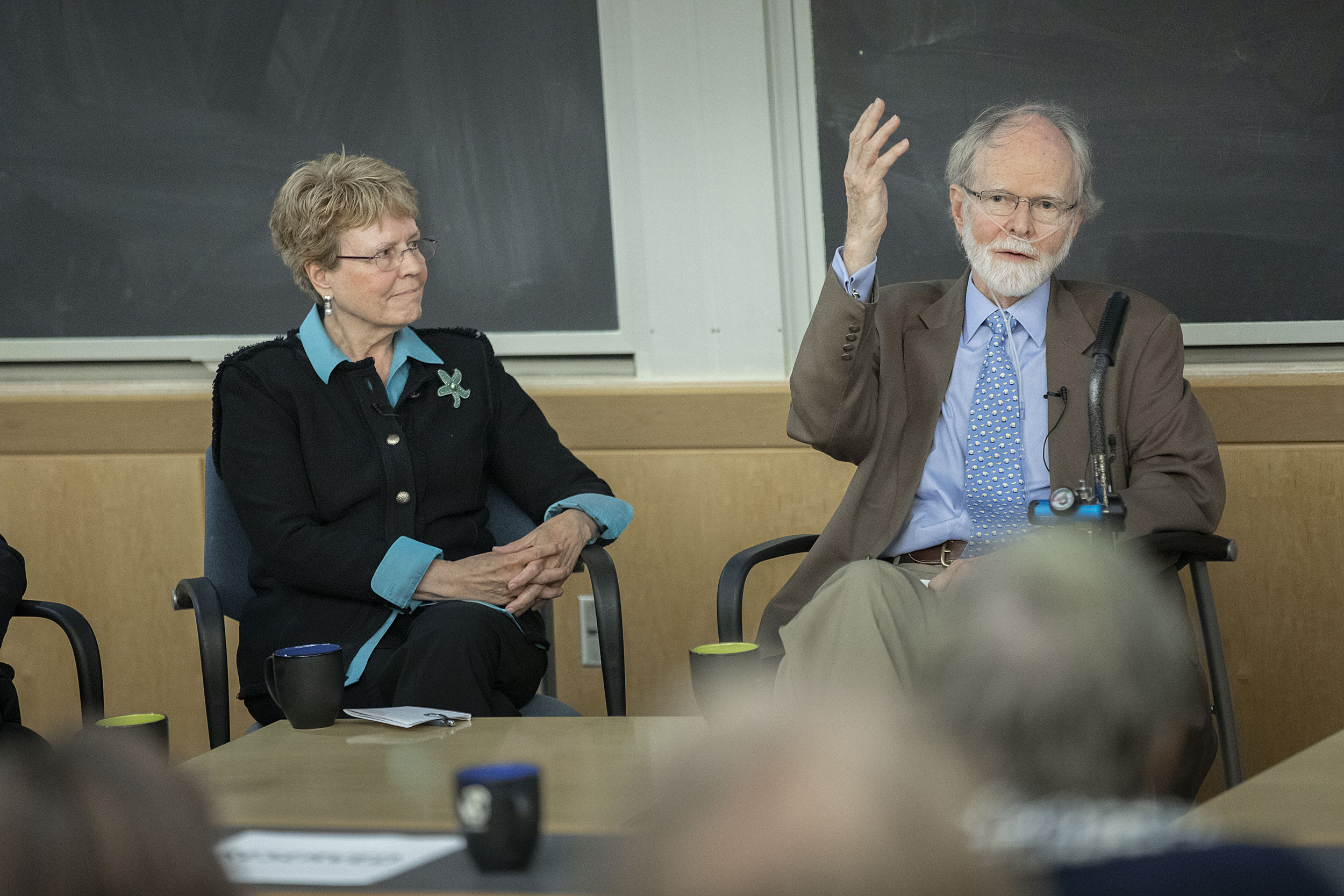

Jane Lubchenco (left) and Jim McCarthy discuss impact of climate change on Earth’s oceans.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Solve ocean’s troubles and climate change too?

