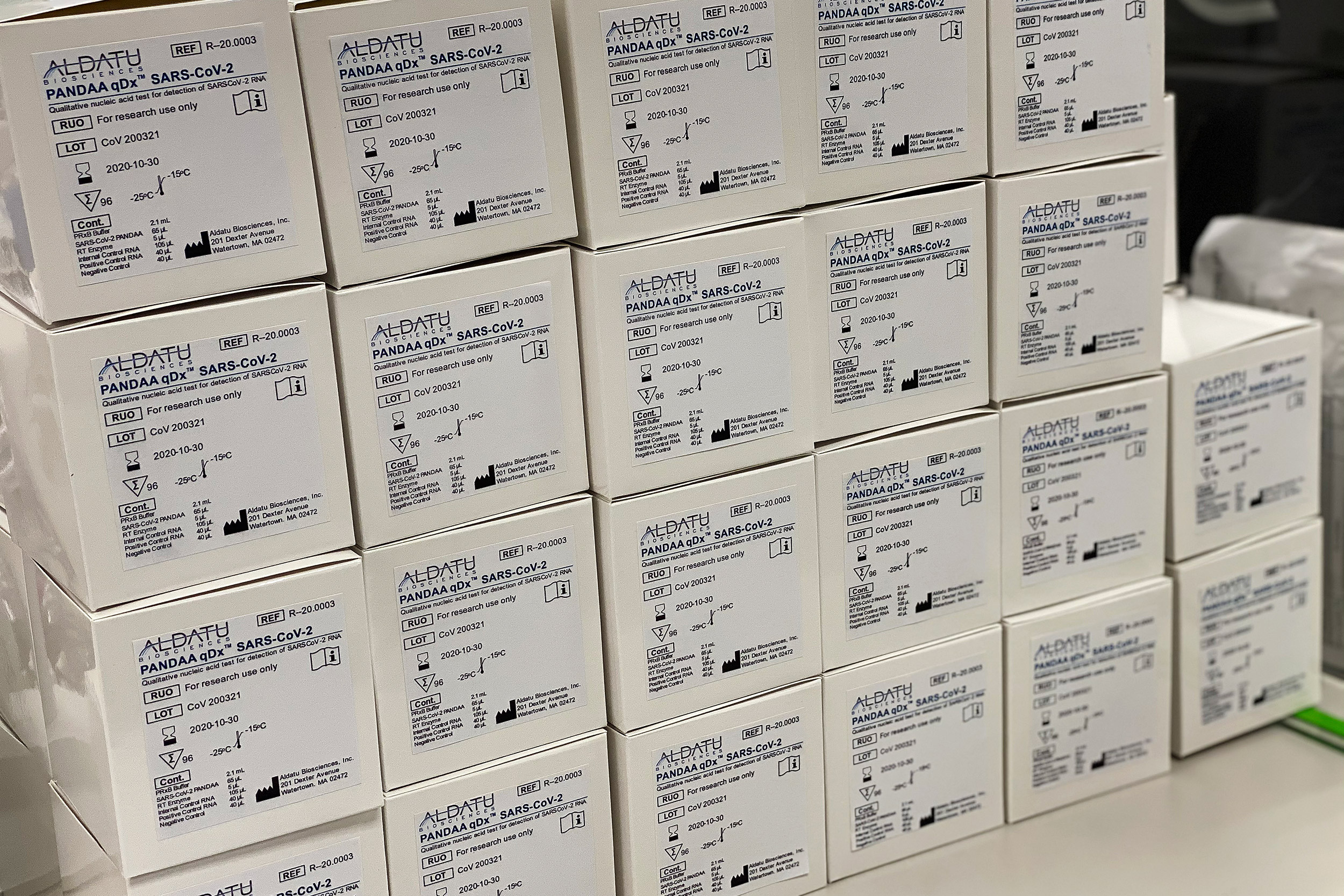

Aldatu Biosciences, a company born in Harvard’s Innovation Labs, helped the region ramp up COVID-19 testing.

Courtesy of Aldatu Bioscience

From the lab to COVID front lines

Technology developed at Harvard provides early boost to Mass. COVID testing

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

As Massachusetts rapidly ramps up COVID-19 testing, a technology born in the lab of Harvard AIDS pioneer Max Essex and nurtured by entrepreneurship resources on campus has played an important role in providing the needed reagents and kits that are driving a surge in testing.

At Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, which by Tuesday had conducted more than 3,000 tests, the first kits that fed the hospital’s rapid increase in diagnostic results since it started doing them in mid-March came from Watertown-based Aldatu Biosciences. [The Broad Institute also has made rapid, large advances in testing.] The nine-employee company was formed to commercialize this diagnostic technology developed at Harvard and was based at the Pagliuca Harvard Life Lab in Allston until January 2019.

