Love stinks

“A Gingerbread Cookie,” from the Museum of Broken Relationships.

Photo by Ana Opalić

In advance of her Harvard appearance, Leslie Jamison ’04 explores loss and renewal during a visit to the Museum of Broken Relationships in this excerpt from her new nonfiction collection

The Museum of Broken Relationships is a collection of ordinary objects hung on walls, tucked under glass, backlit on pedestals: a toaster, a child’s pedal car, a handmade modem. A toilet-paper dispenser. A positive pregnancy stick. A positive drug test. A weathered ax. They come from Taipei, from Slovenia, from Colorado, from Manila. All donated, each accompanied by a story: In the 14 days of her holiday, every day I axed one piece of her furniture.

One of the most popular items in the gift shop is the “Bad Memories Eraser,” an actual eraser sold in several shades. But in truth the museum is something closer to the psychic opposite of an eraser. Every object insists that something was, rather than trying to make it disappear. Donating an object to the museum permits surrender and permanence at once: you get it out of your home, and you make it immortal. She was a regional buyer for a grocer and that meant I got to try some great samples, reads the caption next to a box of maple-and-sea-salt popcorn. I miss her, her dog, and the samples, and can’t stand to have this fancy microwave popcorn in my house. The donor couldn’t stand to have it, but he also couldn’t bear to throw it away. He wanted to put it on a pedestal instead, honor it as the artifact of an ended era.

