbalance simultaneously.

I will confess that the coronavirus pandemic has drawn my own attention away from Earth Day 2020. But the global response to the pandemic has given environmentalists a powerful new tool. We now know that humanity is willing to suspend business as usual, even to risk our prosperity, when it becomes crystal clear that lives are at stake. The World Health Organization projects an annual loss of 250,000 human lives due to climate change, and one third of all species are also at risk in the next half century. Our challenge as environmentalists is to make these realities so evident that action will be unstoppable.