Jeffrey Saffitz, chief of pathology at BIDMC and Mallinckrodt Professor of Pathology at Harvard Medical School, said the hospital’s lab has four high-volume testing machines, but had a shortage — as did other labs in the state — of the customized reagents needed to detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

While BIDMC awaited additional supplies from its regular commercial vendors, Aldatu worked with the hospital’s pathology staff to develop diagnostic kits and get them to the hospital. Saffitz said the rapid increase in COVID testing — as of Tuesday, they’d found 487 positives — was in part thanks to Aldatu’s nimbleness and to the efforts of hospital staff, including clinical microbiologists, laboratory technicians, lab managers, and others. By late last week, Saffitz said the hospital was ready to perform as many as 1,500 tests per day — an amount equal to an entire season’s worth of flu tests.

“Our machines were able to accommodate the Aldatu test kits. When this happened there was an incredibly effective partnership between our clinical microbiology teams and the Aldatu folks,” Saffitz said. “We worked together to advise them in terms of what they needed to do to make the test kits usable on our machinery. … We did all the validation studies of the test kit to prove that it actually worked, and it worked beautifully. And we were able to run the Aldatu test kits initially at a time before we had received test kits from the major supplier.”

Aldatu’s roots lie in Essex’s long-running Botswana-Harvard Partnership, established in 1996 to fight AIDS. In 2008, infectious diseases physician Christopher Rowley, then a research associate at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, was joined there by a postdoctoral fellow, Iain MacLeod. Rowley was working on HIV drug resistance, a continual problem in treating patients with antiretroviral drugs. Frustrated by the cumbersome existing process to determine whether a patient harbored resistant HIV strains, the two developed the PANDAA genotyping platform (Pan Degenerate Amplification and Adaptation), which provided rapid, low-cost HIV genotyping.

“Iain and Chris developed the PANDAA platform for PCR testing of drug resistance for HIV,” Essex said. “The goal was to develop a test that would be cheap enough for widespread use in low- and middle-income countries, where drug resistance testing was often not available.”

Rowley went on to a clinical post at BIDMC, where today he is an assistant professor of medicine and an infectious diseases physician, while MacLeod, interested in developing the technology further, went to Harvard’s Innovation Lab (i-lab).

Founded in 2011 as a way to support student entrepreneurs, the i-lab offers students working space, an entrepreneurial-minded community, and expert advice. At an i-lab workshop, MacLeod met David Raiser, a doctoral student in genetics and a technology assessment fellow at Harvard’s Office of Technology Development (OTD), where he was learning commercialization and marketing strategies for emerging innovations. The two first talked about PANDAA’s potential while waiting outside the i-lab for the shuttle to Harvard’s Longwood campus.

“David had an intuitive sense that this was a valuable technology with great potential to benefit the public,” said Grant Zimmermann, OTD’s managing director of business development, who worked with Raiser and MacLeod to set up Aldatu. “This was never just a money-making goal for David. He has a genuine desire to help people.”

The two created a business development strategy for Aldatu in 2014 and worked with Zimmermann to develop a license structure to support the company — a step that became official two years later.

“I’m immensely proud of the Aldatu team for being among the first to step up to make testing broadly available,” said Isaac Kohlberg, Harvard’s chief technology development officer and senior associate provost. “The ultimate impact of a new discovery may be difficult to fathom at the outset, but the Aldatu example shows why it’s so important to get promising technologies into the hands of passionate entrepreneurs who can advance and scale up an innovation for the public’s broadest benefit.”

In 2014, Aldatu received additional financial support in the form of the $40,000 Bertarelli Foundation Grand Prize in the Harvard Deans’ Health and Life Sciences Challenge. The team also won a $1.5 million small-business grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which let them begin full-time operation in 2015. The two moved to Kendall Square’s LabCentral in 2016, then returned to Allston to become an early tenant in Harvard’s Life Lab. In January 2019, the company moved into its own facility in Watertown.

“I’ve said for a few years now, Aldatu is a true i-lab story,” Raiser said. “We built very strong and meaningful and valuable relationships out of our time at the i-lab and the Life Lab.”

More like this

Aldatu was established as a public benefit corporation — which puts public benefit on a par with profits in the corporate mission — with the aim of providing easy-to-use, low-cost diagnostics for resource-poor areas.

They distributed tests for HIV in Botswana and developed a diagnostic for Lassa fever, another viral disease. In early March, as the lack of COVID-19 testing became acute, Rowley contacted MacLeod and asked whether PANDAA could be used for the disease. They developed the diagnostic in a matter of days and, by the time regulatory guidelines changed on March 16 to let private labs begin testing, they had already begun working with BIDMC to validate the test using blinded patient samples provided by the state.

“We had already, over the last six years, developed experience with assay development and applying that test development to infectious disease and working with viruses in outbreak concern areas,” Raiser said. “We were well-positioned to move quickly on the COVID-19 pandemic.”

A week later, Aldatu was not just providing kits to BIDMC, its officers were in conversation with other hospitals about doing the same and preparing to provide COVID-19 testing to partners in sub-Saharan Africa with whom they had been working.

“We’re trying to cast a wide net and fill gaps in testing access and capacity quickly wherever we can do so,” Raiser said.