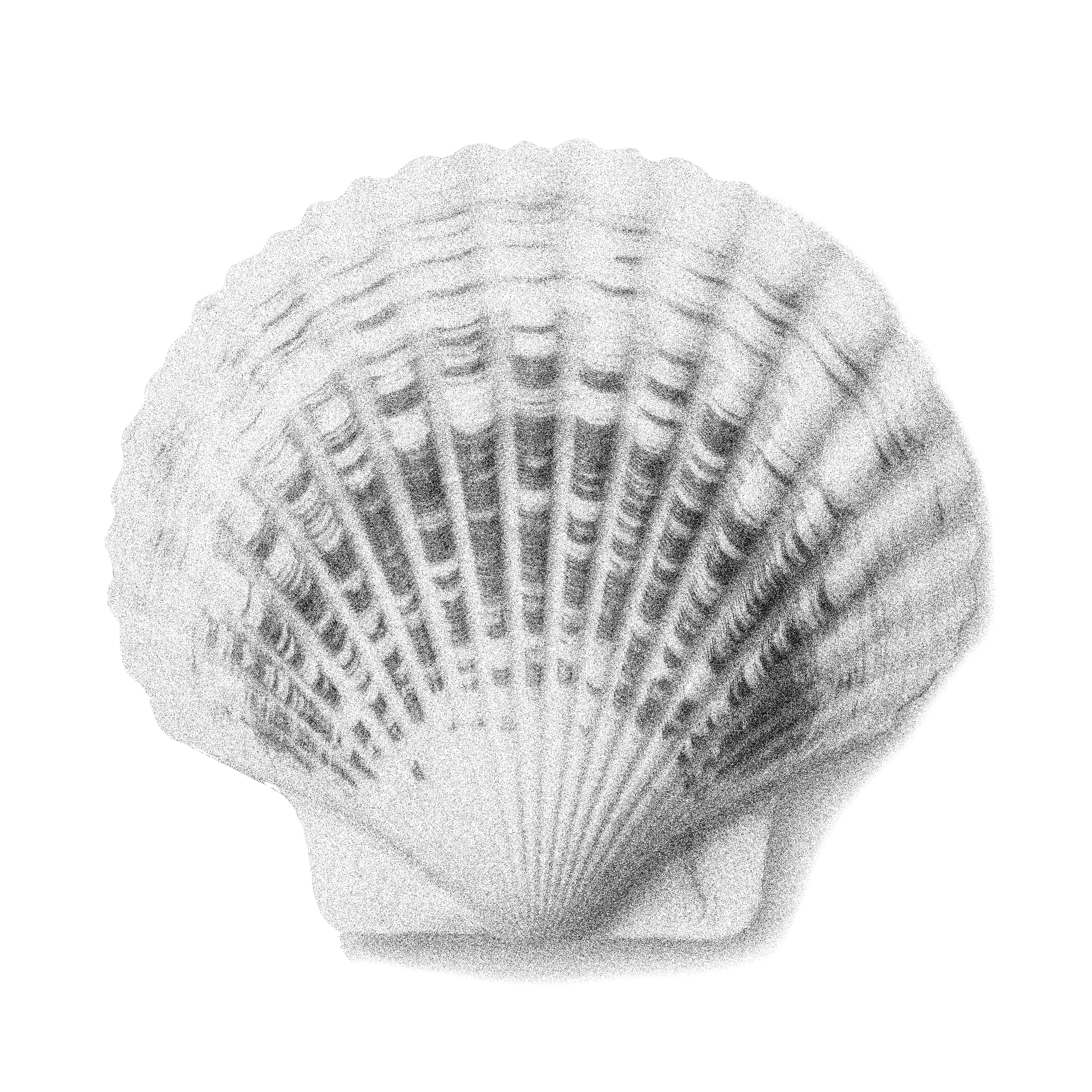

Exhibit 1: Clamshell Necklace

Florence, Italy

It’s a simple necklace: a tiny, brown-striped clamshell tied to a black leather cord. The shell was gathered from a beach in Italy and attached to the cord by means of two holes drilled into the shell with a dental drill. The person who made the necklace for me was a dental student in Florence at the time. He did it secretly, in one of his classes, while he was supposed to be learning how to make crowns. I wore that necklace every single day, until I didn’t anymore.

When I visited the museum in Zagreb, Croatia — where it occupies a baroque aristocratic home perched at the edge of Upper Town — I was two and a half years married, two months pregnant, and traveling on my own. Almost everyone else had come as part of a couple. The lobby was full of men waiting for wives and girlfriends who were spending longer with the exhibits. I imagined all these couples steeped in schadenfreude and fear: “This isn’t us. This could be us.” In the guest book, I saw one entry that said simply: “I should end my relationship, but I probably won’t,” and fingered my own wedding ring — as proof, for comfort — but couldn’t help imagining the ring as another exhibit, too.

Before flying to Zagreb, I’d put out a call to my friends — What object would you donate to this museum? — and got descriptions I couldn’t have imagined: a clamshell drilled by a dental student, a shopping list, four black dresses, a single human hair, a mango candle, a penis-shaped gourd.

The objects my friends described all reached toward obsolete past tenses: that time we dreamed the same dream. The objects were relics from those dreams, as the museum exhibits were relics from the dreams of strangers — attempts to insist that these dreams had left some residue behind.

Walking through the museum felt less like voyeurism and more like collaboration. Strangers wanted their lives witnessed, and other strangers wanted to witness them. The curatorial notes quoted Roland Barthes: “Every passion, ultimately, has its spectator … [there is] no amorous oblation without a final theatre.” There was a democratic vibe to the place. Its premise implied that anyone’s story was worth telling, and worth listening to.

Exhibit 2: Shopping List

Princeton, N.J.

I spent the first seven years of my twenties in serious long-term romantic relationships, and then I got my heart broken when I was 27 and never dated again. Ten years into my singleness, having moved four times since my last breakup, gotten a Ph.D. and a job, gained 40 pounds, I was going through a box of old too-small summer clothes and slipped my hand into the back pocket of some abbreviated jean shorts and felt a scrap of paper which turned out to be a shopping list in my heartbreaking ex’s handwriting: “batteries, lg. black trash bags, Tide (small) bleach alt., lg. onion.” I suddenly remembered his gratuitous use of periods — oddly, always after he signed his name, every email and every letter ending with a punctuation mark of finality.

The Museum of Broken Relationships began with a breakup. Back in 2003, after Olinka Vištica and Dražen Grubišić ended their relationship, they found themselves in the midst of a series of difficult conversations about how to divide their possessions. As Olinka put it: “The feeling of loss … represented the only thing left for us to share.” Over the kitchen table one night, they imagined an exhibit composed of all the detritus from breakups like their own, and when they finally created this exhibition — three years later — its first object was one salvaged from their own home: the mechanical windup rabbit they’d called Honey Bunny.

Just over a decade later, the story of their breakup has become the museum’s myth of origins. “It was the strangest thing,” Olinka told me over coffee one morning. “The other day I was getting out of my car, right outside the museum, and I heard a tour guide telling a group of tourists about the bunny. He said: ‘It all started with a joke!’” Olinka wanted to tell the tour guide it hadn’t been a joke at all, that those early conversations had been deeply painful, but she realized that the story of her own breakup had become a public possession, subject to the retellings and interpretations of others. People took whatever they needed from it.

When Olinka and Dražen finally found a permanent home for their exhibition, the space was in terrible shape: the first floor of an eighteenth-century palace in utter disrepair, perched near the top of a funicular railway. “We were a little bit crazy,” Olinka told me. “We had tunnel vision. Like when you fall in love.” Dražen finished the floors and painted the walls, restored the brick arches. He did such a great job that people kept asking Olinka: “Are you sure you wanted to break up with this guy?”

That’s the pleasing irony of the museum’s premise: that in creating a museum from their breakup, Olinka and Dražen ended up forming an enduring partnership. From the museum coffee shop, the mechanical bunny was visible in its glass case — a presiding mascot and a patron saint. “People think that the bunny is our object,” Olinka told me. “But really the museum is our object. Everything that it’s become.”

