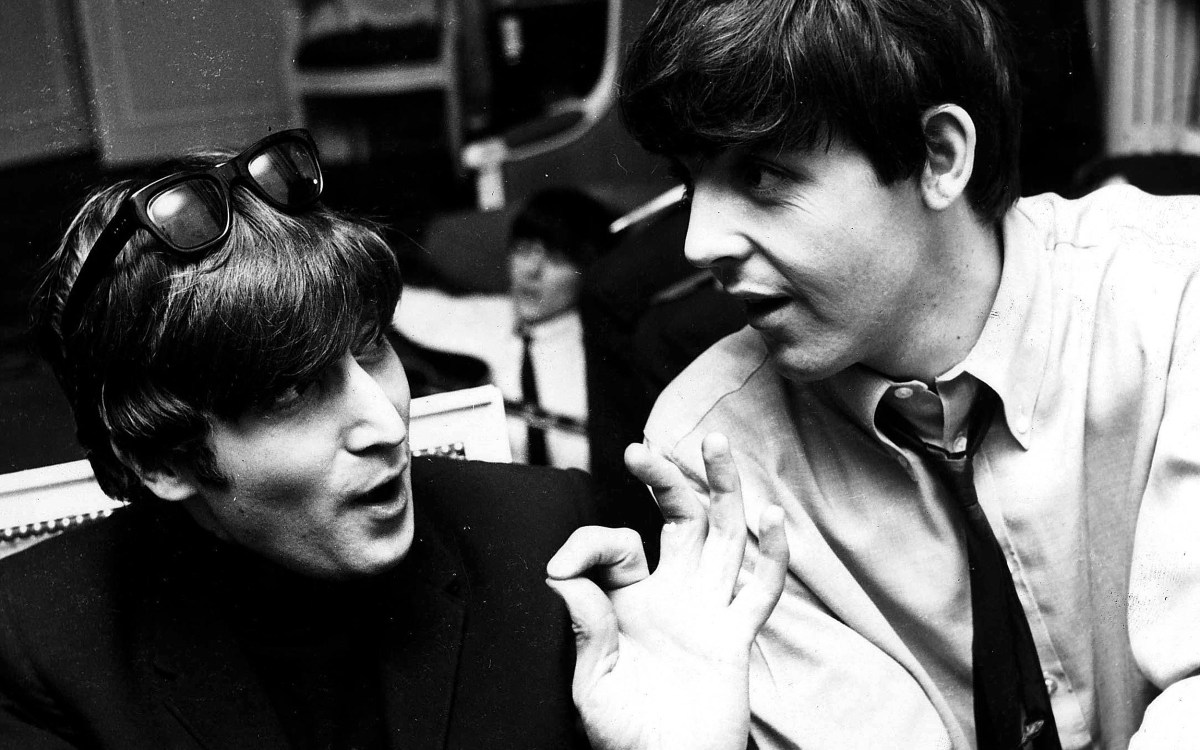

The Beatles were ahead of their time, embracing feminism as early as 1965, contends Beatles scholar Kenneth Womack.

Dan Gross/AP file photo

Baby, you can drive my car

The Beatles could be sexist jerks personally, but one scholar says the band surprisingly explored ‘proto-feminist’ themes in some songs

Looking back at your favorite classic rock songs through the lens of today’s attitudes about women’s empowerment, male privilege, and even sexual violence can be cringeworthy at best. But just as they were trailblazers in music, film, fashion, and popular culture, the Beatles were ahead of their time in embracing feminism, argues Kenneth Womack, a well-known authority on the band and dean at Monmouth University, evolving from early patronizing “hey, girl” entreaties to songs filled with independent women who don’t need a man, not even a Beatle. Ideological Diversity, a Harvard Kennedy School student organization, hosts a free talk with Womack on Thursday about how the group explored issues of feminism, gender, and inclusion in ways few rock bands dared in the 1960s. The event begins at 7 p.m. at Starr Auditorium and is open to the public. Here’s a primer on the talk ahead.

Q&A

Kenneth Womack

GAZETTE: The Beatles aren’t known for their ill treatment of women and certainly don’t have the reputation that the Rolling Stones did, who were notoriously sexist even by that era’s low standards. But I don’t know whether people think of them as “proto-feminists,” as you have referred to them. What do you mean by “proto-feminist” and in what way?

WOMACK: Rock ’n’ roll, or even popular music, [was] often highly gendered and sexist. It certainly was paternalistic in the ’60s and prior, in terms of songs being directed at women as objects, women as needing to be “counseled” about love, [or] it was about coming on to them, even if it was just something innocent and romantic, “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” And the Beatles very consciously in 1965 began to change their tone. They created a very specific type of female character who would think for herself and did not need a man. And that is revelatory, really. We have many songs that begin to appear at that point that are highly progressive about women living their own interests and aims and pleasure, as opposed to serving some undefinable other. It’s pretty exciting stuff. And it’s a great moment when I teach the Beatles because you can see the students picking up on what they were trying to do, and how unusual it was then, and perhaps even now.

GAZETTE: Women portrayed as something other than objects of desire or as saintly figures like “Lady Madonna” — in other words, as independent actors with agency?

WOMACK: Sure. “Ticket to Ride,” that’s a great example. Lady Madonna is not a saint; Lady Madonna is probably a prostitute. She has children, and they’re looking at Lady Madonna because society does not give a damn about her. The best thing she has is “listen to the music playing in her head.” The rest of it is: She has these children, which society wants her to do, but because of who she is and whatever her station is, she is a nonperson, a nonentity. And the saintliness, it’s an ironic comment on her position in life. She’s far from it. I mean, if anything, her closest cousin in the Beatles story is Eleanor Rigby, who’s good for picking up the rice in the church where the wedding has been.

