“As a scholar of law, inequality, and the long Civil Rights movement, I am deeply interested in issues related to slavery and its legacy,” said Tomiko Brown-Nagin, who will lead the committee.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A renewed focus on slavery

New University-wide initiative will deepen the exploration of Harvard’s historical ties to enslavement

Harvard has been involved for years in the difficult task of exploring the University’s historical ties to slavery through a range of programming and scholarship supported by the Office of the President, by faculty, and by students across campus. Now, a new University-wide effort will be devoted to that work.

Harvard President Larry Bacow on Thursday announced creation of “Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery,” an interdisciplinary initiative that will build on the University’s earlier undertakings. In a letter to the Harvard community, Bacow cited the vital importance of continuing to engage with Harvard’s history, of creating cohesion and connections across the University around the issue, of bringing a wide range of voices and rigorous academic research into the conversation, and of developing programming to engage the community in discussion.

Bacow named Tomiko Brown-Nagin, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, to chair a University committee made up of faculty from across Harvard’s Schools and disciplines who will give shape and direction to the effort. Radcliffe will be the anchoring space for Harvard’s work in this area over the coming years.

“President Bacow has said that Harvard has a responsibility to use its immense resources, assets, ideas, and people to address difficult problems and painful divisions. I share these same ambitions for the work of Radcliffe,” said Brown-Nagin, who is also Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School, and professor of history in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

“It is entirely in keeping with our mission to focus on these issues. We need to articulate our values; we need to be at the forefront of research about inequality and remedies to inequality. What happens at Harvard matters. We are a leader in higher education, and we should be a leader more broadly — especially at this time when inequality and the lingering effects of slavery and Jim Crow [laws] are topics of public concern.”

Brown-Nagin said the task is consistent with Radcliffe’s newly announced strategic plan, “Radcliffe Engaged,” “whose overarching vision is to ensure that we are doing work that has public impact and supports applied research that engages with pressing issues. Certainly the study of slavery and its impact falls within that remit.”

In his letter, Bacow said the new initiative “will build on the important work undertaken thus far, provide greater structure and cohesion to a wide array of University efforts, and give additional dimension to our understanding of the impact of slavery. This work will allow us to continue to understand and address the enduring legacy of slavery within our University community.”