Exhibit 3: A copy of ‘Walden’ by Henry David Thoreau

Bucharest, Romania

R. and I both started reading “Walden” in the beginning of our relationship. It takes a certain amount of solitude to grow fond of “Walden,” and our relationship was a vessel where we could put both our isolations while keeping them separate, like water and oil. We were living together, but decided to sleep in different rooms, both reading “Walden” before falling asleep. It was our proxy: our bodies were separated by the wall in between our rooms, but our minds were converging towards the same ideas. By the time we broke up, neither of us had finished. Nevertheless, we continued reading it.

These ordinary objects understood that a breakup is powerful because it saturates the banality of daily life, just as the relationship itself did: every errand, every annoying alarm-clock chirp, every late-night Netflix binge. Once love is gone, it’s gone everywhere. It’s a ghost suffusing daily life just as powerfully in its absence. A man leaves his shopping lists scattered across your days, cluttered with personality tics and gratuitous periods, poignant in their specificity: “lg. black trash bags” summoning that time the trash bags were too small, or “lg. onion,” the type necessary for a particular fish stew prepared on a particular humid summer evening.

Exhibit 4: Envelope with Single Human Hair

Karviná, Czech Republic

In 1993 I graduated college and taught English for a year in a coal mining village on the Polish/Czech border, a depressed, polluted, communist city in which I experienced loneliness like I’d never known before or since. The summer before I left, I met a Scottish boy named Colin at the amusement park in Salisbury Beach where he was running the Ferris wheel. After the summer, we wrote letters to each other, and sometimes a letter from him was the only thing that got me through my day. He had auburn curls I adored and once when the familiar airmail-blue envelope arrived in my box I saw he had taped the flap and a single piece of his curly hair got trapped under the tape: a part of his body, his DNA, that would one day be shared with our children. After he dumped me in a pretty cowardly way — just stopped writing — I still checked my box every day and wept, then returned to my sad communist flat and wept, then looked at the envelope that held his single curly hair and wept some more.

“The museum has always been two steps ahead of us,” Olinka told me, explaining that it’s had a will of its own from the start, an impulse to exist beyond her and Dražen. In the decade after their first exhibition, the museum took many shapes: permanent installations in Zagreb and Los Angeles, a virtual museum comprising thousands of photographs and stories, and forty-six pop-up installations all over the world — from Buenos Aires to Boise, Singapore to Istanbul, Cape Town to South Korea, from the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam’s red-light district to the European Parliament in Brussels, all locally sourced, like an artisanal grocer, stocked with regional heartbreak.

Exhibit 5: Four Black Dresses

Brooklyn, N.Y.

I would donate to the museum the four black dresses hanging in my closet: a shirtwaist, a sundress, a ribbed turtleneck, and an A-line of raw silk. Two of these dresses were given to me by my ex, and two I bought myself, but they all date from a time in my life when I imagined I could become the person I wanted to be by adopting a uniform. I thought — we both thought — that the problem of my un-femininity, my lack of interest in clothes, my general un-hipness, could be solved by my becoming one of those literary party regulars who dresses in black, makes cutting comments, and writes bestsellers. Two months before we broke up, this man said to me, “I’m just waiting to see if you become famous, because then I think I might fall in love with you.” A horrible thing to say, clumsy in its attempt at honesty — yet I did see how this was what, on some level, I’d been promising him, the fantasy of a public self we’d been co-constructing. I would donate these dresses to the museum — except that I still wear them. All the time. It’s just that I wear other dresses — purple, floral, geometric, pink — as well.

I grew up in a family thick with divorces and overpopulated by remarriages: both sets of grandparents divorced, my mother’s twice; both my parents married three times; my oldest brother divorced by forty. Divorce seemed less like an aberration than an inevitable stage in the life cycle of any love.

But in my family the ghosts of prior partners were rarely vengeful or embittered. My mother’s first husband was a lanky hippie with the kindest eyes who once brought me a dream catcher. My beloved aunt’s first husband was an artist who made masks from the dried palm fronds he gathered on beaches. These men enchanted me because they carried with them not only the residue of who my mom and aunt had been before I knew them, but also the spectral possibilities of who they might have become.

Which is all to say: I grew up believing that relationships would probably end, but I also grew up with the firm belief that even after a relationship was over, it was still a part of you, and that this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. When I asked my mother what object she would contribute to the museum, she chose a shirt she had bought in San Francisco, years before I was born, with the woman she had loved before she met my father.