Panel discussion honoring James McCarthy brings experts and innovative ideas to campus

As part of its coverage of Climate Week (Sept. 23-29), the Gazette is running a series of stories on the issues involved, while spotlighting areas of University involvement, including research and programs designed to make a difference. For more information, visit the Tackling Climate Change site.

The pollution, acidification, and warming plaguing the world’s oceans are often seen as intractable as climate change and as important to resolve. But Jane Lubchenco, former administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), offers a new perspective, saying we should look to the seas for solutions, not problems.

“Seventy-eight percent of countries border the ocean and, despite that, the oceans for the most part are not front and center when we think of mitigating climate change,” said Lubchenco.

The administrator of the NOAA during the Obama administration and now a professor at Oregon State University spoke at a Monday afternoon panel convened to honor the career of James McCarthy, the Alexander Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography who has been at Harvard for 45 years, conducting research on the oceans, and adding his voice to the environmental policy debate.

Despite the litany of problems facing the oceans, Lubchenco said, we should look to the opportunities they offer to solve both marine problems and those of global climate, opportunities which could help limit warming to 1.5 degrees Centigrade by 2100, the goal pursued by signatories to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

There are opportunities, Lubchenco said, to sequester carbon in coastal habitat by restoring mangrove forests, salt marshes, and sea grass beds, which, though disappearing, have the potential to store more carbon than land-based systems per unit area. That restoration, she said, will also make the seas healthier, boosting fisheries by protecting and creating habitat used as nurseries for juveniles of many species.

Similarly, she said, there are ways to reduce emissions from shipping and fishing activities, to take advantage of the ocean’s biological pump (which moves carbon to the sea floor as biological life dies and drifts downward), get renewable energy from the ocean itself, and to shift human diets toward seafood, which is less resource-intensive and healthier than land-based meat diets.

“The ocean, then, has a key role to play in both mitigation and adaptation,” Lubchenco said. “It is time to change our narrative around the ocean.”

Panelists Jeremy Jackson (from left), Jane Lunchenco, Jim McCarthy, Sallie Chilsholm, Bud His, and William Moomaw discuss climate change problems and potential solutions in front of a rapt audience.

McCarthy agreed.

“If I think about the future, I very much like the position that Jane advocates: We cannot ignore the ocean. It’s essential we think about the ocean in all these future plans,” McCarthy said. “I think the hopeful message is that it is something … that is absolutely essential.”

Daniel Schrag, Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment, which sponsored the event, said one of the great benefits of working at Harvard is great colleagues, and McCarthy, who served as a mentor to him, was one of his first and foremost.

“There are many days when I feel like the luckiest person in the world, and the reason is I have spectacular colleagues,” Schrag said. “I am incredibly fortunate to be part of this community … but Jim McCarthy is dear and special to me. My entire time at Harvard he has been a mentor and a steady presence.”

Several of the speakers reflected on shared experiences and the impact McCarthy had on their careers, providing a nudge that landed one at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and another in the top chair at the New England Aquarium. McCarthy, who sat on a panel during the event’s second half, said he was “extremely honored” by the gathering and said in reviewing the list of speakers, it was clear that each felt an obligation to not only conduct science, but a responsibility to communicate what they found to policymakers. McCarthy himself chaired a working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2001 report and served in leadership positions, among others, for the Union of Concerned Scientists and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Other speakers addressed an array of ocean-centric topics, but in each case highlighted existing opportunities to engage with the problems of today. Overfishing, which is rampant in the world’s oceans, can be addressed by effective regulation. Aquaculture has the promise of boosting the availability of seafood even as free-swimming stocks decline. Even something as difficult as coral bleaching, a phenomenon prompted by warmer than normal water that has some predicting the doom of the world’s reefs, has been shown to be less deadly on reefs that are otherwise healthy and protected from pollution and overfishing, according to Jeremy Jackson of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

“There’s a really dangerous arrogance to the notion of hopelessness,” Jackson said. “Total hopelessness assumes that we know everything there is to know. … When we think we know everything, we preclude opportunity.”