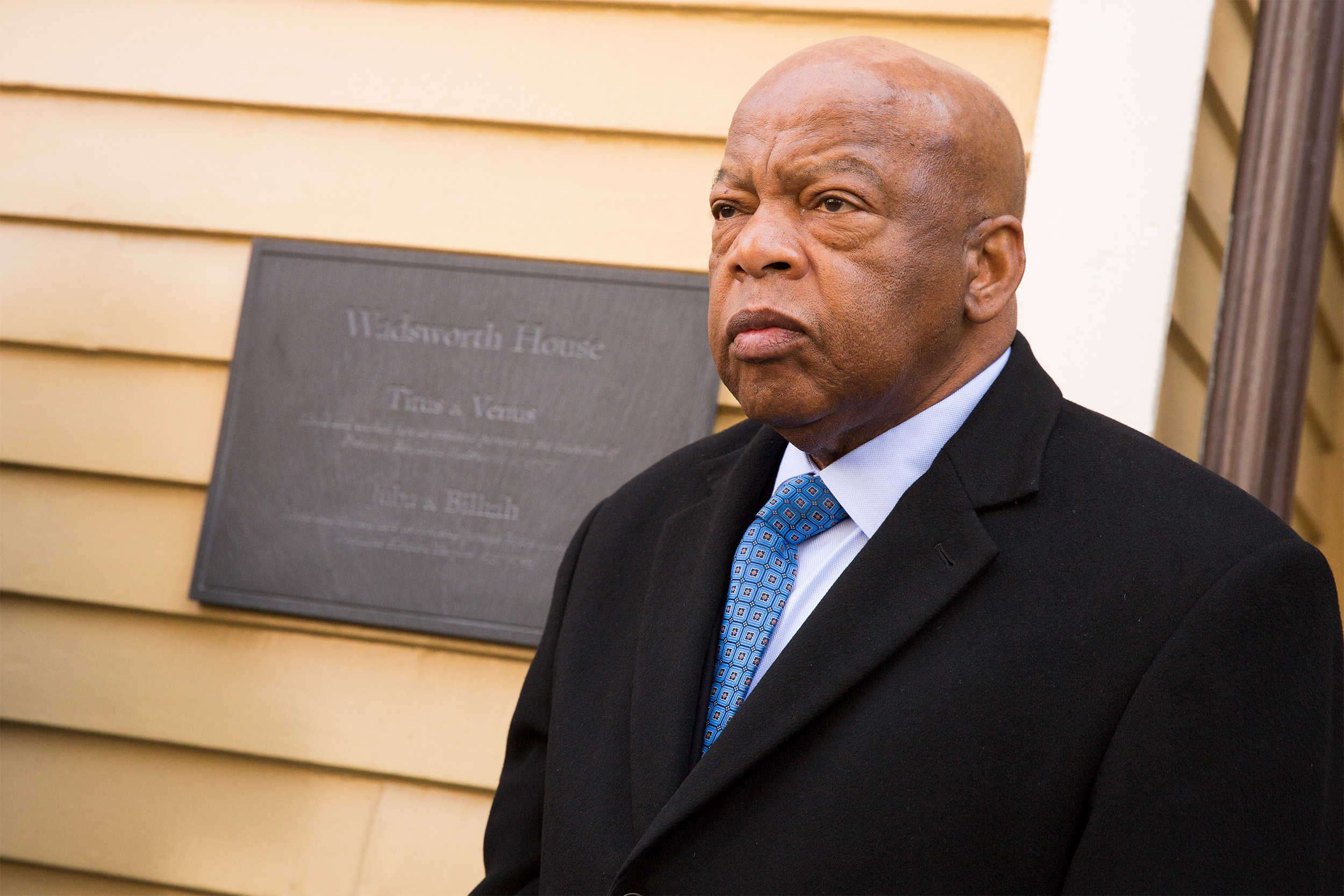

In April 2016, U.S. Rep. John Lewis unveiled a plaque at Wadsworth House in honor of four enslaved persons who lived and worked there in the 1700s.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

As Bacow said in his letter, Brown-Nagin acknowledged that such a difficult topic requires a range of a voices with expertise in myriad disciplines. The 12-person committee, she said, is perfectly suited to the task.

“This committee is a powerhouse. It includes scholars of great integrity who have dedicated their lives to thinking about inequality and its consequences,” she said. “We selected committee members from a broad range of disciplines and professional backgrounds. It includes leading scholars on slavery, medical anthropology, law, and more. I look forward to benefiting from their expertise and creativity as we work together to produce a set of recommendations for how to move forward; how to commemorate; and how to engage the public, the community, and students. This is deeply important work.”

Brown-Nagin called the initiative “a critical new chapter in an ongoing effort” begun by committee member Sven Beckert, Laird Bell Professor of History at the University.

In 2007, students in Beckert’s undergraduate course began investigating the University’s historical ties to slavery. Building on the findings, then-President Drew Faust convened a faculty panel in 2016 to explore those connections further. On April 16 of that year, Faust and U.S. Rep. John Lewis, a Civil Rights icon, unveiled a plaque on Wadsworth House in honor of Titus, Venus, Bilhah, and Juba, four enslaved persons who during the 1700s lived and labored in the households of two Harvard presidents.