GAZETTE: She’s an object of pity.

WOMACK: Oh, yeah. If you think about her at all, which you probably don’t.

GAZETTE: In which album does this woman character first emerge? Nineteen-sixty-five’s “Rubber Soul”?

WOMACK: We really start to see her appear on “Help!” Although you could make a case that she’s showing up even earlier on “Beatles for Sale,” where there’s a song called “No Reply,” which is fascinating because it is about a stalker who’s watching from across the street, sitting in some tree. He’s watching this woman, who has tried to make a decision to jettison him from her life. They’re really bringing up interesting questions about the place of women in these little romantic stories. You know, there’s a dark side to “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” [Laughs.] So there are a lot of songs, even these early songs, that are asking some pretty hard questions about the speaker. Sometimes they’re speaking ironically. Take “I’ll Follow the Sun,” which Paul wrote when he was 15 or something. That’s about a jerk who is going to be so emotionally immature that you’re not even going to know why he left or what happened to him. He’s gonna leave in the dead of night; one day you’re gonna wake up, and he’s gone. There’re several songs where they create these poses for these characters who are really terrible, even threatening.

GAZETTE: Indeed. “Norwegian Wood” is a lovely song, but it’s pretty horrific at the end. He’s basically angry that after a date with this independent woman, the night ended without sex so he burns her house down the next morning while she’s at work.

WOMACK: That’s right, but she’s still the winner. What he hated was the disempowerment.

“[The Beatles] were so influential … that they didn’t have to care about these kinds of things. They did them anyway because they felt they were important.”

GAZETTE: What prompted this shift in their portrayal of women? Clearly, some of it had to be the social circles they traveled in, the changing cultural attitudes all around them, perhaps their own maturation, but not all of their songs were autobiographical.

WOMACK: Many weren’t. They would sit down, and John and Paul would say, “Let’s bring her back for this song.” They didn’t call her a proto-feminist character, obviously, but they’d say, “Let’s bring her back. We’re doing ‘Drive My Car.’ Let’s make one a character here who — she’ll let you drive the car, but so what? You know, ‘Maybe, I’ll love you.’” There’s “Day Tripper,” so wonderful too in that same way. Got a “Ticket to Ride” too: She’ll go out with you but quit trying to tell her that you have to get married. Even the woman in “She’s Leaving Home,” although I don’t like the fact that to escape her parents and the constructedness of their lifestyle she has to meet with “a man from the motor trade.” But look, that’s John and Paul in 1967. That’s probably the best thing they could imagine 53 years ago! [Laughs.]

GAZETTE: Which Beatle led the way? Wasn’t John a notorious cad and admitted many years later that he had been abusive toward women in the ’60s?

WOMACK: “They” at this point is mostly McCartney. John Lennon lapses out pretty quickly in a bad marriage. It’s really being led by McCartney, who is suddenly reading and taking in culture in ways that he never had before, and so he would bring a lot of those kinds of ideas back. It also helped, painfully for him I guess at the time, but, living with the Ashers and [then-girlfriend] Jane [Asher] telling him that no, she doesn’t want to get married and put a ring on her finger. She’s an actress right now. She’s not going to stop touring … And he can stuff it. Paul reacts very badly to that. There are number of songs that are autobiographical where he comes off like a Class A jerk. In “We Can Work It Out” he’s not offering anything to work out! He’s saying, “Try to see it my way or we’re going to keep fighting.” “Things We Said Today”: My God, that’s an ugly, threatening song. “I’m Looking Through You.” Those were Jane songs. Even “For No One”: He doesn’t see love in her eyes anymore. She still loves him; it’s just not the love he thinks he deserves and should get. He may have been transitioning intellectually into a better space, but in his personal life, he wasn’t necessarily living it. Or John Lennon, the awful line about keeping women down and “getting better” that Lennon contributes [to “Getting Better,” which was written by McCartney].

GAZETTE: Neither sound especially feminist in their real lives. Why then did they pursue this proto-feminism in their songs? There was no intense public demand; I mean, it wasn’t going to help sell more records.

WOMACK: I think they were very aware that they were these kinds of contradictions, that they were talking out of both sides of their mouths. Their own actions hadn’t caught up with their intellectual abilities. But that’s true right now with the way people behave. But I do think they were conscious of the fact that they were hypocrites. I think it actually makes them more interesting that they’re both victimizers, to a certain extent, and wanting to be better. They are very fractured vessels, but they knew enough to believe it was important and to use their massive bully pulpit or bullhorn, which is still about the biggest one in history, to talk about these things.

The thing that they had that’s so important is they had the ability to not have to care. They were so influential, and they had such an enormous position and privilege, obviously, that they didn’t have to care about these kinds of things. They did them anyway because they felt they were important. And they probably had enough confidence to realize that they could take risks. They did something that still few artists do, at least in popular music, and that is, every time they’d make a new record, they’d sit down with [producer] George Martin, and they would say, “Let’s not make this record sound like the last one. Let’s sound different.” So you go from “Help!” to “Rubber Soul” to “Revolver” to “Sgt. Pepper” to the “White Album” to “Let It Be” to “Abbey Road.” Each one has a different base sound that they’re working on. That in itself is pretty risky. So they took risks because they were very much like the modernists in that way. That’s what you do: You keep pushing forward.

This interview has been edited for clarity and condensed for length.