The gospel of serial monogamy could have you believe that every relationship was an imperfect trial run, useful only as preparation for the relationship that finally stuck. In this model, a family full of divorces was a family full of failure. But I grew up seeing them as something else, grew up seeing every self as an accumulation of its loves, like a Russian nesting doll that held all of those relationships inside.

Exhibit 6: Plastic Bag of Pistachio Nuts

Iowa City

Dave and I spent four years together. I loved Dave with all of myself, like a wet cloth wrung out. In the first apartment we shared — once things had deteriorated and we were fighting frequently — we started to notice these gray moths flitting clumsily around our kitchen. When we smashed them against the walls, their innards left silvery trails against the pale paint. We kept killing them, kept fighting, kept hoping that if we killed enough moths, if we had enough fights, then eventually we’d get rid of them for good. After several months, we discovered where the moths were coming from: a plastic bag in the pantry full of old pistachios, thick with the white webbing of their tiny eggs. We threw it out. I kept hoping we’d discover our equivalent of that bag — the core of all our fights, their primal source — so we could banish it.

My breakup with Dave, at the end of my twenties, mattered more than any other breakup ever had, and lasted longer — the loss itself, and its aftermath. Dave and I had spent much of our relationship trying to figure out if our relationship could work, and I thought that breaking up would liberate us from that pull-and-tug. It didn’t. We broke up, got back together, broke up again, then talked about getting married. Our split became my partner the way Dave had been my partner. There was an absence that held his shape, and it followed me everywhere.

Exhibit 7: Bottle of Crystal Pepsi

Queens, N.Y.

After the end of my relationship with the man I thought I would marry, I met an unexpectedly wonderful lawyer who lived in Queens. He took me to trivia night at his local bar in Astoria. He took me to a Christmas party at his law office near Times Square. He took me to the Blazer Pub, near his childhood home upstate, where we ate burgers and played shuffle bowling. I knew he wasn’t “the one” but also suspected I no longer believed in “the one” — not because I’d never met him, but because I had and now we were done. The lawyer made me laugh. He made me feel comfortable. We ate comfort food. We made pancakes with raspberries and white chocolate chips and watched movies on weekend mornings. He found old reruns of “Legends of the Hidden Temple,” the stupid game show we’d both loved as kids, and gave me a ten-year-old bottle of Crystal Pepsi he’d found online — my favorite soda when I was young, discontinued for years. He was remarkable, but I couldn’t ever quite see him — or see that — because I never really believed in us. Nothing about us made me feel challenged. His devotion started to feel like a kind of claustrophobia. It was like he taught me how much I struggled to live inside love — to understand something as love — without difficulty.

In many ways, that relationship was another chapter in the unfolding story of my relationship with Dave, part of its epilogue. When the lawyer and I broke up, it felt less like a fresh sadness and more like a return to the sadness that was already there, missing the one I’d been missing all along. A few months later, I met the man I would marry.

Before I left for Croatia, I thought of bringing the bottle of Crystal Pepsi the lawyer had given me, to donate to the museum as a memento of my last breakup before marriage. But I never put it in my luggage. Why did I want to keep it at home, on my bookshelf? It had something to do with wanting to acknowledge the man who’d given it to me, because I hadn’t given him enough credit while we were together. Keeping his last gift was a way of granting him credit in the aftermath.

If I’m honest with myself, keeping that bottle of Crystal Pepsi isn’t just about honoring the man who gave it to me, or what we shared. It also has to do with enjoying that glimpse of sadness and dissolution, with holding on to some reminder of the pure, riveting feeling of being broken. These days my life is less about the sublime state of solitary sadness or fractured heartbreak and more about waking up each day and making sure I show up to my commitments. My days in Zagreb were about Skyping with my husband and emailing a good-morning video to my stepdaughter. They were about feeding the fetus inside me: Istrian fuzi with truffles, noodles in thick cream; sea bream with artichokes; something called a domestic pie; something called a vitamins salad.

Life now is less about the electricity of thresholds and more about continuance, coming back and muddling through; less about the grand drama of ending and more about the daily work of salvage and sustenance. I keep the Crystal Pepsi because it’s a souvenir from the fifteen years between my first breakup and my last that I spent in a cycle of beginnings and endings, each one an opportunity for self-discovery and reinvention and transformative emotion; a way to feel infinite in the variety of possible selves that could come into being. I keep the Crystal Pepsi because I want some reminder of a self that felt volcanic and volatile — bursting into bliss, or into tears — and because I want to keep some proof of all the unlived lives, the ones that could have been.

Jamison will be appearing in conversation with James Wood, critic and professor of the practice of literary criticism, Tuesday at 6 p.m. at Fong Auditorium at the Mahindra Humanities Center. Excerpt from “Make it Scream, Make it Burn” by Leslie Jamison. Copyright © 2019 by Leslie Jamison. Available from Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group Inc.