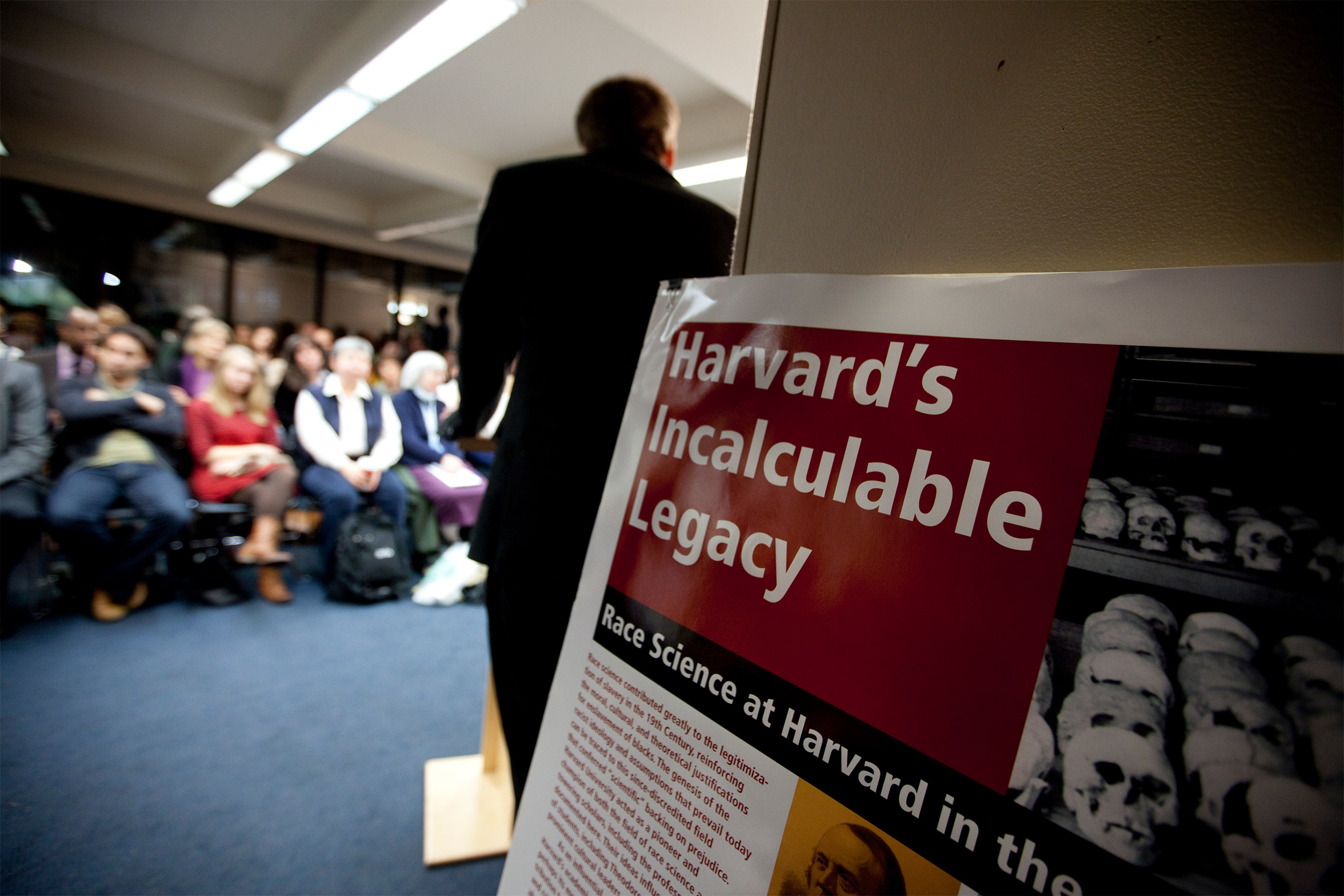

In 2017, Radcliffe hosted a daylong symposium with scholars from across campus and beyond that examined the relationship between slavery and universities. Speaking of Harvard’s history during the event, Faust said the School was complicit in slavery from the 17th century until the practice ended in Massachusetts in 1783, and that Harvard maintained financial and other ties to the slave-holding South through Emancipation during the Civil War.

“To acknowledge those realities is essential if we are to undermine the legacies of race and slavery that continue to divide our nation, and if we are to commit ourselves to building a better future,” said Faust.

Over the past several years, Harvard Law School also has been confronting its ties to slavery. In 2016, the Corporation approved the School’s recommendation to retire its shield because of its ties to slavery. Its design was modeled on the family shield of Isaac Royall Jr., whose bequest to the College in 1781 created the first endowed professorship of law at the College in 1815. Royall’s wealth came from the long labor of enslaved persons on his farms in Massachusetts and on his plantation on the island of Antigua. The following year, the Law School installed a plaque in the center of its plaza dedicated to the enslaved people whose work helped found the School.

In 2017, Ta-Nehisi Coates was among the scholars who spoke at Radcliffe’s daylong symposium that examined the relationship between slavery and universities. Students in Sven Beckert’s undergraduate course students investigated the University’s historical ties to slavery.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell, Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photos

“It is my hope that the work of this new initiative will help the University gain important insights about our past and the enduring legacy of slavery — while also providing an ongoing platform for our conversations about our present and our future as a University community committed to having our minds opened and improved by learning,” wrote Bacow.

The University’s efforts mirror those at other institutions that are coming to terms with their painful past. Harvard is part of Universities Studying Slavery, a growing consortium of schools and universities that are contemplating or already investigating their own histories involving slavery and racism. The group includes more than 50 institutions from the United States, Canada, Scotland, and England.

For Brown-Nagin, her new role aligns well with her academic interests.

“As a scholar of law, inequality, and the long Civil Rights movement, I am deeply interested in issues related to slavery and its legacy. My scholarship also grapples with educational access and opportunity, making this a genuinely exciting endeavor for me.”